Wednesday

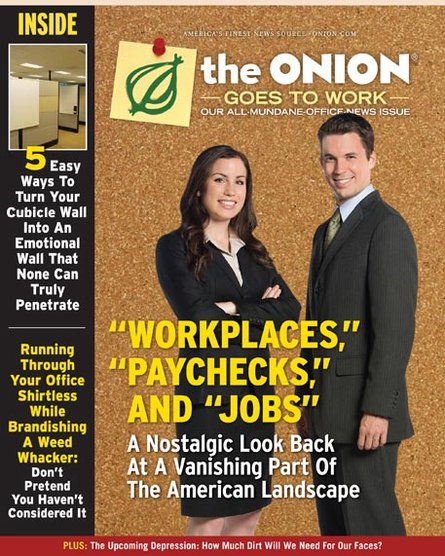

From time to time, I share material that appears on the twitter feed of my college professor son. Tobias Wilson-Bates, who teaches English at Georgia Gwinnett College, is always stimulating and always fun. (I know I’m prejudiced but others find him so as well.) Recently, he promised that, if his twitter followers reached 7000—stratospheric for a twitter feed that focuses on 18th and 19th century British literature—he would give us his top ten British poems from 1800-1900.

Having attained the 7000-follower mark yesterday, he shared his list. After apologizing for not including other traditions on his list (American, Australian, Indian), and sounding relieved that the century mark meant that he could exclude Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads (which contains Tintern Abbey, “Kublai Khan,”and Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner), he came up with the following list, along with his rationale for choosing it. I’ve included the excerpts he attaches from the less familiar poems:

10. I’m immediately going to cheat with a tie at 10. Light verse often doesn’t make these kind of lists but “The Owl and the Pussycat” (1870) by Edward Lear and “Jabberwocky” (1871) by Lewis Carroll are two of the most enduring and mind-expanding poems of the century.

9. A poet mostly remembered as a novelist, who I always read instead as a poet. [After all, Emily Bronte] once wrote a prose poem so long that they called it a novel instead. Emily Bronte’s “No Coward Soul is Mine” (1846). A poem that tears at the fabric of life and meaning. Incredible.

No coward soul is mine

No trembler in the world’s storm-troubled sphere

I see Heaven’s glories shine

And Faith shines equal arming me from Fear

O God within my breast

Almighty ever-present Deity

Life, that in me hast rest,

As I Undying Life, have power in Thee

Vain are the thousand creeds

That move men’s hearts, unutterably vain,

Worthless as withered weeds

Or idlest froth amid the boundless main

To waken doubt in one

Holding so fast by thy infinity,

So surely anchored on

The steadfast rock of Immortality.

With wide-embracing love

Thy spirit animates eternal years

Pervades and broods above,

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates and rears

Though earth and moon were gone

And suns and universes ceased to be

And Thou wert left alone

Every Existence would exist in thee

There is not room for Death

Nor atom that his might could render void

Since thou art Being and Breath

And what thou art may never be destroyed.

8. George Meredith’s Modern Love (1862) 16 sonnets to grow old and die with. Lines that feel like they have left lacerations across my skin.

Sonnet 1

By this he knew she wept with waking eyes:

That, at his hand’s light quiver by her head,

The strange low sobs that shook their common bed

Were called into her with a sharp surprise,

And strangled mute, like little gaping snakes,

Dreadfully venomous to him. She lay

Stone-still, and the long darkness flowed away

With muffled pulses. Then, as midnight makes

Her giant heart of Memory and Tears

Drink the pale drug of silence, and so beat

Sleep’s heavy measure, they from head to feet

Were moveless, looking through their dead black years,

By vain regret scrawled over the blank wall.

Like sculptured effigies they might be seen

Upon their marriage-tomb, the sword between;

Each wishing for the sword that severs all.

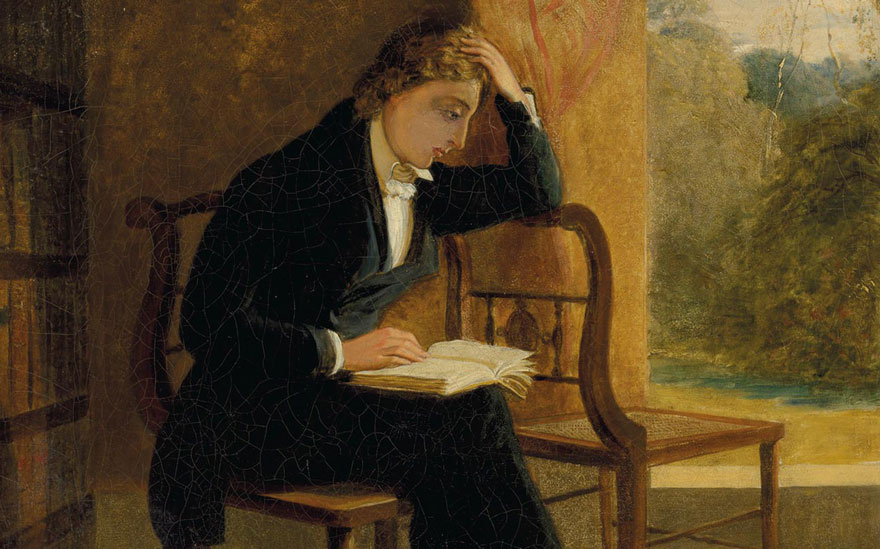

7. I forgot another caveat that poets only get to appear once on the list, so sorry in advance to Keats (obvs) At 7, is this [Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” 1842] even a poem? No idea but it’s may be the most teachable and memorable poetic character of the century.

6. Recent discourse has gotten me back into wanting to reignite my research on a poem that got packaged w/ a paper cover bc it sold as pornography and by some estimates circulated 500,000 copies when that was an INSANE number. Byron’s pervert epic (or epic perv) Don Juan (1819)

5. It’s important w these lists to remember that the 20th century has been SHAMELESSLY stealing 19th century poets for years. Yeats gets remembered for 2nd Coming, but “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” is arguably a much better poem.

4. ok, look, lists are hard, and I am only a baby who just learned how to read. Gerard Manley Hopkins could have at least 4 poems on this list (Windhover, Pied Beauty, Spring & Fall etc), but I personally have never recovered from encountering As Kingfisher’s Catch Fire (1889):

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.

I say móre: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: thát keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is —

Chríst — for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

3. Same with this poet. Odes, Autumn, Beauty, Eve, Chapman’s Homer. Stunning poem after stunning poem. But Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819) feels like the most POEM poem I have ever read. Surreal, shocking, lovely nightmare of a meditation.

First stanza:

Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

2. Ok, poems are weird, twisty objects that we encounter in our trauma and that give voice to our joy/suffering at existence. I am crying now just reading Shelley’s ‘Adonais’ (1821) again. I don’t think anyone would put it here over Ozymandias, but such is life.

From Stanza LXII

He is made one with Nature: there is heard

His voice in all her music, from the moan

Of thunder, to the song of night’s sweet bird;

He is a presence to be felt and know

In darkness and in light, from herb and stone…

1. If you have not read this poem, log off and read it. If you have read it and are in a position to make others read it, please don’t hesitate to do so. Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market (1862) is the poem of the century. Funny, scary, sensuous, dazzling shape of a dream.

And then come Toby’s apologies:

OK OBVIOUS APOLOGIES TO AURORA LEIGH and IN MEMORIAM and THE PRELUDE and DOVER BEACH and DARKLING THRUSH and the list goes on and on and on and on. An impossible task. Please make your own lists!

Actually, the only poem omitted from the list that I think he needs to apologize for—given that it is also omitted from the apologies—is Wordsworth’s Intimations of Immortality. But okay, such lists are hard. They may be most interesting in what they tell us about the list maker.

For instance, when noting how he had to drop Lyrical Ballads from the list, Toby noted that his favorite poem from the collection is not Ancient Mariner or Tintern Abbey but “We Are Seven.” I explore here why the poem means so much to Toby, which has to do with his oldest brother, who died in a freak drowning accident 22 years ago.

Likewise, the stanza Toby chose from Shelley’s Adonais is the passage on Justin’s tombstone.

Top ten lists are also like love notes, telling our favorite poems how much we cherish them. And they work as invitations for others to express their own gratitude.