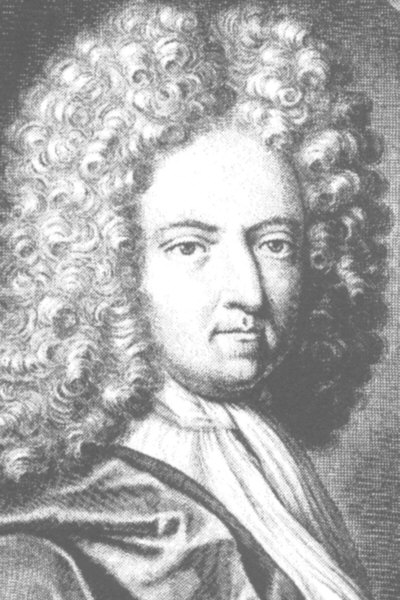

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

My daughter-in-law sent me a wonderful poem by Daniel Defoe, “A True Born Englishman,” posted by Andrew Sullivan in response to a Patrick Buchanan editorial. Buchanan’s column was one of those hateful “they’re taking our country away from us” pieces, and Sullivan rightly asks who this “us” is.

As Sullivan’s translates it, Buchanan is panicked now that whites are not the only ones having a say in the running of the country. But of course, the “us” includes people of color as well as whites, even though they have long been unrepresented in the halls of power.

Buchanan must know that the “us” once excluded the Irish. Then again, maybe that’s the source of some of his fear.

Defoe’s poem is going after those English who were upset at having William of Orange as their king (William married Mary and they ruled jointly). The poem makes clear that people have been illogically arguing that they were “first” for a long time and in other countries than this one. There’s no such thing as a pure Englishman any more than a pure American. Defoe writes,

The western Angles all the rest subdu’d;

A bloody nation, barbarous and rude:

Who by the tenure of the sword possest

One part of Britain, and subdu’d the rest

And as great things denominate the small,

The conqu’ring part gave title to the whole.

The Scot, Pict, Britain, Roman, Dane, submit,

And with the English-Saxon all unite:

And these the mixture have so close pursu’d,

The very name and memory’s subdu’d:

No Roman now, no Britain does remain;

Wales strove to separate, but strove in vain:

The silent nations undistinguish’d fall,

And Englishman’s the common name for all.

Fate jumbled them together, God knows how;

What e’er they were they’re true-born English now.

While I don’t think that poetry has the power to change the mind of a bigot, there is something about well crafted poetic wit that can bolster the spirits of those who are struggling against racism and intolerance. It is as though a voice reaches through time and from a higher plane to provide moral assistance.

There is a comic version of the kind of people that Defoe was challenging in Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones,written about 40 years later. Squire Western, the buffoonish father of the heroine, is always railing against the central government and those people who supported the Hanoverian Georges, kings brought over to rule England in lieu of the Catholic Stewarts. He gets in a violent argument with his sister about the raising of his daughter and suddenly politics enters in.

As you read the passage, think of Western as one of our own “firsters” and his equally prejudiced sister as someone who believes in a strong centralized authority. Both are equally selfish and equally insensitive towards the well-being of Sophia:

“O! more than Gothic ignorance,” answered the lady. “And as for your manners, brother, I must tell you, they deserve a cane.”—“Why then you may gi’ it me, if you think you are able,” cries the squire; “nay, I suppose your niece there will be ready enough to help you.”—“Brother,” said Mrs. Western, “though I despise you beyond expression, yet I shall endure your insolence no longer; so I desire my coach may be got ready immediately, for I am resolved to leave your house this very morning.”—“And a good riddance too,” answered he; “I can bear your insolence no longer, an you come to that. Blood! it is almost enough of itself to make my daughter undervalue my sense, when she hears you telling me every minute you despise me.”—“It is impossible, it is impossible,” cries the aunt; “no one can undervalue such a boor. boor.”—“Boar,” answered the squire, “I am no boar; no, nor ass; no, nor rat neither, madam. Remember that—I am no rat. I am a true Englishman, and not of your Hanover breed, that have eat up the nation.”—“Thou art one of those wise men,” cries she, “whose nonsensical principles have undone the nation; by weakening the hands of our government at home, and by discouraging our friends and encouraging our enemies abroad.”—“Ho! are you come back to your politics?” cries the squire: “as for those I despise them as much as I do a f—t.” Which last words he accompanied and graced with the very action, which, of all others, was the most proper to it. And whether it was this word or the contempt exprest for her politics, which most affected Mrs. Western, I will not determine; but she flew into the most violent rage, uttered phrases improper to be here related, and instantly burst out of the house. Nor did her brother or her niece think proper either to stop or to follow her; for the one was so much possessed by concern, and the other by anger, that they were rendered almost motionless.

The squire, however, sent after his sister the same holloa which attends the departure of a hare, when she is first started before the hounds. He was indeed a great master of this kind of vociferation, and had a holla proper for most occasions in life.

Defoe’s comic satire and Fielding’s comic depictions can perhaps help us get some emotional distance from the passions that are whipping up people these days, in tea bag gatherings and hate-filled websites. Better, as Lincoln would have said, to laugh than to cry.