Wednesday

A smart Gene Robinson column in The Washington Post has sent me to August Wilson’s plays, starting with Fences. This in order to understand “the Joe Biden voter.”

Robinson is teasing the media here over its obsession with “the Trump voter”:

After Donald Trump won in 2016, the media and academia embarked on a numbingly comprehensive sociological and anthropological examination of “the Trump voter.” Reporters and researchers swarmed what seemed like every bereft factory town in the industrial Midwest, every hill and hollow of Appalachia, every windswept farming community throughout the Great Plains. I’m pretty sure television crews did, in fact, bring us reports from every single diner in the contiguous United States — at least, those where at least one regular patron wears overalls.

For a while, the “economic anxiety” explanation prevailed until it was learned that many Trump voters had incomes of over $100,000 a year. We’ve since learned that Trump’s racism probably was more of a factor—which is to say, status and culture anxiety trumped economic anxiety. In any event, if Trump voters have gotten most of the attention over the past four years, then maybe Biden voters should now.

Robinson begins his column with a series of question:

Who are they and what drove them to vote in such huge numbers, even during a pandemic? What makes them tick? Is it culture? Tribalism? Race? How did they come to their worldview, and why do they cling to it so passionately? What do they mean for the future of American democracy?

I’m talking about the opaque and inscrutable Joe Biden voter, of course.

To answer these questions, Robinson suggests that we set aside “those dog-eared copies of J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy” and turn to a different set of readings. Given that Biden captured 87% of the black vote and that black voters reversed his fortunes in the South Carolina primary, Robinson starts there.

He recommends books on “the great migration,” one of the largest population movements in the history of the world, where former slaves and their descendants flooded into northern cities looking for new opportunities. Robinson also recommends reading or streaming Wilson’s plays:

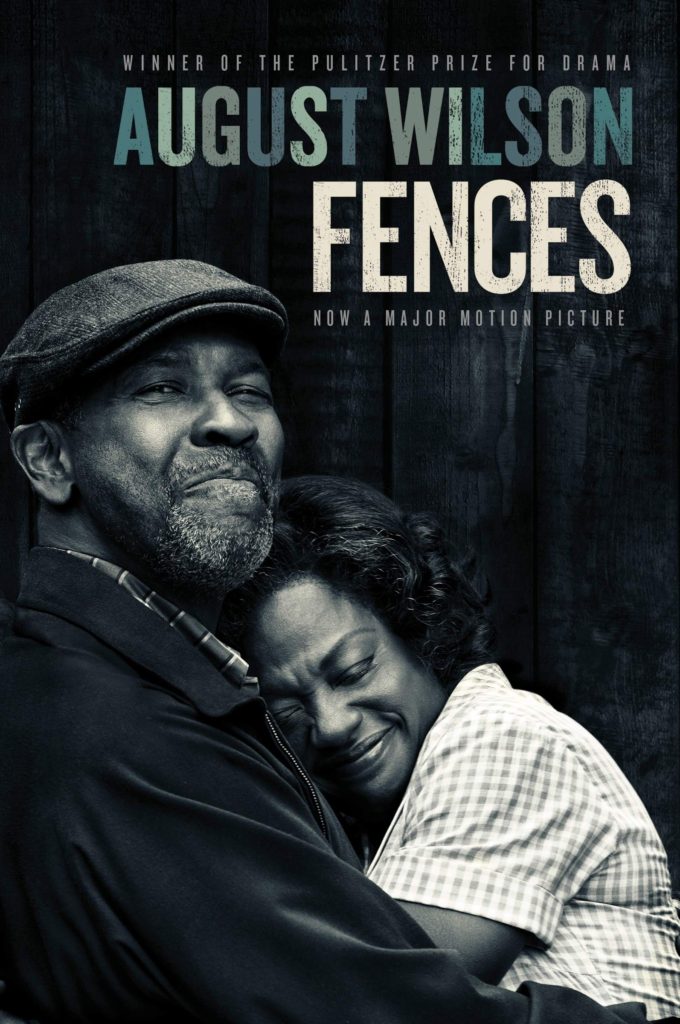

If you’re more of an audiovisual learner, scroll through your streaming service until you find one of the film adaptations of the seminal plays by August Wilson, who lived and wrote in Pittsburgh — The Piano Lesson, say, or Fences. (The most recent Wilson production, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” starring Viola Davis and the late Chadwick Boseman, won’t be available for streaming for another few weeks.

Fences is about Troy Maxson, a garbage collector in a Pittsburgh-like city, and his interactions with his wife, his two sons, a former cellmate, and a brother who has been brain damaged in World War II. We learn about Maxson’s clashes with an abusive sharecropper father, his stint in prison for robbery and manslaughter, and his current union job where he aspires to be a driver rather than one of the men handling the cans. One son sponges money off of him, the other is an aspiring college athlete who needs his signature for a university scholarship.

Maxson is alternatively sympathetic and infuriating. Although we don’t approve, we can understand why he sabotages his son’s sports career and why he commits adultery despite having an admirable wife. We also applaud how he passes along good values to his sons, faithfully turns over his paycheck to his wife every month, and stands up to his employers for his rights. In short, we don’t see him as a stereotype but as a complex human being, which is why Robinson recommends the play.

Robinson doesn’t go into why there’s a four in five chance that such a Wilson character would be a Joe Biden voter (Biden captured 82% of the black male vote), but we can see many reasons: Biden’s support for labor unions, for hard working Americans, for equal rights and equal opportunity, for racial justice, for second-chance opportunities for convicted felons, and for protection against loan sharks. (The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, once it’s allowed to operate again, could help Maxson out of an onerous furniture debt he’s been paying for years.)

One can see why someone with this perspective might not take a chance on a Bernie Sanders or an Elizabeth Warren. To dream big–to swing for the fences–is to set yourself up to be crushed. Maxson’s son Cory should set his sights on a job at the A&P, Maxson feels, not on college. (On the other hand, I could see Cory, who eventually joins the Marines, becoming a Bernie Bro in a later age.)

Although he has a criminal record and out-of-wedlock children, Maxson doesn’t fit racist stereotypes. He doesn’t ask for handouts, he takes responsibility for his actions, he works hard to maintain his household, he looks after his injured brother, and he cares about his wife and sons (even though it doesn’t look like it at times). Here he is trying to explain to his wife of 18 years why he has a brief fling. The ellipses are his pauses:

Troy: Rose, I done tried all my life to live decent…to live a clean…hard…useful life. I tried to be a good husband to you. In every way I knew how. Maybe I come into the world backwards, I don’t know. But…you born with two strikes on you before you come to the plate. You got to guard it closely…always looking for the curve-ball on the inside corner. You can’t afford to let none get past you. You can’t afford a call strike. If you going down…you going down swinging. Everything lined up against you. What you gonna do. I fooled them, Rose. I bunted. When I found you and Cory and a halfway decent job…I was safe. Could nothing touch me. I wasn’t gonna strike out no more. I wasn’t going back to the penitentiary. I wasn’t gonna lay in the streets with a bottle of wine. I was safe. I had me a family. A job. I wasn’t gonna get that last strike. I was on first looking for one of them boys to knock me in. To get me home.

Rose: You should have stayed in my bed, Troy.

Troy: Then when I saw that gal…she firmed up my backbone. And I got to thinking that if I tried…I just might be able to steal second. Do you understand after eighteen years I wanted to steal second.

Rose: You should have held me tight. You should have grabbed me and held on.

Troy: I stood on first base for eighteen years and I thought…well, goddamn it…go on for it!

Rose today would definitely be for Biden, who won black women 92-8. Rose can afford to dream even less than Troy and would thus be leery of taking chances on a dream candidate. After all, she’s raising his kids, including (by the end of the play) the daughter of his mistress. She would be attuned to Obamacare (although Troy might get health insurance through his job), Aid to Families with Dependent Children, and food stamps. Look at the hard pragmatism that marks her response to Troy:

I been standing with you! I been right here with you, Troy. I got a life too. I gave eighteen years of my life to stand in the same spot with you. Don’t you think I ever wanted other things? Don’t you think I had dreams and hopes? What about my life? What about me? Don’t you think it ever crossed my mind to want to know other men? That I wanted to lay up somewhere and forget about my responsibilities?That I wanted someone to make me laugh so I could feel good? You not the only one who’s got wants and needs. But I held on to you, Trooy. I took all my feelings, my wants and needs, myd reams…and I buried them inside you. I planted a seed and watched and prayed over it. I planted myself inside you and waited to bloom. And it didn’t take me no eighteen years to find out the soil was hard and rocky and it wasn’t never gonna bloom.

Later on, after Troy has died, she explains her choice to Cory, who initially doesn’t want to attend the funeral:

I took on his life as mine and mixed up the pieces so that you couldn’t hardly tell which was which anymore. It was my choice. It was my life and I didn’t have to live it like that. But that’s what life offered me in the way of being a woman and I took it. I grabbed hold of it with both hands.

After recommending Wilson’s play, Robinson goes on to suggest other books that help explain why various constituencies voted for Biden. To understand white suburbia’s horror for Trump, for instance, he points to Bob Woodward’s Rage and Fear, Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist (“a must-read in many of those circles”), and Jacob Soboroff’s Separated: Inside an American Tragedy, about children torn from their asylum-seeking parents.

Robinson then concludes his piece with a shoutout to Langston Hughes:

It turns out “the Biden voter” isn’t so mysterious and unknowable after all. “I, too, am America,” wrote the poet Langston Hughes. And if you haven’t read him yet, add him to the pile, too.

Yes, Hughes articulates a multicultural vision of America that drove many of us Biden voters to the polls. We didn’t just vote against Trump but for something noble and generous.

I, too, sing America. I am the darker brother. They send me to eat in the kitchen When company comes, But I laugh, And eat well, And grow strong. Tomorrow, I’ll be at the table When company comes. Nobody’ll dare Say to me, “Eat in the kitchen,” Then. Besides, They’ll see how beautiful I am And be ashamed— I, too, am America.