Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Wednesday

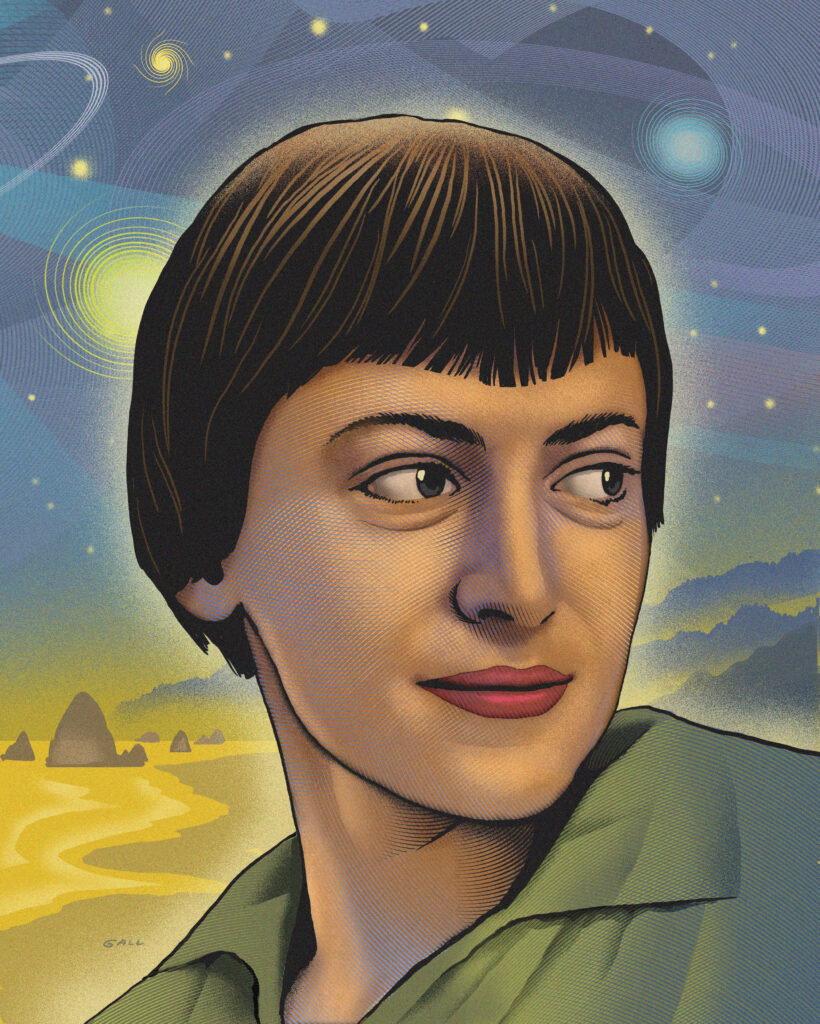

An Ursula K. Le Guin short story is helping me understand some of the batshit craziness (to use the technical term) that we have been witnessing in some of Trump followers. I’m thinking of how MAGA thugs have been threatening workers from FEMA (the Federal Emergency Management Agency) in their rescue and clean-up efforts after the two hurricanes. Meanwhile Marjorie Taylor Green—she of “Jewish space lasers” fame—has informed us that Democrats are sending the hurricanes to devastate Trump areas.

And then, as I mentioned Monday, there are portions of MAGA have all but become a death cult, sometimes deliberately exposing themselves to Covid. And I suppose I should mention those Christian fundamentalists who believe that the end times have arrived.

We’re not only hearing apocalyptic talk from the right, however. There are well-founded warnings (in my opinion) about cataclysmic climate change and, if Trump triumphs in the election, about a fascist takeover that would end America’s democratic experiment. The world, especially with the internet, has shrunk considerably while the things we do—from hydrocarbons to plastic production—are having outsized effects. No wonder we seem simultaneously to have more and less control than we have ever had. For the Marjorie Taylor Greens, maybe targeted hurricanes is the logical next step in this evolution.

“Things” is a short story about an island population that is facing extinction, although we never know from what. The islanders have two responses: there are those who weep and those who rage. The Ragers, who resemble some of our MAGA nihilists, destroy everything upon which people depend. They also target anyone who doesn’t think like them. As one of them tells the brickmaker protagonist,

Things, things! Free yourself of things, Lif, from the weight that drags you down! Come with us, above the ending of the world!

This freedom sometimes takes the form of active destruction, with the Ragers burning crops, killing livestock, and tearing down local businesses.

Neither a Rager nor a Weeper, Lif takes a third path. Although he knows the task is impossible, he begins using his bricks to build an underwater road to the other islands. In this he has the help of a widow and her child. The Ragers would attack him if they realized he was doing something constructive, but thinking that he is merely drowning his bricks, they applaud him.

After he has used up all his bricks, Lif assures the widow that they will trod this road together:

By God! said Lif, thinking of his underwater road across the sea that went for a hundred and twenty feet, and the sea that went on ten thousand miles from the end of it–I’ll swim there! Now then, don’t cry, dear heart. Would I leave you and the little rat here by yourselves?

“Things” ends ambiguously in a way that is characteristic of Le Guin’s short stories. Lif and the widow wade to the end of the road and then, up to their chests in water, prepare to take the last step. At that moment Lif thinks that he sees the whiteness of a sail, a “dancing light above the waves, dancing on towards them and towards the greater light that grew behind them”:

Wait, the call came from the form that rode the grey waves and danced on the foam, Wait! The voices rang very sweet, and as the sail leaned white above him he saw the faces and the reaching arms, and heard them say to him, Come, come on the ship, come with us to the Islands.

Hold on, he said softly to the woman, and they took the last step.

One could read this ending as death—who knows what really lies beyond that great divide?– or one could read it as an assertion of radical hope. In certain ways, it resembles the existentialists’ Sisyphus, about whom Albert Camus writes,

Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

For Le Guin, however, I think it means more than this. After all, Lif’s road goes forward rather than in a circle. I think the author is saying that if we refuse to surrender to either raging or weeping, using instead our tools and our talents in the world that we have been given, unforeseen possibilities may open up. True, it may be, as Ulysses puts it in Tennyson’s poem, “that the gulfs will wash us down.” But it also may be the case that “we shall touch the Happy Isles,/ And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.”

In any event, we will dwell in possibility rather than in despair, in hope rather than in hatred. That’s not a bad way to spend the remaining time we have on earth.