Friday

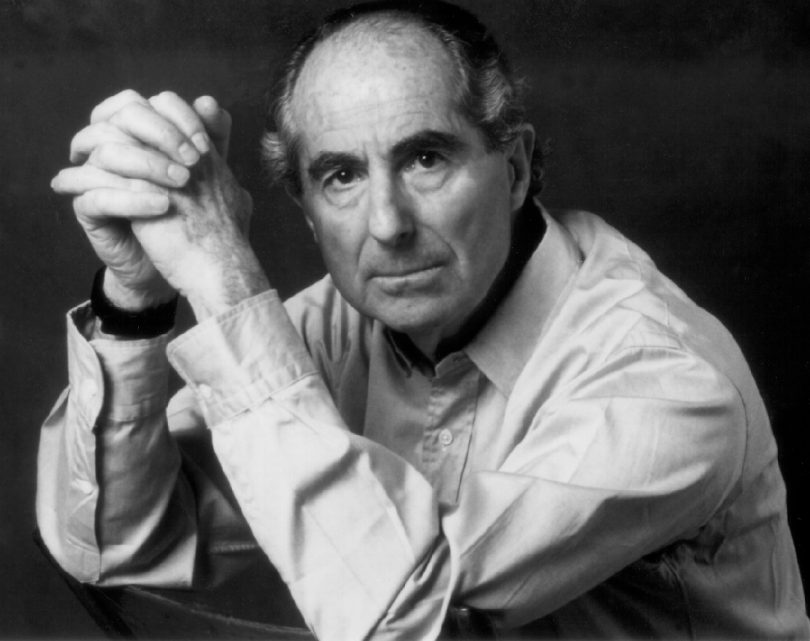

I feel that I am insufficiently acquainted with Philip Roth, who died last week. I first encountered him, believe it or not, in Sports Illustrated, which I read religiously as a teenager and therefore encountered an excerpt from the little discussed Great American Novel. It’s about a professional baseball league that is so corrupt that eventually all memory of it is expunged from the history books. In its heyday, however, it featured (so an unreliable narrator contends) a host of colorful characters, including the wonderfully named rookie pitching sensation Gil Gamesh.

In his greatest game, Gamesh pitches 80 straight strikes—none of them fouled off—so that he is one pitch shy of the most perfect of perfect games. The umpire calls the 81st pitch a ball, however, and the 82nd pitch takes out his larynx. Gamesh is banished from baseball for life and wanders the world in exile, sometimes (so legend has it) playing in pick-up games.

I wasn’t sure that I liked Great American Novel, but I was enthralled with the characters, especially a baseball team made of such misfits as two dwarfs (good at drawing walks), a one-armed player, and a kleptomaniac pitcher who keeps stealing the balls. Or so I vaguely remember.

I was a reserved and reticent child and Roth’s over-the-top imagination, featuring narrators who push again the bounds of sanity, was a revelation to me. I don’t know whether I could have handled Portnoy’s Complaint, which I read decades later and which would have exacerbated all my anxieties about sexuality. But Roth’s baseball novel showed me that literature could be an uncontainable force and was therefore something to be taken seriously.

My favorite Roth novel is The Human Stain, in large part because, when I first read it, it kept surprising me. Each time I thought was becoming a tiresome attack on political correctness, it upended my expectations.

Human Stain taught me that human beings are always more complex than the boxes we put them in. Our judgments invariably fail to do people justice. In the novel, a college professor uses the word “spooks” in class and is accused of racism by African American students. The incident seems like an example of political correctness run amuck, but the story becomes more complex.

It turns out that the professor is himself African American and has been passing for white all of his life. Thus, if he doesn’t handle the situation well, it’s in part become he is antagonistic towards his own race. It’s agonizing to see him break his mother’s heart, denying his race and his relationship to her so that he can “take the future into his own hands rather than to leave it to an unenlightened society to determine his fate.”

The novel provides insight into the lynching described in Maya Gittelman’s The Family Tree: A Lynching in Georgia, a Legacy of Secrets, and My Search for the Truth (2016), which I’ve just encountered. In that book, a reporter learns that she had relatives on both sides of the lynching of four innocent African Americans in 1912—which means that there those with African American blood among the mob. Anxieties over being exposed and the need to deny may well have contributed to some of the ferocity. Roth captures how deeply race enters and complicates American identity.

Human Stain also has the most vivid description of PTSD that I have ever encountered. After reading it, no one can ever take the illness lightly again.

Retirement will give me a chance to read other Roth novels that I’ve been hearing about for years, especially American Pastoral. It’s slowly dawning on me is that my time for such reading has expanded exponentially.