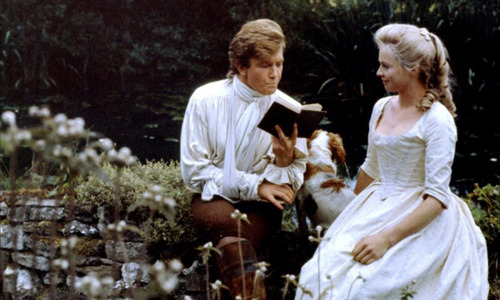

Today on “Recovered Blog Posts” I reprint a lost essay that originally appeared on November 4, 2009. As it turns out, it could have been written yesterday, which is when I wrapped up my most recent teaching of Tom Jones.

Yesterday my 18th Century Couples Comedy class concluded our discussion of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones. We spent a lot of time discussing its popularity with youthful readers in the 18th century, an idea I owe to J. Paul Hunter, my dissertation director at Emory University. Paul explores the issue in Before Novels: The Cultural Contexts of 18th Century English Fiction.

I’ve mentioned several times in recent posts how moralists attacked Tom Jones for corrupting young people (for instance, here). I assume they were most disturbed by Tom’s sexual escapades and the novel’s bawdy humor, but I wonder if some of their fire was aimed at Fielding’s satiric portrayals of parents and teachers, most of whom are heavy-handed and hypocritical. To add insult to injury, the student that these teachers hold up as exemplary is young Blifil, the book’s villain. Blifil always tells them exactly what they want to hear.

In a spirited discussion, my class demonstrated that novels are indeed powerful vehicles for true moral instruction. I asked them to put Tom on trial and render a verdict. They were to decide whether Sophia should forgive him and marry him, even though, at different points, he makes love to three different women, even while professing love for her.

A moral debate ensued in which the students weighed character, mitigating circumstances, the competing claims of justice and mercy, and the like. They used their brains, their moral compasses, their knowledge of life, and their ability to explore ideas in a communal setting.

In doing so they were aided by the modeling Fielding himself does in the book, both as an intrusive narrator and through the figure of Squire Allworthy. As narrator, Fielding is constantly discussing how to render judgment, both on the characters and on himself as the author. Fielding was a judge and knew that simple prescriptions are not always enough to guide us. For one thing, appearances can be deceiving and even the best intentioned make mistakes.

Squire Allworthy is an example. Although a good and moral man, as justice of the peace Allworthy hands down some faulty sentences. Occasionally innocent people (Tom, Partridge) pay a heavy price. Allworthy speaks for the author, however, when he says that, in the end, prudence and religion, our practical and our moral compass, will get us through life.

But for young people to develop those compasses, it’s not enough for stern teachers (like Thwakum) to beat values into them, nor for parental figures (like Lady Western) to deliver long and tiresome lectures about doing what they are told. Instead, there needs to be a constant give-and-take, an open dialogue, between young people and old.

We see this at the end where Tom and Allworthy are figuring out how to mete out justice. Allworthy is so appalled at Blifil that he is prepared to cast him out penniless, but Tom counsels mercy and Blifil receives a small sum. On the other hand, Allworthy recognizes that mercy without justice can become flaccid. When Tom learns that Black George, a man he has repeatedly helped, has stolen money from him, he argues the man’s poverty as a mitigating circumstance. Allworthy will have none of it:

“Child,” cries Allworthy, “you carry this forgiving temper too far. Such mistaken mercy is not only weakness, but borders on injustice, and is very pernicious to society, as it encourages vice. The dishonesty of this fellow I might, perhaps, have pardoned, but never his ingratitude. And give me leave to say, when we suffer any temptation to atone for dishonesty itself, we are as candid and merciful as we ought to be; and so far I confess I have gone; for I have often pitied the fate of a highwayman, when I have been on the grand jury; and have more than once applied to the judge on the behalf of such as have had any mitigating circumstances in their case; but when dishonesty is attended with any blacker crime, such as cruelty, murder, ingratitude, or the like, compassion and forgiveness then become faults. I am convinced the fellow is a villain, and he shall be punished; at least as far as I can punish him.”

Young and old must negotiate the world together. Tom needs Allworthy’s experience and broader perspective, but Allworthy cannot entirely understand the complicated new world that Tom is facing. The city in which Tom loses his way and which is England’s future is a far cry from Allworthy’s rural estate. Fielding shows us how they can collaborate to create a wholesome society.

I learned from my students that most were raised on such a model, with parents both guiding them and respecting and even learning from their experiences. While sometimes parents must put their foot down, more often they need to engage their adolescent children in open discussions. They need to share stories and sort out the issues together

Julia and I shared our own stories with our sons and invited them to share theirs. In addition, we read to them every night of their childhoods. When the occasion arose, we talked about the characters and the plots.

As a result, we now have two grown men who are able, when facing life’s pressures, to step back, examine the situation as though they were reflecting upon a story, and assess their options. Sometimes they even see parallels with fictional stories they have encountered, which gives them an extra degree of clarity and meaning.

Fielding saw this potential in the novel when the genre was in its infancy. At a time when moralists argued for a Thwackum approach, Fielding braved considerable criticism to chart a new way.