Friday

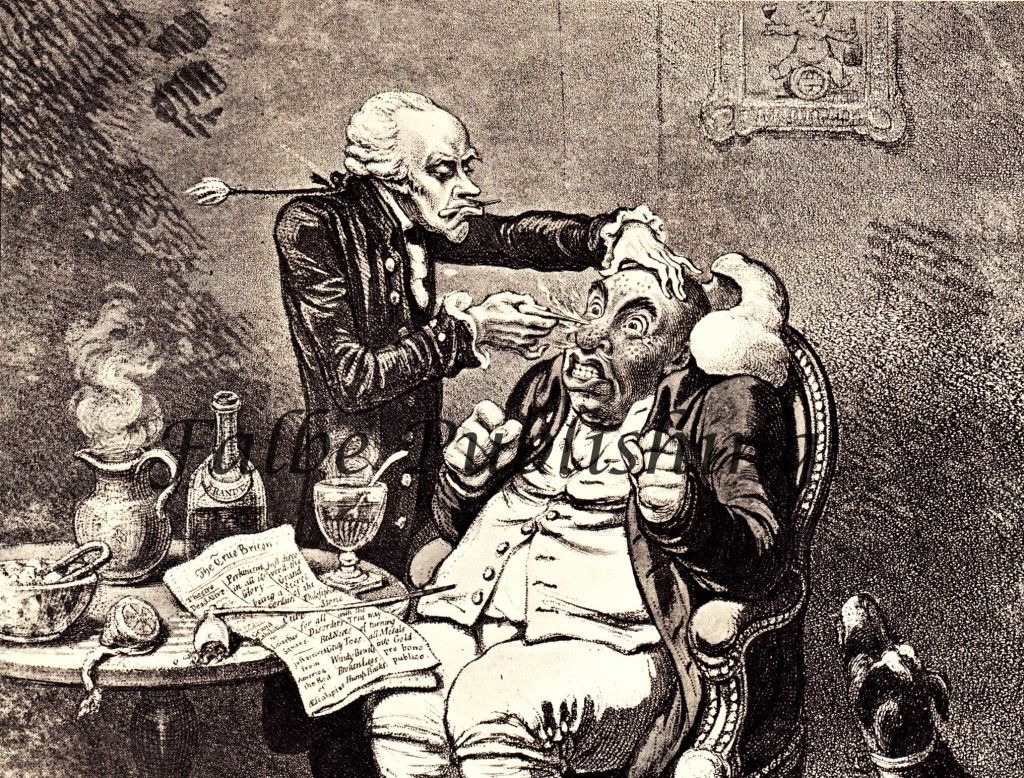

Given our many advances in medicine since the 18th century, I never would have thought that Henry Fielding’s delicious jabs at doctors in Tom Jones would be relevant again. And yet, here we are, with Donald Trump playing doctor in the face of a raging pandemic while denigrating leading epidemiologists and the Center for Disease Control.

Add in his choice of neuroradiologist Scott Atlas as chief medical consultant—a man who wants the disease to go unchecked in the uncertain hope that Americans will develop herd immunity (those who don’t die, that is)—and Fielding’s satiric pen appears all too necessary.

Actually, there’s one scenario where Fielding might praise Atlas for advocating non-action. That’s only because Fielding was justifiably suspicious of the medicines of his time, however. When they were the equivalent of Trump’s bleach cure, then the maxim that concludes the following passage would indeed be the better course:

There is nothing more unjust than the vulgar opinion, by which physicians are misrepresented, as friends to death. On the contrary, I believe, if the number of those who recover by physic could be opposed to that of the martyrs to it, the former would rather exceed the latter. Nay, some are so cautious on this head, that, to avoid a possibility of killing the patient, they abstain from all methods of curing, and prescribe nothing but what can neither do good nor harm. I have heard some of these, with great gravity, deliver it as a maxim, “That Nature should be left to do her own work, while the physician stands by as it were to clap her on the back, and encourage her when she doth well.”

Atlas, however, is more like the doctor who, upon attending an injured Tom, who lets his personal interests guide his medical practice. In this case, he dances to the tune of Tom’s landlady:

“All I can say at present is, that it is well I was called as I was, and perhaps it would have been better if I had been called sooner. I will see him again early in the morning; and in the meantime let him be kept extremely quiet, and drink liberally of water-gruel.”—“Won’t you allow him sack-whey?” said the landlady.—“Ay, ay, sack-whey,” cries the doctor, “if you will, provided it be very small.”—“And a little chicken broth too?” added she.—“Yes, yes, chicken broth,” said the doctor, “is very good.”—“Mayn’t I make him some jellies too?” said the landlady.—“Ay, ay,” answered the doctor, “jellies are very good for wounds, for they promote cohesion.” And indeed it was lucky she had not named soup or high sauces, for the doctor would have complied, rather than have lost the custom of the house.

The doctor reminds me of those experts who have gone into contortions to accommodate Trump (Coronavirus Response Coordinator Deborah Birx and CDC Director Robert Redfield, for instance) rather than tell him and us the pure, unvarnished truth. Of course, when Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told America the facts last February, she was promptly sidelined.

Birx and Redfield, however, are souls of integrity compared to Scott Atlas. Other Fielding doctors that he resembles are those who, “at a loss how to apply that portion of time which it is usual and decent to remain for their fee,” engage in pointless medical disputation.

These doctors are attending to the villainous Captain Blifil, who has unexpectedly died. What follows is a blistering attack on the medical profession:

These two doctors, whom, to avoid any malicious applications, we shall distinguish by the names of Dr Y. and Dr Z., having felt his pulse; to wit, Dr Y. his right arm, and Dr Z. his left; both agreed that he was absolutely dead; but as to the distemper, or cause of his death, they differed; Dr Y. holding that he died of an apoplexy, and Dr Z. of an epilepsy.

Hence arose a dispute between the learned men, in which each delivered the reasons of their several opinions. These were of such equal force, that they served both to confirm either doctor in his own sentiments, and made not the least impression on his adversary.

To say the truth, every physician almost hath his favorite disease, to which he ascribes all the victories obtained over human nature. The gout, the rheumatism, the stone, the gravel, and the consumption, have all their several patrons in the faculty; and none more than the nervous fever, or the fever on the spirits. And here we may account for those disagreements in opinion, concerning the cause of a patient’s death, which sometimes occur, between the most learned of the college; and which have greatly surprised that part of the world who have been ignorant of the fact we have above asserted…

Unable to do anything for the captain, they seize instead upon his widow, where they prove equally useless:

This lady was now recovered of her fit, and, to use the common phrase, as well as could be expected for one in her condition. The doctors, therefore, all previous ceremonies being complied with, as this was a new patient, attended, according to desire, and laid hold on each of her hands, as they had before done on those of the corpse.

The case of the lady was in the other extreme from that of her husband: for as he was past all the assistance of physic, so in reality she required none.

So much for most 18th century doctors. Fielding gives us one, however, who provides advice that the United States should have followed:

[S]urely the gentlemen of the Aesculapian art are in the right in advising, that the moment the disease has entered at one door, the physician should be introduced at the other: what else is meant by that old adage, Venienti occurrite morbo? “Oppose a distemper at its first approach.” Thus the doctor and the disease meet in fair and equal conflict; whereas, by giving time to the latter, we often suffer him to fortify and entrench himself, like a French army; so that the learned gentleman finds it very difficult, and sometimes impossible, to come at the enemy. Nay, sometimes by gaining time the disease applies to the French military politics, and corrupts nature over to his side, and then all the powers of physic must arrive too late. Agreeable to these observations was, I remember, the complaint of the great Doctor Misaubin, who used very pathetically to lament the late applications which were made to his skill, saying, “Bygar, me believe my pation take me for de undertaker, for dey never send for me till de physicion have kill dem.”

If we had opposed Covid-19 early instead of allowing it to fortify and entrench itself, millions of sick and dead Americans would have escaped infection. While our doctors may not be mistaken for undertakers, far too many of them have been forced into the role of relatives and priests as patients die in isolation.

Scott Atlas would be the kind of physician Doctor Misaubin has in mind.