Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share it with anyone else.

Tuesday

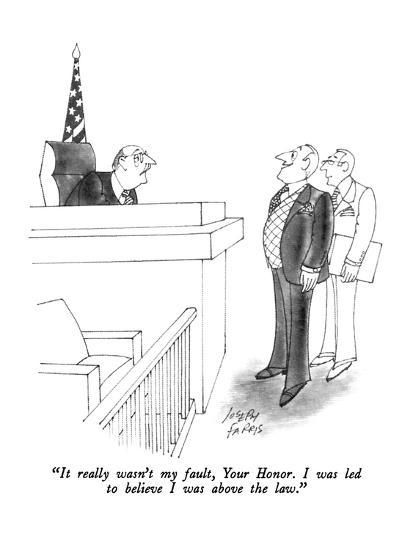

Today is the 227th anniversary of a momentous event that, over the past three years, has come to seem even more important than we previously realized. On September 19, 1796, President George Washington, announced that he would be stepping down from the presidency at the end of his term of office. His “Farewell Address” also warned the nation against political partisanship (!) and (particularly relevant given Russia’s continuing interference on Trump’s behalf) foreign influence in politics.

When George III heard of Washington’s plan to voluntarily relinquish power, he reportedly observed, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.”

We can appreciate that Washington, laudatory in so many other ways, also gave us a model for the peaceful transition of administrations. With the exception of 1860, when the election of Abraham Lincoln led to the secession of the Confederate states, Washington’s decision has served us well. That is, until January 6, 2021.

To honor Washington, I’m posting a Phillis Wheatley poem, written shortly before the American Revolution.

Wheatley, sold as a slave by a tribal chieftain in Senegal or the Gambia, ended up with the Wheatley family in Boston, who recognized her talents and encouraged her poetry. Not long after her book of poetry was published in London in 1773, the Wheatley family freed her. Her poem in praise of Washington was in turn praised by Washington, who wrote, “the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents.” He also invited her to visit him at his military camp, which she did.

The poem is written in heroic couplets, often used in the 18th century for epic poetry. (Alexander Pope, for instance, used the form for his translations of Homer.) When Wheatley invokes “Celestrial choir! Enthron’d in realms of light,” recent scholarship notes that she is probably invoking the African sun god of her childhood as well as the Greek muse that she encountered in her Latin and Greek education with the Wheatleys. The effect is to elevate America—Columbia—to mythic heights.

With the suffering colonies “involved in sorrows and the veil of night,” she calls upon Washington to unleash his armies as Aeolus, Greek god of the winds, releases his tempests. Calling the general “first in peace and honors,” she writes,

we demand

The grace and glory of thy martial band.

Fam’d for thy valour, for thy virtues more,

Hear every tongue thy guardian aid implore!

After all, since Washington has demonstrated his prowess in the French and Indian War (“When Gallic powers Columbia’s fury found”), America should be able to turn to him for defense against “whoever dares disgrace/ The land of freedom’s heaven-defended race!” The poem concludes with a call:

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the Goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! Be thine.

While Washington probably would have proceeded even without Wheatley’s injunction, such a poem probably enters somewhere into that decision-making equation. Perhaps it puts a little more steel in the spine at a time when one needs all the courage one can muster.

His Excellency General Washington

By Phillis Wheatley

Celestial choir! enthron’d in realms of light,

Columbia’s scenes of glorious toils I write.

While freedom’s cause her anxious breast alarms,

She flashes dreadful in refulgent arms.

See mother earth her offspring’s fate bemoan,

And nations gaze at scenes before unknown!

See the bright beams of heaven’s revolving light

Involved in sorrows and the veil of night!

The Goddess comes, she moves divinely fair,

Olive and laurel binds Her golden hair:

Wherever shines this native of the skies,

Unnumber’d charms and recent graces rise.

Muse! Bow propitious while my pen relates

How pour her armies through a thousand gates,

As when Eolus heaven’s fair face deforms,

Enwrapp’d in tempest and a night of storms;

Astonish’d ocean feels the wild uproar,

The refluent surges beat the sounding shore;

Or think as leaves in Autumn’s golden reign,

Such, and so many, moves the warrior’s train.

In bright array they seek the work of war,

Where high unfurl’d the ensign waves in air.

Shall I to Washington their praise recite?

Enough thou know’st them in the fields of fight.

Thee, first in peace and honors—we demand

The grace and glory of thy martial band.

Fam’d for thy valour, for thy virtues more,

Hear every tongue thy guardian aid implore!

One century scarce perform’d its destined round,

When Gallic powers Columbia’s fury found;

And so may you, whoever dares disgrace

The land of freedom’s heaven-defended race!

Fix’d are the eyes of nations on the scales,

For in their hopes Columbia’s arm prevails.

Anon Britannia droops the pensive head,

While round increase the rising hills of dead.

Ah! Cruel blindness to Columbia’s state!

Lament thy thirst of boundless power too late.

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the Goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! Be thine.

Further thought: Did Wheatley also have slavery in mind when she called for those who “disgrace the land of freedom’s heaven defended race”? There’s irony here in that Washington himself was a slaveowner. But contradictions aside, Wheatley did make subtle allusions to slavery in her poetry, such in an earlier poem that she directed to George III:

And may each clime with equal gladness see

A monarch’s smile can set his subjects free!