Thursday

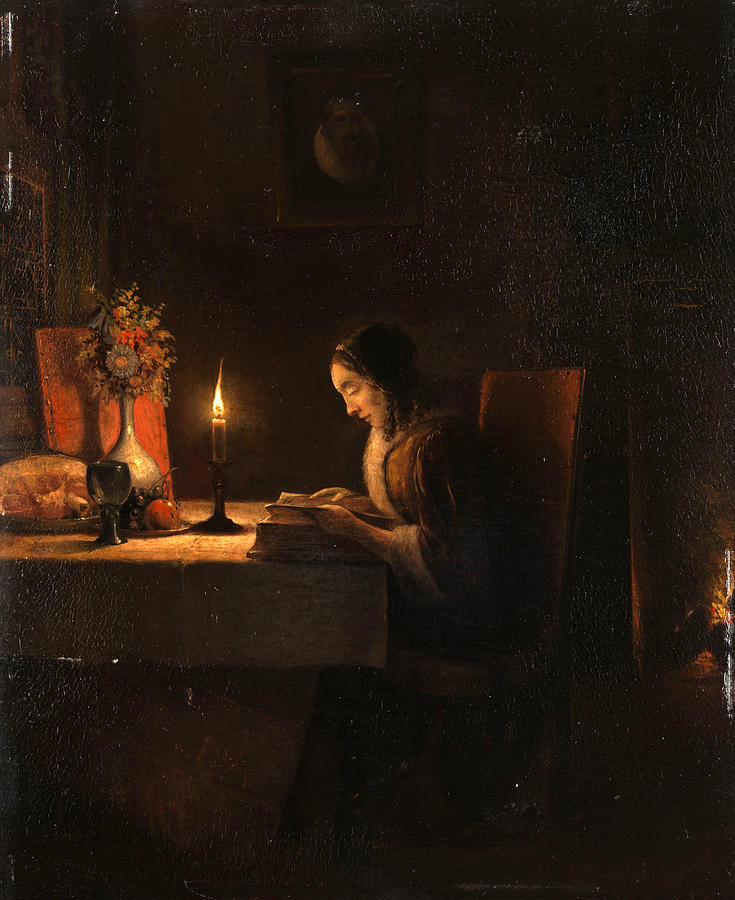

I’ve been rereading Daniel Defoe’s extraordinary historical novel Journal of the Plague Year (1722), about the great London plague of 1665 and have found many disconcerting parallels with our own situation. As always with these posts, I must acknowledge that COVID-19 is nowhere near as lethal as the illnesses that show up in novels, but in some ways that makes the parallels more unsettling.

Defoe has been described as the father of both the novel and modern journalism, and sometimes it’s not clear when he’s writing which. Robinson Crusoe, for instance, was originally regarded as an actual first-hand account, and the same is true of Plague Year. To be sure, narrator H.F. may be based on Defoe’s uncle Henry Foe, who kept actual journals of the plague, and Defoe appears to have done a fair amount of research to get details right. But he also uses character narratives, some undoubtedly invented, to capture the drama and the intensity of the plague.

Here are a few of the parallels. For instance, early during the outbreak, people play games with the numbers, trying to persuade themselves that the sickness will just go away:

The people showed a great concern [at the first two case of the plague], and began to be alarmed all over the town, and the more, because in the last week in December 1664 another man died in the same house, and of the same distemper. And then we were easy again for about six weeks, when none having died with any marks of infection, it was said the distemper was gone; but after that, I think it was about the 12th of February, another died in another house, but in the same parish and in the same manner.

This turned the people’s eyes pretty much towards that end of the town, and the weekly bills showing an increase of burials in St Giles’s parish more than usual, it began to be suspected that the plague was among the people at that end of the town, and that many had died of it, though they had taken care to keep it as much from the knowledge of the public as possible.

One reason that people conceal the plague is because they are afraid of being locked in their homes. It’s an extreme version of sheltering in place:

It is true that the locking up the doors of people’s houses, and setting a watchman there night and day to prevent their stirring out or any coming to them, when perhaps the sound people in the family might have escaped if they had been removed from the sick, looked very hard and cruel; and many people perished in these miserable confinements which, ’tis reasonable to believe, would not have been distempered if they had had liberty, though the plague was in the house; at which the people were very clamorous and uneasy at first, and several violences were committed and injuries offered to the men who were set to watch the houses so shut up; also several people broke out by force in many places, as I shall observe by-and-by. But it was a public good that justified the private mischief, and there was no obtaining the least mitigation by any application to magistrates or government at that time, at least not that I heard of.

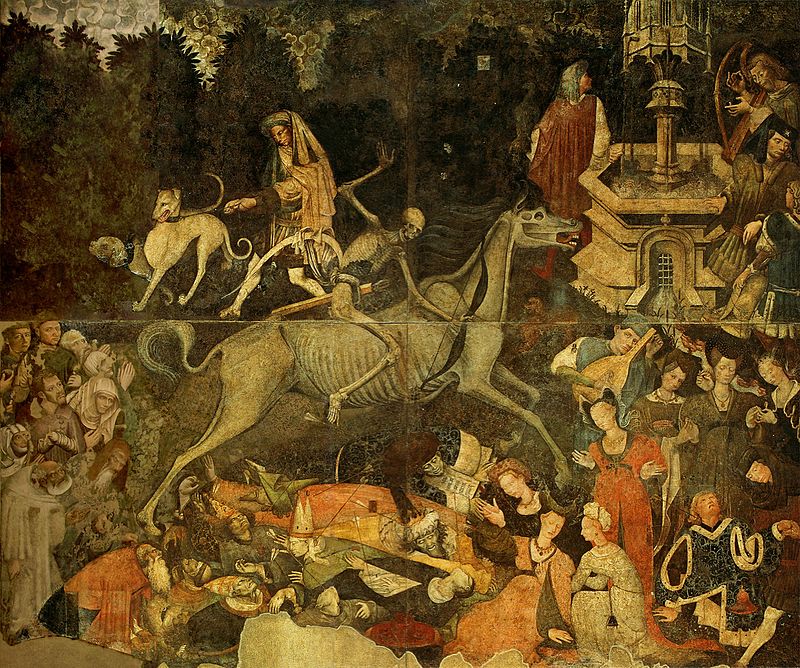

At the height of the plague, as currently is the case in Italy, the streets are deserted:

Business led me out sometimes to the other end of the town, even when the sickness was chiefly there; and as the thing was new to me, as well as to everybody else, it was a most surprising thing to see those streets which were usually so thronged now grown desolate, and so few people to be seen in them, that if I had been a stranger and at a loss for my way, I might sometimes have gone the length of a whole street (I mean of the by-streets), and seen nobody to direct me…

Because of their “terrors and apprehensions,” people are willing to swallow all kinds of fraudulent pronouncements, just as many have swallowed the shallow reassurances of the president and various Republican politicians:

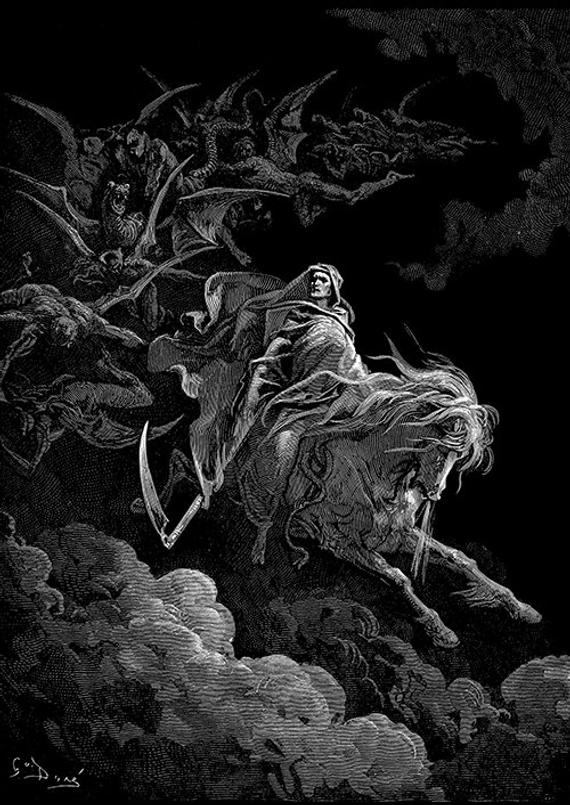

One mischief always introduces another. These terrors and apprehensions of the people led them into a thousand weak, foolish, and wicked things, which they wanted not a sort of people really wicked to encourage them to: and this was running about to fortune-tellers, cunning-men, and astrologers to know their fortune, or, as it is vulgarly expressed, to have their fortunes told them, their nativities calculated, and the like; and this folly presently made the town swarm with a wicked generation of pretenders to magic, to the black art, as they called it, and I know not what; nay, to a thousand worse dealings with the devil than they were really guilty of…

As always, the economically vulnerable suffer the worst:

[A]ll trades being stopped, employment ceased: the labor, and by that the bread, of the poor were cut off; and at first indeed the cries of the poor were most lamentable to hear…

Many of these were the miserable objects of despair which I have mentioned before, and were removed by the destruction which followed. These might be said to perish not by the infection itself but by the consequence of it; indeed, namely, by hunger and distress and the want of all things: being without lodging, without money, without friends, without means to get their bread, or without anyone to give it them…

Let anyone who is acquainted with what multitudes of people get their daily bread in this city by their labor, whether artificers or mere workmen—I say, let any man consider what must be the miserable condition of this town if, on a sudden, they should be all turned out of employment, that labor should cease, and wages for work be no more.

These people become so desperate for income that they are prepared to do anything—just like those service providers in our own society that we cannot do without:

It must be confessed that though the plague was chiefly among the poor, yet were the poor the most venturous and fearless of it, and went about their employment with a sort of brutal courage; I must call it so, for it was founded neither on religion nor prudence; scarce did they use any caution, but ran into any business which they could get employment in, though it was the most hazardous. Such was that of tending the sick, watching houses shut up, carrying infected persons to the pest-house, and, which was still worse, carrying the dead away to their graves.

As with us, many games and entertainments (“idle assemblies”) are closed down, including the following. Defoe here quotes from official documents:

Plays.

‘That all plays, bear-baitings, games, singing of ballads, buckler-play, or such-like causes of assemblies of people be utterly prohibited, and the parties offending severely punished by every alderman in his ward.Feasting prohibited.

‘That all public feasting, and particularly by the companies of this city, and dinners at taverns, ale-houses, and other places of common entertainment, be forborne till further order and allowance; and that the money thereby spared be preserved and employed for the benefit and relief of the poor visited with the infection.Tippling-houses.

‘That disorderly tippling in taverns, ale-houses, coffee-houses, and cellars be severely looked unto, as the common sin of this time and greatest occasion of dispersing the plague. And that no company or person be suffered to remain or come into any tavern, ale-house, or coffee-house to drink after nine of the clock in the evening, according to the ancient law and custom of this city, upon the penalties ordained in that behalf.

We also see social distancing measures, along with a 17th version of hand sanitizers:

It is true people used all possible precaution. When any one bought a joint of meat in the market they would not take it off the butcher’s hand, but took it off the hooks themselves. On the other hand, the butcher would not touch the money, but have it put into a pot full of vinegar, which he kept for that purpose. The buyer carried always small money to make up any odd sum, that they might take no change. They carried bottles of scents and perfumes in their hands, and all the means that could be used were used, but then the poor could not do even these things, and they went at all hazards.

As with us, commerce takes a beating:

It must not be forgot here to take some notice of the state of trade during the time of this common calamity, and this with respect to foreign trade, as also to our home trade.

As to foreign trade, there needs little to be said. The trading nations of Europe were all afraid of us; no port of France, or Holland, or Spain, or Italy would admit our ships or correspond with us; indeed we stood on ill terms with the Dutch, and were in a furious war with them, but though in a bad condition to fight abroad, who had such dreadful enemies to struggle with at home.

Our merchants were accordingly at a full stop; their ships could go nowhere—that is to say, to no place abroad; their manufactures and merchandise—that is to say, of our growth—would not be touched abroad. They were as much afraid of our goods as they were of our people…

Finally, one day, everything clears up and normalcy returns. I share this last passage because it is what we long for–and also because it contains the warning, which we are hearing from our own scientists, that diseases don’t necessarily leave for good:

But the mercy of God was greater to the rest than we had reason to expect; for the malignity (as I have said) of the distemper was spent, the contagion was exhausted, and also the winter weather came on apace, and the air was clear and cold, with sharp frosts; and this increasing still, most of those that had fallen sick recovered, and the health of the city began to return. There were indeed some returns of the distemper even in the month of December, and the bills increased near a hundred; but it went off again, and so in a short while things began to return to their own channel. And wonderful it was to see how populous the city was again all on a sudden, so that a stranger could not miss the numbers that were lost. Neither was there any miss of the inhabitants as to their dwellings—few or no empty houses were to be seen, or if there were some, there was no want of tenants for them.

And further on:

In the middle of their distress, when the condition of the city of London was so truly calamitous, just then it pleased God—as it were by His immediate hand to disarm this enemy; the poison was taken out of the sting. It was wonderful; even the physicians themselves were surprised at it. Wherever they visited they found their patients better; either they had sweated kindly, or the tumors were broke, or the carbuncles went down and the inflammations round them changed color, or the fever was gone, or the violent headache was assuaged, or some good symptom was in the case; so that in a few days everybody was recovering, whole families that were infected and down, that had ministers praying with them, and expected death every hour, were revived and healed, and none died at all out of them

I’m just hoping that most of us, in a few months time, will be able to say, along with the narrator,

A dreadful plague in London

In the year sixty-five,

Which swept an hundred thousand souls

Away; yet I alive!