Thursday

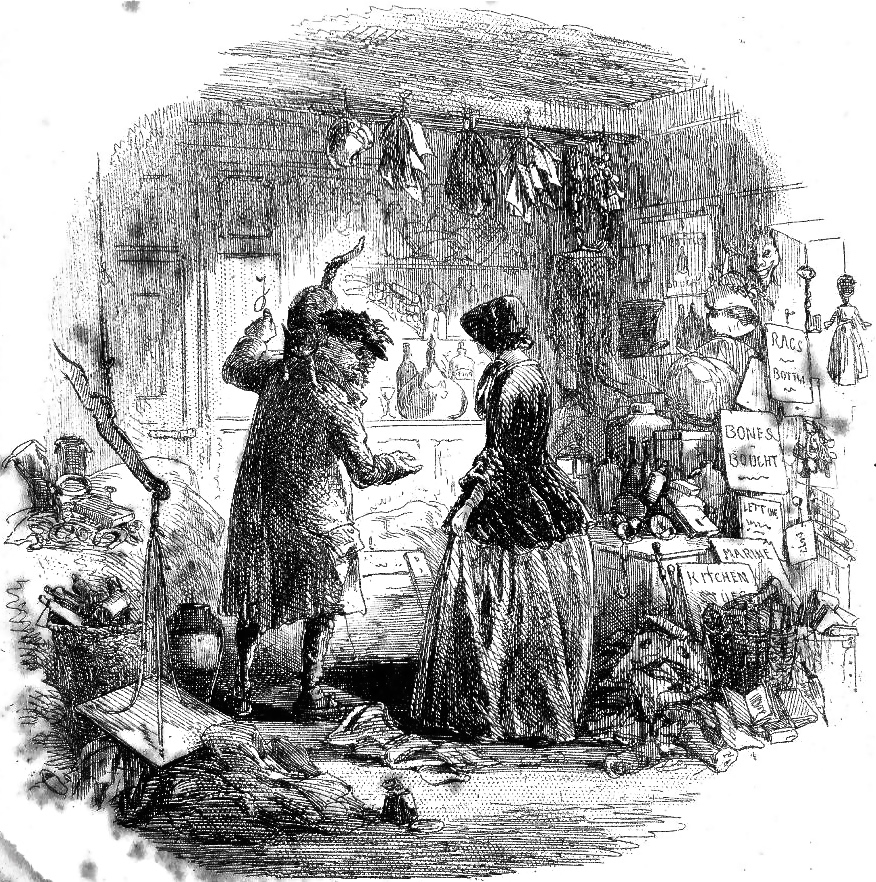

As relatives show up for my mother’s Saturday memorial service, we are sifting through masses of correspondence, financial records, income tax filings, old newspaper clippings, useless remote controls, outmoded technology (such as slide projectors, light tables, and manual typewriters), and tons of flotsam and jetsam. As we sort through it, keeping some and jettisoning some, I think of Krook’s Rag and Bones Shop in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. Here’s a description:

In one part of the window was a picture of a red paper mill at which a cart was unloading a quantity of sacks of old rags. In another was the inscription BONES BOUGHT. In another, KITCHEN-STUFF BOUGHT. In another, OLD IRON BOUGHT. In another, WASTE-PAPER BOUGHT. In another, LADIES’ AND GENTLEMEN’S WARDROBES BOUGHT. Everything seemed to be bought and nothing to be sold there. In all parts of the window were quantities of dirty bottles—blacking bottles, medicine bottles, ginger-beer and soda-water bottles, pickle bottles, wine bottles, ink bottles; I am reminded by mentioning the latter that the shop had in several little particulars the air of being in a legal neighbourhood and of being, as it were, a dirty hanger-on and disowned relation of the law. There were a great many ink bottles. There was a little tottering bench of shabby old volumes outside the door, labelled “Law Books, all at 9d.” Some of the inscriptions I have enumerated were written in law-hand, like the papers I had seen in Kenge and Carboy’s office and the letters I had so long received from the firm. Among them was one, in the same writing, having nothing to do with the business of the shop, but announcing that a respectable man aged forty-five wanted engrossing or copying to execute with neatness and dispatch: Address to Nemo, care of Mr. Krook, within. There were several second-hand bags, blue and red, hanging up. A little way within the shop-door lay heaps of old crackled parchment scrolls and discoloured and dog’s-eared law-papers. I could have fancied that all the rusty keys, of which there must have been hundreds huddled together as old iron, had once belonged to doors of rooms or strong chests in lawyers’ offices. The litter of rags tumbled partly into and partly out of a one-legged wooden scale, hanging without any counterpoise from a beam, might have been counsellors’ bands and gowns torn up. One had only to fancy, as Richard whispered to Ada and me while we all stood looking in, that yonder bones in a corner, piled together and picked very clean, were the bones of clients, to make the picture complete.

Apparently rag and bone men once literally collected bones, which were boiled down for glue, but the expression came to mean unwanted household items. While my mother differed from Krook in that she was a tidy lady—her checkbooks dating back to the early 1980s are all neatly filed—she was reluctant to throw anything away. Now her children are faced with doing so.

Chaotic though Krook’s Rag and Bone Shop may be, it has a copy of the most recent will in the Jarndyce v Jarndyce case. In other words, the nightmarish lawsuit that has ruined the lives of countless individuals could have been solved instantly had this actual will not been buried under mounds of stuff.

In our own searching, we have unearthed correspondence that my father had with Bill Moyer, Pete Seeger, Robert Penn Warren, poet Elizabeth Alexander, and others. We too have struck gold amidst all the junk.

It’s nothing that will have an impact on anything. But then, neither does the long-lost Jarndyce will. That’s because, by the time it’s brought to court to clear everything up, the case has just ended, legal legal expenses having exhausted all the money tied up in the lawsuit.

I’m not sure what the moral is here other than that the living should focus on living rather than be ruled by the dead hand of the past. My mother’s hand wasn’t heavy but we’re committed to throwing away anything that is of no use to anyone. Krook, by having dwelt so long in the junk of the past, spontaneously combusts—Dickens controversially insisted this was scientifically possible—and we’re determined not to let that happen to us.