Monday

I report today on a wonderful experience I had last this past Thursday teaching the card game Speculation to 60 Vanderbilt Library patrons. The characters in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park play the game and Austen herself was a fan. After putting together my opening remarks, I better understood why.

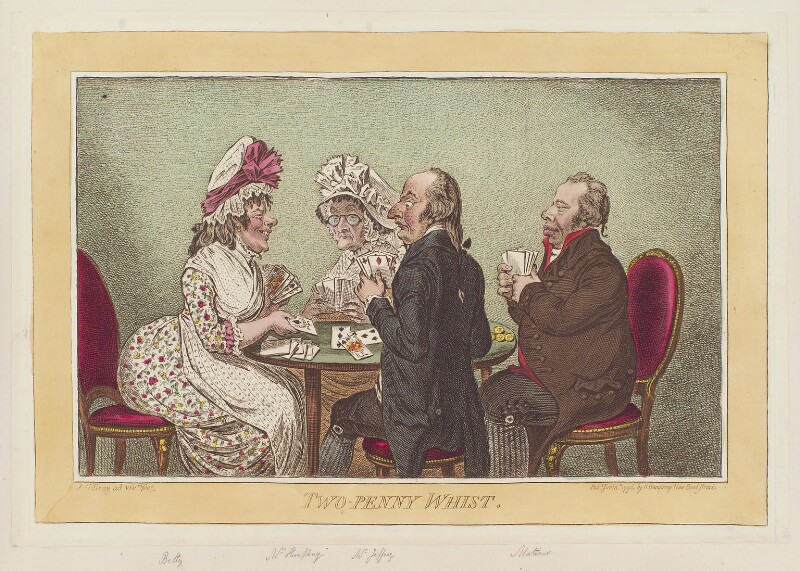

First, let me set the Vanderbilt scene. The occasion was arranged to publicize the library’s impressive acquisition of the U.S. Playing Card Association’s collection of card-related documents, including a 15th century sermon railing against Tarot. Last year a speaker talked about the history of Hoyle’s Book of Games and then taught attendees how to play whist. I was invited this year to speak on card playing in Jane Austen and to teach Speculation. I may be back next year to talk about and teach Ombre, the card game played in Alexander Pope’s Rape of the Lock.

For the Thursday evening session, players were gathered around tables in groups of five or six. Each table had two packs of cards—one to be shuffled while the other was being dealt—along with small bags containing 40 wooden coins. In the center a placard announced the prizes that could be won—“library swag,” as Head Librarian Valerie Hotchkiss called them—along with a copy of the rules.

I observed in opening that, lovely though the setting was, super snob Mrs. Elton of Emma would have found fault. Here’s how she judges a card gathering she attends and what she herself plans in response:

She was a little shocked at the want of two drawing rooms, at the poor attempt at rout-cakes, and there being no ice in the Highbury card-parties. Mrs. Bates, Mrs. Perry, Mrs. Goddard and others, were a good deal behindhand in knowledge of the world, but she would soon shew them how everything ought to be arranged. In the course of the spring she must return their civilities by one very superior party—in which her card-tables should be set out with their separate candles and unbroken packs in the true style—and more waiters engaged for the evening than their own establishment could furnish, to carry round the refreshments at exactly the proper hour, and in the proper order.

I noted with regret that some of our card packs had already been opened and that our buffet arrangement meant that waiters were not carrying around refreshments “at exactly the proper hour, and in the proper order.”

Turning my attention to card games, I observed that literature has often used cards for thematic purposes. Alluding to last year’s session on whist, I reflected on why Jules Verne has Phileas Fogg play it in Around the World in 80 Days. What better way to capture an effete but steely-spined Englishman than by depicting him calmly taking tricks as he circumnavigates the globe. The image brings together the decorous drawing room and Britain’s colonial expansion.

Austen definitely uses card games for thematic effect, as I noted in a post from last week. None receives such thorough treatment as Speculation, which is why we selected it. We know from a letter to Cassandra about their nephews that Austen herself enjoyed the game:

Our evening was equally agreeable in its way. I introduced speculation, and it was so much approved that we hardly knew how to leave off.

In the game, the players ante into a pot and then are dealt three cards, all facedown. (I’ve blogged on the rules here.) A final card is then dealt face-up, becoming the trump card. One by one the players reveal their cards, with the highest card in that suit winning the pot.

Players speculate in various ways. They may offer to buy the card from the dealer if they think it will be the final winner. The player holding the highest card at any particular moment may buy facedown cards from other players to make sure that this particular trump card holds. Other speculative purchases are possible as well.

I noted in my talk that speculation was in the air during the Napoleonic wars, which is when Austen wrote her novels. Historian Jenny Uglow notes that national borrowing primed the pump, benefitting

army contractors, who provided massive quantities of tents, knapsacks, canteens, uniforms, shoes, muskets, gunpowder, ships, maps, fortifications, meat, and biscuit; bankers and speculators, who funded the supplies as well as subsidies to Britain’s allies…; [and] revenue agents, who collected the wide variety of taxes imposed to finance the wars…

Seen through the lens of the card game, all of Austen’s major novels can be seen as featuring Speculation plots or subplots. For instance:

–In Northanger Abbey, Isabel Thorpe trades in a certain high card (William Morland) for the possibility of a higher one (Captain Frederick Tilney) but ends up with nothing;

–The opposite occurs in Sense and Sensibility. Willoughby thinks he must trade in Marianne, whom he loves, for Miss Grey to ensure his inheritance from Mrs. Smith of Allenham. The marriage is unhappy and he later learns it was a needless sacrifice: had he played his cards right, he could have gotten both Allenham and Marianne;

–Lucy Steele proves more successful, trading in the disinherited Edward Ferrars for his brother Robert;

–in Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth passes on Mr. Collins (Charlotte Lucas jumps on him) and is vindicated when she lands Darcy;

–her sister Lydia, a reckless gambler, makes a bad bet and is only saved from ruin by the intervention of others;

–Mary Crawford reveals her hand in Mansfield Park by showing she wants Robert Bertram to die so that the man she is set on (younger brother Edmund) will be a squire rather than a rector. Like Isabel Thorpe, she aims too high and ends up with nothing;

–Maria Bertram grabs a sure thing (Rushworth) but is so unsatisfied with him that she ruins her life. Her sister, meanwhile, grabs what she knows she can get (Yates) but only after she realizes a higher card is out of reach (Henry Crawford);

–Fanny Price passes up a certain winner (Crawford) and is rewarded with higher one (Edmund);

–Emma, playing with someone else’s money, advises Harriet to pass up a sure thing (Roger Martin) and speculate on first Mr. Elton and then Frank Churchill. Unfortunately, Emma so infuses Harriet with speculative fever that the young woman goes all in and targets Knightley—and nearly ends up with nothing at all;

–Finally, in Persuasion a young Anne Elliot should marry a speculator who, although poor, is confident in his powers. Wentworth is sure he can parlay “a ship not fit to be employed” into a fortune and in fact does. In other words, Anne wants to speculate but is persuaded by well-meaning but cautious friends not to. She later declares she would never counsel a young friend to hold back.

Like Elizabeth Bennet and Fanny Price, however, Anne gambles on everything or nothing, passing up Robert Musgrove, Benwick, and Mr. Elliot and then landing Wentworth after all. The reason these three heroines receive the payoffs they desire is that they step beyond the cash nexus altogether. Love and character count more than money. In other words, they are not moved by mere acquisition.

In this context, it’s useful to recall the scene where Crawford coaches Fanny in how to play Speculation. While she picks up the game quickly, she can’t grasp its predatory dimensions:

…for though it was impossible for Fanny not to feel herself mistress of the rules of the game in three minutes, [Crawford] had yet to inspirit her play, sharpen her avarice, and harden her heart.

In short, Speculation reenacts a pressing drama of the age–just as, say, the board game Monopoly did for several decades in America.

In the various Mansfield Park characters, we see the full range of playing styles to be found amongst Speculation players. The main lesson: When you gamble on the future, be bold but not reckless. Take calculated risks, going big but not too big. Here are the six card players and their approaches to the game:

–Poor but ambitious William Price will succeed only if he takes risks, plays a bold game, and does not hesitate to take advantage of others–who in this case include his accommodating sister;

–Fanny Price, on the other hand, allows others to exploit her, at least when it comes to cards;

–Henry Crawford, very manipulative, claims he wants to help others and to some extent does so. But given that he uses his position as coach to get close to Fanny, everything he does must be regard skeptically;

–Lady Bertram is clueless and depends on others to take care of her;

–Mary Crawford plays emotionally and recklessly, sometimes paying more for a card than the pot is worth;

–Edmund Bertram, as far as we can tell, plays a balanced game. The outcome doesn’t mean as much to him as to the less privileged William Price, which probably means he doesn’t haggle as much.

What did I learn from the evening? I better understood why Austen enjoyed Speculation so much. It’s a noisy game with a lot of personal interaction, as players haggle over card prices and cheer or moan as a card wins or loses. In the different groups it became clear who were the Fanny and William Prices, the Henry and Mary Crawfords, the two Bertrams.

I saw also how Speculation allows a lot of side-talk. The game doesn’t require as much concentration as, say, bridge. In that way, it serves Austen’s artistic purposes: characters can have important conversations without interrupting the flow of the action.

Above all, Speculation offers people a wonderful way to come together and spend an evening.