Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Sunday

Each year, as a Lenten discipline, I take up a challenging reading project that I believe will deepen me spiritually. As poet priest Malcolm Guite observes, Lent is a good time for poetry since, through poems, we can arrive at “clarification of who we are, how we pray, how we journey through our lives with God and how he comes to journey with us.” Lent, Guite says,

is a time set aside to re-orient ourselves, to clarify our minds, to slow down, recover from distraction, to focus on the values of God’s Kingdom and on the value he has set on us and on our neighbours. There are a number of distinctive ways in which poetry can help us do that…

Guite then quotes Seamus Heaney as to how poetry offers a “a glimpse and a clarification,” and he quotes Coleridge about what he and Wordsworth were hoping to offer through their poetry, which was

awakening the mind’s attention to the lethargy of custom, and directing it to the loveliness and the wonders of the world before us; an inexhaustible treasure, but for which, in consequence of the film of familiarity and selfish solicitude, we have eyes, yet see not, ears that hear not, and hearts that neither feel nor understand.

An article I blogged on 13 years ago, by Marilyn Chandler McEntyre, compares reading literature carefully to the ancient practice of lectio divina, which involves “reading Scripture slowly, listening for the word or phrase that speaks to you, pausing to consider prayerfully the gift being offered in those words for this moment.” Reading this way, she says,

can change the way we listen to the most ordinary conversation. It can become a habit of mind. It can help us locate what is nourishing and helpful in any words that come our way—especially in what poet Matthew Arnold called “the best that has been thought and said”—and it can equip us with a personal repertoire of sentences, phrases, and single words that serve us as touchstones or talismans when we need them.

And:

In each reading of a book or poem or play, we may be addressed in new ways, depending on what we need from it, even if we are not fully aware of those needs. The skill of good reading is not only to notice what we notice, but also to allow ourselves to be addressed. To take it personally. To ask, even as we read secular texts, that the Holy Spirit enable us to receive whatever gift is there for our growth and our use. What we hope for most is that as we make our way through a wilderness of printed, spoken, and electronically transmitted words, we will continue to glean what will help us navigate wisely and kindly—and also wittily—a world in which competing discourses can so easily confuse us in seeking truth and entice us falsely.

Over the years, for my Lenten reading I’ve read Proust’s Swann’s Way, Book I of Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene, the poetry of George Herbert, John Milton’s Paradise Regained, the religious poems of T. S. Eliot, and Dante’s Paradiso.

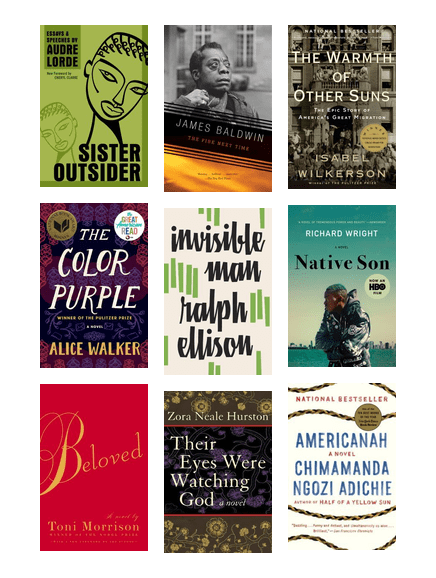

This year I’ve decided to read works by African American authors that I should have read years ago, along with Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, which has been made into a movie. (Julia and I watched it in a theater a week ago.) By seeing caste rather than racism as America’s underlying problem, Wilkerson is able to connect America-style discrimination with what has happened to marginalized groups in other societies and other times, such as the Dalits or “untouchables” in India and the Jews in Nazi Germany.

I’m eager to see how thinking of racism as a caste will influence my reading of Richard Wright’s Native Son, Laraine Hansberry’s Raisin in the Sun, James Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk, Jamaica Kincaid’s Annie John, and Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad, all works which I should have read but for one reason or another haven’t. And of course I’ll read Caste as well.

In a recent column on why Trump is so popular amongst the white working class, New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait recently made a compelling case that other factors than the economy are the determining factor. After all, these voters were ravaged by the Trump presidency and are benefiting from the Biden economy. Chait writes that

delivering broadly shared prosperity for the working class has done nothing so far to reduce the appeal of Trumpism. His appeal is not born of desperation or despair. Whatever alchemy produced the Trump cult, money alone will not dispel it.

Perhaps America’s caste system is the explanatory alchemy. Creative writers who have been victimized by that system often have the deepest insight into it, understanding best how it has worked into the fibers of our being. Understanding the dynamics of caste may allow me to be a more articulate critic.