Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

On Monday, as I watched “the fearful bending of the knee” (Richard II) by the owners of the Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, I posted Oliver Wendell Holmes’s “Old Ironsides.” In the poem, the poet decries what he thought was the planned desecration of the fabled warship, the U.S.S. Constitution.

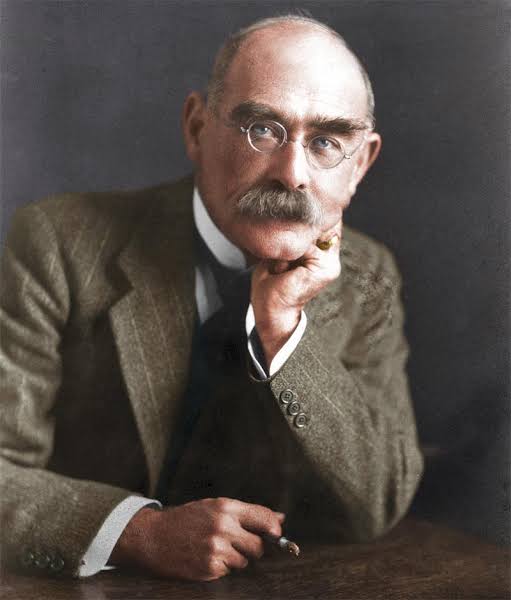

Dana Milbank, one of the many Washington Post columnists who protested owner Jeff Bezos’s decision to pull the Post’s endorsement of Kamala Harris in deference to Donald Trump, has asked us to nevertheless keep faith with the newspaper. In his argument, he draws on Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If.” More on that in a moment.

Although I have canceled subscriptions in the past, most notably the New York Times for its hatchet job on Hillary Clinton in 2016, I am swayed by the case Milbank makes.

He notes that Bezos has, before this, been a remarkably hands-off editor. And although the Post, like other major newspapers, has been guilty of sane-washing Trump, Bezos is no Rupert Murdoch or Elon Musk. Since he bought the newspaper in 2013, Milbank notes, it has won

18 Pulitzer prices, including for its coverage of the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection, its exposure of Trump’s phony charitable work, revelations about secret surveillance at the National Security Agency and lapses at the Secret Service, and its reporting on police shootings, poverty, abortion, racial justice and climate change. Just two weeks ago, The Post won two Loeb Awards, the top prize in business journalism, including for my colleagues Heather Long and Sergio Peçanha’s editorials on post-pandemic revival of America’s downtowns. All three finalists in the commentary category were from The Post.

The problem is that such journalism is expensive. The paper lost $77 million last year, which only a billionaire like Bezos can shrug off.

The question is how the Post will behave in the future, and here’s where Kipling comes in. Milbank draws on one of Kipling’s lines about reliance in his inspiring poem “If”:

Those of us working in the news business for the last quarter century know what it’s like to “watch the things you gave your life to, broken/ And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools” as Kipling put it. For all its flaws, The Post is still one of the strongest voices for preserving our democratic freedoms.

Incidentally, “If” has other good advice for us in the final week of this election season. When you see people panicking and disagreeing, when you see political actors lying and hating, consider the following:

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you,

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise…

And how about this for campaign volunteers pushing themselves to the limit to save democracy:

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

And then there’s this rousing conclusion, which could use a gender addition but is otherwise perfect for the occasion:

If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with Kings—nor lose the common touch,

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you,

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!

Returning to the subject at hand, Milbank gives the go-ahead for canceling subscriptions if the Post does indeed become broken beyond repair. As he puts it,

If this turns out to be the beginning of a crackdown on our journalistic integrity — if journalists are ordered to pull their punches, called off sensitive stories or fired for doing their jobs — my colleagues and I will be leading the calls for Post readers to cancel their subscriptions, and we’ll be resigning en masse.

But it’s not that broken yet, even with the sane-washing we have witnessed, and good pro-democratic work is still being done. Canceling subscriptions will not address the bigger issue, which is that Trump is trying to turn us into another Russia, where oligarchs kowtow to the strongman in charge. If we get to that point, we’ll have bigger issues than a pulled endorsement.

In the meantime, I leave you with these final sentiments, also drawn from the poem and which conclude with the line Milbank shares:

If you can dream—and not make dreams your master;

If you can think—and not make thoughts your aim;

If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same;

If you can bear to hear the truth you’ve spoken

Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools,

Or watch the things you gave your life to, broken,

And stoop and build ’em up with worn-out tools…

When it comes to deciding who to vote for, this is no time for choosing the perfect (“dreams”) over the good (Voltaire) or letting ideology–“thoughts”–triumph over practical reality. Knaves, helped along by AI and Russian bots, are twisting the truth non-stop, and sometimes it may feel that democracy’s traditional tools have been broken. But whether or not we prevail in this election, the fight will go on. No Triumph and no Disaster is ever the final word.