Friday

Sometimes when I have a great conversation, I write it down to preserve it. I therefore report on yesterday’s discussion with John Stubbs, a literary historian with books on John Donne, Jonathan Swift, and the cavalier poets. John currently teaches at Ljubljana’s Bezigrad high school, where in 1995 I taught one of the classes he’s currently teaching (but only for six weeks).

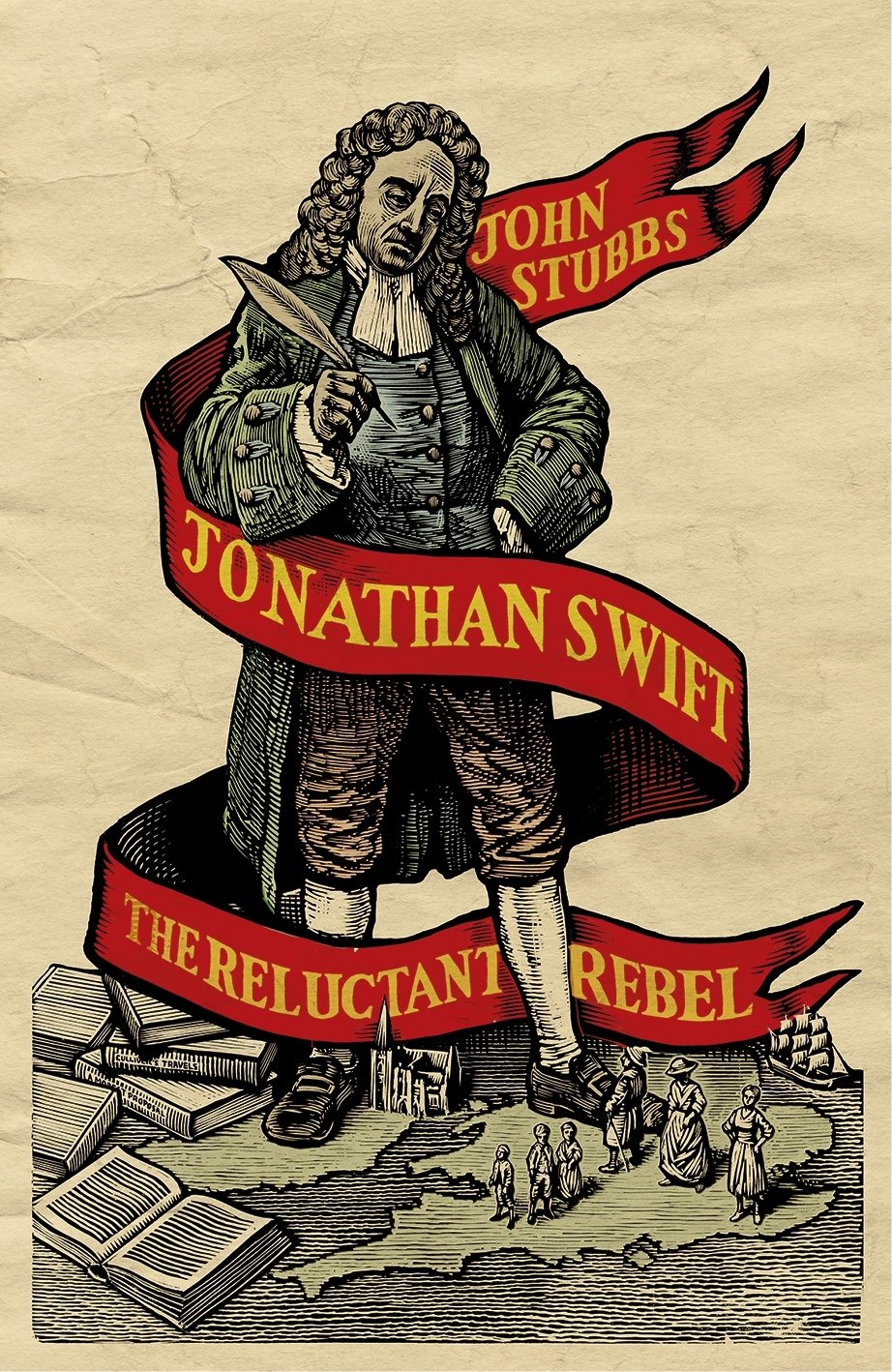

Jonathan is married to a Slovenian lawyer (as of this past Tuesday, a judge) and appears to speak excellent Slovene. I met him through my colleague Jason Blake, and I grilled him about his projects over coffee and delicious pastries in a Ljubljana cafe. His book Jonathan Swift, the Reluctant Rebel (Viking/Penguin, 2017) looks at how the satirist was drawn into defending the Irish almost against his will. Swift challenged English stereotypes of Irish Catholics as brutes and saw Ireland’s real problem as colonization. He exposed this most famously, of course, in “Modest Proposal,” but he fought for Ireland in other ways as well.

Meanwhile, in Reprobates: The Cavaliers (Norton, 2012), John upends many of the simple binaries about who sympathized with whom in the war between the royalists and the Puritans. He shows that some Puritans behaved as cavaliers and that some cavaliers shared radical ideas with Puritans. We learn that Milton, Marvell, and the cavalier poets don’t fit neatly into the boxes we assign them.

John’s books interest me because I write frequently about his subjects. But I was also interested in what draws someone to literary biography. For decades, biographies were, if not frowned upon in literary studies, at least not encouraged or celebrated. In the days of formalism, most scholars focused only on text and considered authors irrelevant, those who paid attention to them being guilty of “the intentional fallacy.” The structuralists and deconstructionists weren’t much better, with Roland Barthes proclaiming “the death of the author.” (In Barthes’s view it is “language that speaks,” not the writer.)

John’s books are delightfully written, which means he has departed from his dissertation concerns, where he tracked Shakespeare’s use of a particular rhetorical figure in a study that he says became increasingly murky. I sympathized as I too wrote a dissertation that I’m glad is behind me. (My subject was the cranky novelist Tobias Smollett, whom I didn’t particularly like.) We both agreed that, while dissertations are perhaps necessary, it’s much more fun to write about literature now that we’re not facing academic pressure.

John turned to biography because authors like Milton and Marvell, as he had been taught them, seemed to float in a void. He said that he loves stories, and his books are written with a novelist’s eye. I noted that such love sets him apart from the literary theorists I waded through in the 1980s. For instance, many deconstructionists regarded literature as second rate philosophy (even though they themselves were literary scholars) because literature traffics in deceptive narrative and simulacrums of reality. We should study fiction’s fictionality, they asserted, and not the insights it provides into human nature and other real life concerns.

I told John that, while I made a good faith effort to understand the deconstructionists, I found myself craving, in a visceral way, the concreteness of character, setting, plot, and image. I ultimately found abstract theory too bloodless.

I noted that Robert Scholes’s The Crafty Reader believes literature teachers miss out on a valuable asset when they ignore biography. If you want to become an accomplished reader, Scholes says, begin “by devoting a lot of time to a single poet whose poems clearly emerge from and connect to the ordinary events of human life.” The poetry becomes far more accessible once one does so.

As we talked on, I thought of Anne Elliot’s observation (in Jane Austen’s Persuasion) that good company is “the company of clever, well-informed people, who have a great deal of conversation.” (Mr. Elliot replies that “that is not good company; that is the best.”) I was rejuvenated by this new acquaintance and reflected that, were I not now retired, I would be up to my eyeballs in student essays. Life felt good.