Thursday

It’s seldom good when your college ends up on the front page of The Washington Post. A series of arson incidents (admittedly fairly small—a bulletin board here, a basket of laundry there); some racist, sexist, anti-Semitic, and homophobic messages painted on beer cans; and a student wearing a Confederate shirt to a basketball game have come together in a perfect storm that caught the eye of a reporter.

Yesterday morning’s classes were canceled for an all-campus meeting in the gym, where people talked about the concerns and discussed steps we could take. The place was packed, and many students voiced their anger and disappointment at how we have strayed from “the St. Mary’s Way,” a code of conduct designed to promote mutual respect amongst all members of the community.

There were also positive moments as people made concrete suggestions for steps forward. Many expressed their love for St. Mary’s and expressed their appreciation for the forum.

Today’s post describes how I have folded the incidents into my teaching. Applying literature to urgent issues is one way of affirming its value.

The forum ended right before my Early British Literature survey and I knew, as I listened to the speakers, that George Herbert would not resonate with my students that day. I therefore scrambled the syllabus, pulling up Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko and pushing everything else back. Oroonoko examines how an attempted friendship between a colonialist white woman and a male slave is undermined by what today we would call systemic racism.

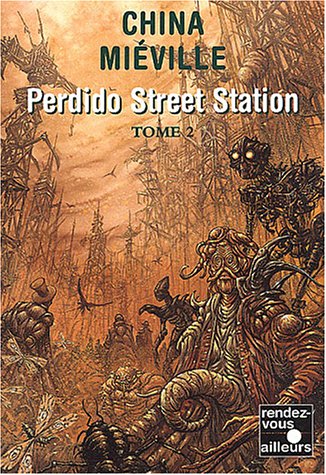

I didn’t have to shift anything around in my British Fantasy class, where on Tuesday we discussed China Miéville’s Victorian steampunk novel Perdido Street Station. The novel features a multicultural city in which various subgroups interact and sometimes clash. The subgroups include regular humans, beetle-headed half-humans, walking cactus plants, giant slake moths, angels, and the city’s mob boss, named Mr. Motley, who is a “remade” combination of pretty much everything.

Easiest to apply to our situation was the poetry of Lucille Clifton, whose poetry we were reading last week when the offensive beer cans were found. Clifton taught for 18 years at St. Mary’s and wrote several poems specifically about race tensions here. How often does a major writer speak that directly to you?

Here’s a small sampling of what we talked about.

I’ve described in past posts (here and here) how Oroonoko can seem to confirm Aristotle’s assertion that friendship is impossible between people when the power differential is substantial. Time and again in the novella, a character will betray a friend when the inducements are there to do so. Narrator Behn and African prince Oroonoko are friends but she then takes advantage of their intimacy to spy on him at the behest of the plantation owners. Plantation overseer Trefry and Oroonoko are friends but Trefry manages to be absent when the plantation owners break their word and torture Oroonoko following a failed slave revolt. Oroonoko and the lower class African slaves are friends but he then promises Trefry to obtain more slaves for him in exchange for his own freedom.

What threatens friendships across race lines at St. Mary’s, I asked. While some of the students, all white, argued that there weren’t obstacles, the students of color weren’t so sure. The differences lay in life experiences, which led to different students looking at a Confederate flag and seeing two entirely different things. And where students from black inner city neighborhoods saw threats all around them, students from white suburbia saw only a benign campus. Those different perspectives sabotage potential friendships.

Fortunately, slavery is not dividing us. These differences can be surmounted, we agreed, if people make a sustained effort to talk to each other and listen to each other. Since a major aspect of privilege is not having to think about certain things, those who are privileged have a special obligation to listen closely.

In Monday’s Introduction to Literature class, we had the opportunity to approach privilege from an angle that half the class understood immediately. In “Wishes for Sons” (which I’ve written about here), my women students noted that the men in the class had the privilege of not having to think about menstruation. They told stories of insensitive fathers, brothers, and boyfriends.

Clifton, I pointed out, is always sensitive to those whose voices are not being heard. It could be African Americans in one poem, women in another, children with disabilities in another (as in “grandma, we are poets,” about Lucille’s autistic grandson).

In British Fantasy we talked about how, in a post-modern society, the old established norms are no longer operative. Miéville offers a nice example of this early in Perdido Street Station where Isaac, a human, is dating Lin, who is a khepri—someone with a human body but a beetle’s head. Or at least, that is how he describes her. But she points out that his articulation reveals his anthrocentrism and that it is equally valid to describe him as having a khepri body with a head that looks somewhat like a gibbon.

Donald Trump’s rhetoric, which I think has raised race tensions on our campus and around the country, appeals to white voters who are panicking over losing their accustomed dominance and becoming just another of America’s minorities, albeit the major minority. In other words, with the browning of America, they can no longer confidently posit themselves as the norm and everyone else as the deviation. Such identity anxiety goes a long way towards explaining the political temper tantrum we are witnessing.

Literature can’t end racial tension, but it can gives us a framework for understanding and talking about it.