Spiritual Sunday

A couple of Sundays ago I heard a sensitive sermon about restlessness. Reflecting upon the crowds that follow Jesus after the miracle of the loaves and the fishes (John 6:24-35), Rev. John Runkle quoted St. Augustine’s prayer about a restless heart.

Two authors who write about restlessness instantly came to mind: George Herbert in his poem “The Pulley” and Charlotte Bronte in Jane Eyre. Associating St. John, Augustine, Herbert and Bronte leads to some interesting insights into this spiritual condition.

In the passage from John, Jesus tells the crowds that have followed him,

Very truly, I tell you, you are looking for me, not because you saw signs, but because you ate your fill of the loaves. Do not work for the food that perishes, but for the food that endures for eternal life, which the Son of Man will give you. For it is on him that God the Father has set his seal.

And further on:

I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty.

Rev. Runkle detected a spiritual restlessness in the crowds, prompted by a longing for contact with the divine. St. Augustine, he noted, captures that hunger in his well-known short prayer, “Thou hast made us for thyself, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in thee.” Rev. Runkle’s sermon examined how, to address that restlessness, we sometimes turn to superficial remedies.

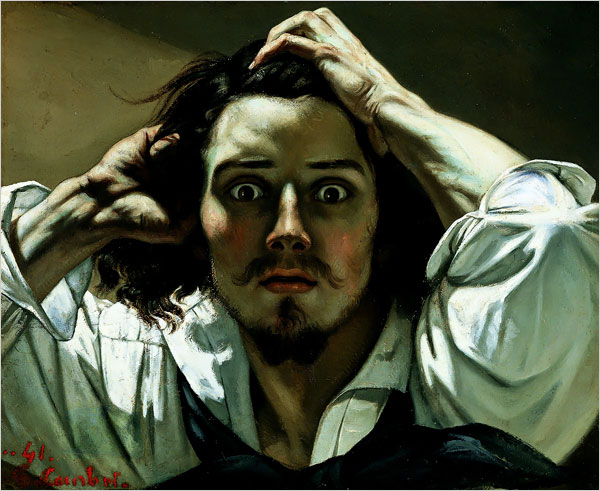

In “The Pulley,” which I’ve written about here and mentioned here, Herbert describes restlessness as intrinsic to the human condition, and it certainly shows up in many, perhaps most, of his poems. He also comes up with a novel explanation for it. God made us restless, he says, in order that we will find our way back to Him. If we weren’t restless but were perfectly content, we would remain satisfied with our lives as they are. Our restlessness prods us to reach beyond ourselves and find God.

When God at first made man,

Having a glass of blessings standing by,

“Let us,” said he, “pour on him all we can.

Let the world’s riches, which dispersèd lie,

Contract into a span.”

So strength first made a way;

Then beauty flowed, then wisdom, honour, pleasure.

When almost all was out, God made a stay,

Perceiving that, alone of all his treasure,

Rest in the bottom lay.

“For if I should,” said he,

“Bestow this jewel also on my creature,

He would adore my gifts instead of me,

And rest in Nature, not the God of Nature;

So both should losers be.

“Yet let him keep the rest,

But keep them with repining restlessness;

Let him be rich and weary, that at least,

If goodness lead him not, yet weariness

May toss him to my breast.”

In my post on the poem, I talk about how “The Pulley” was Manhattan Project director Robert Oppenheimer’s favorite poem. Oppenheimer, brilliant and ambitious, was very familiar with restlessness. As a mathematician and physicist, he probably also appreciated the metaphor: as we are pulled down, we are in the same action pulled up.

I’ve written about Jane’s restlessness in the past but I want to take a slightly different tack here. Jane is not only restless because she envies male freedom, although that’s certainly one reason. She also wants spiritual sustenance.

She realizes that she would be spiritually sustained by living with Rochester in what she regards a life of sin. She quotes the terrifying passage from Matthew 5:29-30 to bolster her decision to leave, saying

No; you shall tear yourself away, none shall help you: you shall yourself pluck out your right eye; yourself cut off your right hand: your heart shall be the victim, and you the priest to transfix it.

The original passage is,

And if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell. And if thy right hand offend thee, cut it off, and cast it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell.

For a while, Jane thinks that she will overcome her restlessness and fulfill her spiritual destiny by going to India as a missionary. If Rochester stands in for her sensual side, then St. John is her austere disciplined side.

What she comes to realize, however, is that throwing herself into a cold, self-denying religion is no more a cure for spiritual restlessness than sensual gratification that ignores religion. By the end of the novel, she is able to honor both her earthly and her heavenly longings. She no longer worships Rochester as an idol but has entered into spiritual communion with him.

Thoreau famously wrote, “Most men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them.” Healthy religion provides guidance for how to nourish our deep hunger.

One Trackback

[…] Herbert and Bronte on Spiritual Restlessness […]