Spiritual Sunday

Last Sunday I reported on a Lenten series featuring Flannery O’Connor that my colleague Ben Click is teaching. I attended the second class, on “The Artificial Nigger,” and, as with Ben’s ideas on “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” came away impressed with O’Connor’s religious exploring. Ben sees “Artificial Nigger” as a Lenten tale of pride humbled and grace received.

The story is about a grandfather from rural Georgia who takes his grandson Nelson to Atlanta to make him realize how dependent he is on the grandfather:

“The day is going to come,” Mr. Head prophesied, “when you’ll find you ain’t as smart as you think you are.” He had been thinking about this trip for several months but it was for the most part in moral terms that he conceived it. It was to be a lesson that the boy would never forget. He was to find out from it that he had no cause for pride merely because he had been born in a city. He was to find out that the city is not a great place. Mr. Head meant him to see everything there is to see in a city so that he would be content to stay at home for the rest of his life. He fell asleep thinking how the boy would at last find out that he was not as smart as he thought he was.

Of course, the trip doesn’t go as planned. Guilty of an overweening pride, Mr. Head (not Mr. Heart, Ben noted) commits a Peter-like betrayal in a moment of panic. He has played a trick on Nelson, only to see the boy, in his own panic, collide with a woman and knock her over:

Mr. Head was trying to detach Nelson’s fingers from the flesh in the back of his legs. The old man’s head had lowered itself into his collar like a turtle’s; his eyes were glazed with fear and caution.

“Your boy has broken my ankle!” the old woman shouted. “Police!”

Mr. Head sensed the approach of the policeman from behind. He stared straight ahead at the women who were massed in their fury like a solid wall to block his escape, “This is not my boy,” he said. “l never seen him before.”

He felt Nelson’s fingers fall out of his flesh.

After such a betrayal, what forgiveness?

Mr. Head began to feel the depth of his denial. His face as they walked on became all hollows and bare ridges. He saw nothing they were passing but he perceived that they had lost the car tracks. There was no dome to be seen anywhere and the afternoon was advancing. He knew that if dark overtook them in the city, they would be beaten and robbed. The speed of God’s justice was only what he expected for himself, but he could not stand to think that his sins would be visited upon Nelson and that even now, he was leading the boy to his doom.

Ben made the point that, for the first time in the story, Mr. Head has begun to think not of himself but of Nelson, which is a step in the right direction. What ultimately brings them back together is their encounter with an African American statue in someone’s lawn:

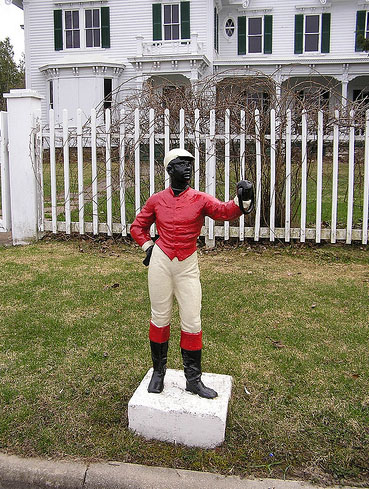

He had not walked five hundred yards down the road when he saw, within reach of him, the plaster figure of a Negro sitting bent over on a low yellow brick fence that curved around a wide lawn. The Negro was about Nelson’s size and he was pitched forward at an unsteady angle because the putty that held him to the wall had cracked. One of his eyes was entirely white and he held a piece of brown watermelon.

Mr. Head stood looking at him silently until Nelson stopped at a little distance. Then as the two of them stood there, Mr. Head breathed, “An artificial nigger!”

It was not possible to tell if the artificial Negro were meant to be young or old; he looked too miserable to be either. He was meant to look happy because his mouth was stretched up at the corners but the chipped eye and the angle he was cocked at gave him a wild look of misery instead.

“An artificial nigger!” Nelson repeated in Mr. Head’s exact tone.

The two of them stood there with their necks forward at almost the same angle and their shoulders curved in almost exactly the same way and their hands trembling identically in their pockets.

Mr. Head looked like an ancient child and Nelson like a miniature old man. They stood gazing at the artificial Negro as if they were faced with some great mystery, some monument to another’s victory that brought them together in their common defeat. They could both feel it dissolving their differences like an action of mercy. Mr. Head had never known before what mercy felt like because he had been too good to deserve any, but he felt he knew now.

The symbol is ambiguous. On the one hand (this was Ben’s argument), the two see their own suffering in this African American figure, and it is through their recognition of the humanity of the Other that they are able to forgive and be forgiven. Ben linked this to the moment in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” when the smug grandmother sees the humanity of the mass murderer and reaches out to touch him.

Making such a connection is particularly significant in this story as Mr. Head has been teaching Nelson how to be a racist all throughout the trip. Nelson ends up with prejudices that he didn’t have at the beginning of the day. Perhaps they are saved because they rise above their racial fears and embrace a common humanity.

The element of race in the story suggests an alternative explanation, however–that the African American figure works as a cleansing scapegoat here. Perhaps Mr. Head and Nelson come together because, like the self-satisfied Pharisee, they thank God they are not like other people. Christianity can become tribalistic, with group members bonding out of fear of the unknowable world. I’ve explored the scapegoating interpretation of the story here.

I had to acknowledge, however, that Ben’s more generous reading seems borne out by the story’s penultimate paragraph, which shows a human being fully admitting his sins and gazing in awe at God’s infinite power to forgive:

Mr. Head stood very still and felt the action of mercy touch him again but this time he knew that there were no words in the world that could name it. He understood that it grew out of agony, which is not denied to any man and which is given in strange ways to children. He understood it was all a man could carry into death to give his Maker and he suddenly burned with shame chat he had so little of it to take with him. He stood appalled, judging himself with the thoroughness of God, while the action of mercy covered his pride like a flame and consumed it. He had never thought himself a great sinner before but he saw now that his true depravity had been hidden from him lest it cause him despair. He realized that he was forgiven for sins from the beginning of time, when he had conceived in his own heart the sin of Adam, until the present, when he had denied poor Nelson. He saw that no Sin was too monstrous for him to claim as his own, and since God loved in proportion as He forgave, he felt ready at that instant to enter Paradise.

Then again, the very last paragraph shows us a Nelson with his new prejudices seemingly fixed:

Nelson, composing his expression under the shadow of his hat brim, watched him with a mixture of fatigue and suspicion, but as the train glided past them and disappeared like a frightened serpent into the woods, even his face lightened and he muttered, “I’m glad I’ve went once, but I’ll never go back again!”

Mr. Head and Nelson may think that they have returned to the Garden of Eden and regained their innocence and that the tempting serpent has fled, but this sounds like a case of arrested development. Our discussion ended with us debating this point.

Ben argued that, if Mr. Head has had a genuine revelation, then maybe he will go on to teach Nelson love rather than fear, which is a powerful way to combat racism. Nelson may be drawing the wrong lessons now—that urban settings filled with Blacks should be avoided at all costs—but he’s only a child and maybe he’ll grow up to be someone different. All is possible with God.

How about this for an approach: we should let our actions in response to the story determine its meaning. We can settle for a false grace, one rooted in our smug superiority over others who don’t look like us or believe like us. Or we can draw on the humility of Christ and step past our pride, loving all our neighbors–all of them–as we love ourselves.

There are both kinds of Christians in America today. Tribal Christians, like tribal Muslims and tribal Jews, generally make the most noise. Maybe, through her ambiguous ending, O’Connor is challenging us to make a choice.

One Trackback

[…] O’Connor, a southern author who handles race and class issues in a far more sophisticated way, once remarked about Mockingbird fans, “It’s interesting that all the folks that are […]