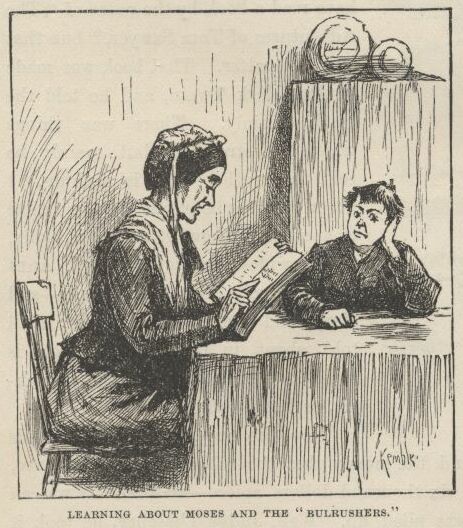

Many readers of Huckleberry Finn enjoy laughing at Miss Watson’s approach to teaching Huck. She tries to use the Bible to scare him into good behavior, insists that he sit still, and prohibits him from smoking and drinking. Romantics that we are, we make fun of her educational philosophy and find her a hypocrite, especially since she later considers selling Jim (!).

The fact that Huck internalizes some of her values makes it even worse. In the novel’s famous moment of decision, Miss Watson is enough in Huck’s head that he considers informing her of Jim’s capture. Then heart wins out over social conscience and he decides to rescue Jim instead, even though it means (so he thinks) that he will go to hell.

I never expected to see Miss Watson defended. But some minority students did so recently, thereby reaffirming my experience that, no matter how many times I teach a classic, students will always surprise me.

The occasion was a special summer session we conducted for in-coming “students from underrepresented groups.” A number of them are from challenging urban high schools. Some are white, some minority, some immigrant. Often they are the first people in their families to have attended college. As a public liberal arts college with low tuition, we get far more of such students than comparable private colleges. (At Carleton, the farmer’s daughter that I met and married was one of only two such students in the entire college.) Often 20% of our student body will be made up of first-generation college students, something that would please New York Times columnist Ross Douhat, who complains that colleges are ignoring class diversity (see his Monday column).

Allow me to boast about St. Mary’s College of Maryland for a moment. When we underwent accreditation review a few years ago, the head of the review team (the president of Macalester College) was amazed that these students were graduating at an 80% rate, not far behind the 85% percentage rate of other students. Few other schools in the country come anywhere close, he said.

The secret of our success is that we track these students closely. We know that they face challenges that most students don’t encounter. Their family culture often has not prepared them for college, they are uncomfortable asking for help when they are in trouble, and many families expect them to run home every time there is an emergency (often they are the most responsible members of their families). I have seen one instance of a drug-addicted mother trying to get her hands on her son’s scholarship money (she couldn’t because it went straight to tuition).

In our special summer session, the students (like all this year’s in-coming students) were to read Huckleberry Finn and write a short, 250-word essay on a theme that appears in the book. Two of my students, a first-generation Guatemalan man and an African American woman, chose to write on Huck’s education. Both Juan and Tahisha (not their real names) defended Miss Watson.

It made sense as I thought about it. From their perspective, Huck was the undisciplined classmates that they saw all around them. Good for Miss Watson, then, for caring about Huck’s future and enforcing some rules. Tahisha was fascinated by how some students do well when they have terrible parents and others, from better backgrounds, turn to drugs and crime. While she acknowledged that Huck was an orphan and the child of a terrible father, she put him more into the second category and saw him wasting his opportunities. She didn’t like how he slid back into his old ways when Pap takes him off to the cabin in the woods.

She went even further. She actually felt that Huck should have informed Miss Watson about Jim once Jim is captured. By just doing what he “felt like doing,” Huck was, once again, being undisciplined. This startling conclusion makes sense if you consider that Tahisha was seeing Huck and Jim through the lens of gang membership. Huck had Jim’s back whereas he should have gone to the authorities.

At this point in our discussion, however, cognitive dissonance set in. After all, did she, an African American woman, really want to be defending slavery or complaining about an interracial friendship? At that moment I could see the light break in—as a teacher I live for these moments—and she said excitedly that she could write her essay as two sides of an argument. The track that she had been on—a perfectly understandable track given her own disciplined drive to attend college—had just been complicated by her sudden awareness that one can have two competing value systems, each with something to be said for it. She started rethinking the book.

All of this occurred from her having read a novel, written a 250 word essay, and engaged in a 25 minute conversation with a teacher. I told Tahisha that she was going to do just fine in college. In fact, she was going to step into her strengths and be magnificent.

Meanwhile, I too knew that I had been given a gift. An unexpected response to Huckleberry Finn had helped me understand better the world that some of my students come from. All in all, it was a remarkable day.

One Trackback

[…] been thinking about the impact of literature on our lives, and your post on Miss Watson sparked a recollection of one of my MBA students who illustrates this […]