There is much about the sudden rise of ISIS that we do not understand. Today, following the lead of New York Times columnist Roger Cohen, I am offering a Dostoevskyan explanation, but that’s because nothing else seems to make any sense.

Before turning to it, however, we must acknowledge what a strange phenomenon ISIS is. A superb article in The New York Review of Books, authored anonymously, systematically shows the limitations of every conventional explanation. After surveying recent books on ISIS, it observes

Nothing since the triumph of the Vandals in Roman North Africa has seemed so sudden, incomprehensible, and difficult to reverse as the rise of ISIS. None of our analysts, soldiers, diplomats, intelligence officers, politicians, or journalists has yet produced an explanation rich enough—even in hindsight—to have predicted the movement’s rise.

The author adds that we arrive at theories and concepts to convince ourselves that we have a grasp on the situation but that “we should admit that we are not only horrified but baffled.”

Cohen too is baffled by ISIS, especially its recruiting success. “What leads young European Muslims in the thousands,” he asks,

to give up lives in France, Britain or Germany, enlist in the ranks of the movement calling itself the Islamic State, and dedicate themselves to the unlikely aim of establishing a caliphate backed by digital propaganda?

Cohen could add the United States to that list after the news that a couple from Mississippi State were arrested three days ago for planning to join ISIS.

The Times writer has a theory, however. After noting that ISIS offers “to give meaning, whether in this life or the next,” to disaffected young people, Cohen then mentions that these youths may yearn “to be released from the burden of freedom.”

Back in the 1939, German psychologist and social theorist Erich Fromm wrote a book called Escape from Freedom to explain the rise of Nazism. His idea that freedom may be experienced as a burden can be traced back to French existentialists like Camus and Sartre and, before them, to the Grand Inquisitor chapter in The Brothers Karamazov. I’ll touch on that in a moment but first here’s Cohen:

Western societies have been going ever further in freeing their citizens’ choices — in releasing them from ties of tradition or religion, in allowing people to marry whom they want and divorce as often as they want, have sex with whom they want, die when they want and generally do what they want. There are few, if any, moral boundaries left.

In this context, radical Islam offers salvation, or at least purpose, in the form of a life whose moral parameters are strictly set, whose daily habits are prescribed, whose satisfaction of everyday needs is assured and whose rejection of freedom is unequivocal. By taking away freedom, the Islamic State lifts a psychological weight on its young followers adrift on the margins of European society.

Cohen illustrates his point by pointing to the French novel Submission, by Michel Houellebecq, which is about a literature professor who becomes disaffected with Western values and converts to Islam. Quoting reviewer Mark Lilla, Cohen writes,

Houellebecq sees France in the grip of “a crisis that was set off two centuries ago when Europeans made a wager on history: that the more they extended human freedom, the happier they would be. For him, that wager has been lost. And so the continent is adrift and susceptible to a much older temptation, to submit to those claiming to speak for God.”

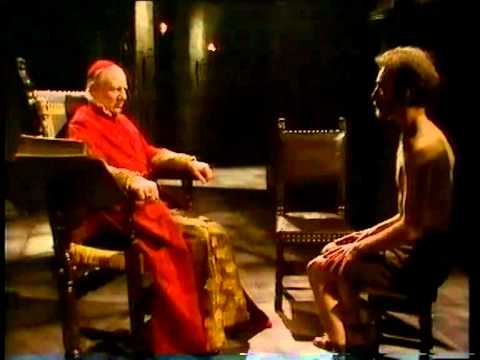

This sounds straight out of Nicholas Karamazov’s story of the Grand Inquisitor’s diatribe to Jesus, who has returned during to earth during the Spanish Inquisition.

The Inquisitor informs Christ that his aspirations for humanity were too high. When he rejected Satan’s temptations in the desert, he deprived people of what they really want. While Christ desired people to find God within themselves, what people really want is for someone to direct them. They crave “miracle, mystery, and authority.” People may be “more persuaded than ever that they have perfect freedom,” the Grand Inquisitor says, “yet they have brought their freedom to us and laid it humbly at our feet.”

The Inquisitor claims that the Inquisition and the Church “have vanquished freedom and have done so to make men happy. He explains,

“[F]or the first time it has become possible to think of the happiness of men. Man was created a rebel; and how can rebels be happy? Thou wast warned…“Thou hast had no lack of admonitions and warnings, but Thou didst not listen to those warnings; Thou didst reject the only way by which men might be made happy. But, fortunately, departing Thou didst hand on the work to us. Thou hast promised, Thou hast established by Thy word, Thou hast given to us the right to bind and to unbind, and now, of course, Thou canst not think of taking it away. Why, then, hast Thou come to hinder us?”

And further on:

Instead of taking men’s freedom from them, Thou didst make it greater than ever! Didst Thou forget that man prefers peace, and even death, to freedom of choice in the knowledge of good and evil? Nothing is more seductive for man than his freedom of conscience, but nothing is a greater cause of suffering. And behold, instead of giving a firm foundation for setting the conscience of man at rest for ever, Thou didst choose all that is exceptional, vague and enigmatic; Thou didst choose what was utterly beyond the strength of men, acting as though Thou didst not love them at all—Thou who didst come to give Thy life for them! Instead of taking possession of men’s freedom, Thou didst increase it, and burdened the spiritual kingdom of mankind with its sufferings forever. Thou didst desire man’s free love, that he should follow Thee freely, enticed and taken captive by Thee. In place of the rigid ancient law, man must hereafter with free heart decide for himself what is good and what is evil, having only Thy image before him as his guide. But didst Thou not know that he would at last reject even Thy image and Thy truth, if he is weighed down with the fearful burden of free choice? They will cry aloud at last that the truth is not in Thee, for they could not have been left in greater confusion and suffering than Thou hast caused, laying upon them so many cares and unanswerable problems.

There is much more—I urge you to go read the entire chapter—but here’s one last passage that seems to get at how ISIS seduces people:

Freedom, free thought and science, will lead them into such straits and will bring them face to face with such marvels and insoluble mysteries, that some of them, the fierce and rebellious, will destroy themselves, others, rebellious but weak, will destroy one another, while the rest, weak and unhappy, will crawl fawning to our feet and whine to us: “Yes, you were right, you alone possess His mystery, and we come back to you, save us from ourselves!”

In the tale’s shocking conclusion, the Grand Inquisitor prepares to crucify Christ a second time:

Thou shalt see that obedient flock who at a sign from me will hasten to heap up the hot cinders about the pile on which I shall burn Thee for coming to hinder us. For if any one has ever deserved our fires, it is Thou. To-morrow I shall burn Thee. Dixi.

ISIS’s own mass executions make this the Grand Inquisitor passage chillingly relevant.

If Cohen is right, then ISIS is a challenge to liberalism generally, not just to the Middle East or to the West. When we who are progressives advocate for more freedom, we assume that it will liberate the human spirit and lead to more justice and equality. Dostoevsky, however, warns of a backlash and, essentially, the rise of a new authoritarianism to which many will willingly submit.

One Trackback

[…] For fiction that challenges such utopian thinking, Douthat recommends Michel Houellebecq’s dystopian novels, The Elementary Particles (1998) and Submission (2015): […]