In recent days a number of commentators have attributed the shutdown to a tantrum by American racists, who wanted not only to defund Obamacare but to humiliate the president, for whom the law is his signature achievement. Two recent studies bolster the case for racism. I will supplement them with a Flannery O’Connor short story to elaborate how such racism works

According to an article in the Washington Post blog The Monkey Cage, researchers have discovered that Republicans from districts with high levels of racial resentment were the most likely to vote in favor of shutting down the government and defaulting on the country’s debts. The article is careful to add that race is probably not the only factor involved but insists that there is a correlation.

To be sure, these results do not imply that the shutdown was primarily driven by racial prejudice against the president. Indeed, Republican members’ own ideologies were the strongest predictor of how they voted on the shutdown. At the same time, though, the results suggest that the much publicized divisions within the Republican Party correspond to a divide in their constituents’ racial attitudes.

Racism would certainly help account for the “Obama derangement” that we have been witnessing over the past five years. To be sure, we saw America’s far right throw similar tantrums against the last Democratic president, who of course was white. But even those efforts—the non-scandals of Whitewater, Vince Foster, and Travelgate, the government shutdown, the attempt to impeach a man over an extramarital affair—pale in comparison to the sustained and unceasing attempts to humiliate and delegitimize our African American president.

As one who was raised in the segregated south—my family moved to southern Tennessee in 1954 when I was three—I am not altogether surprised that we are increasingly seeing outbreaks of neo-Confederate fervor (including wild threats of secession), attempts to restrict minority voting, and use of racist caricatures (sometimes overt, sometimes cloaking themselves as birtherism). Throughout my childhood I saw people, especially poor whites, using racial scapegoating as a way to bolster their own self-esteem.

Flannery O’Connor’s short story “The Artificial Nigger” understands the psychological dynamics involved. The story is about a grandfather, Mr. Head from rural Georgia, who takes his grandson Nelson on his first trip to Atlanta. At one point they wander into a black neighborhood and feel out of their depth:

Nelson’s skin began to prickle and they stepped along at a faster pace in order to leave the neighborhood as soon as possible. There were colored men in their undershirts standing in the doors and colored women rocking on the sagging porches. Colored children played m the gutters and stopped what they were doing to look at them. Before long they began to pass rows of stores with colored customers in them but they didn’t pause at the entrances of these. Black eyes in black faces were watching them from every direction.

A pivotal scene in the story occurs when Nelson accidentally knocks over a woman carrying groceries, causing her to call for the police. In a moment of Peter-like betrayal, the panicked Mr. Head pretends he doesn’t know his own grandson.

He has committed a crime that seems to be beyond forgiveness. His grandson won’t speak to him, and for all the grandfather knows, a permanent rift has opened between them:

The child was standing about ten feet away, his face bloodless under the gray hat. His eyes were triumphantly cold. There was no light in them, no feeling, no interest. He was merely there, a small figure, waiting. Home was nothing to him.

Mr. Head turned slowly. He felt he knew now what time would be like without seasons and what heat would be like without light and what man would be like without salvation. He didn’t care if he never made the train and if it had not been for what suddenly caught his attention, like a cry out of the gathering dusk, he might have forgotten there was a station to go to.

What saves the situation for him is a racist emblem found in one of the yards they are passing:

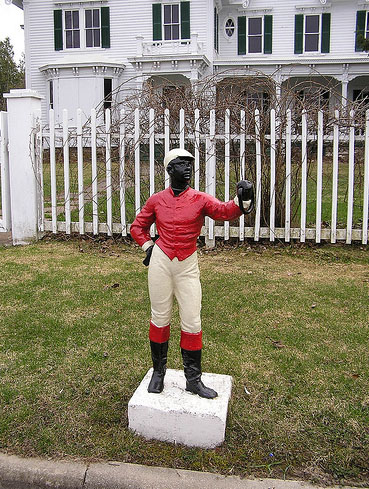

He had not walked five hundred yards down the road when he saw, within reach of him, the plaster figure of a Negro sitting bent over on a low yellow brick fence that curved around a wide lawn. The Negro was about Nelson’s size and he was pitched forward at an unsteady angle because the putty that held him to the wall had cracked. One of his eyes was entirely white and he held a piece of brown watermelon.

Mr. Head stood looking at him silently until Nelson stopped at a little distance. Then as the two of them stood there, Mr. Head breathed, “An artificial nigger!”

It was not possible to tell if the artificial Negro were meant to be young or old; he looked too miserable to be either. He was meant to look happy because his mouth was stretched up at the corners but the chipped eye and the angle he was cocked at gave him a wild look of misery instead.

“An artificial nigger!” Nelson repeated in Mr. Head’s exact tone.

The strangeness of the sight, which confirms for them how little they understand the world, unites them and they are reconciled. By the end of the story, Nelson is vowing never again to venture outside his comfort zone.

When one is feeling lost and confused, there is nothing like finding a social scapegoat to reorient oneself. I think this is how Obama hatred is working in America right now. To many white Americans, the country appears as unfamiliar—as colored—as Atlanta appears to Mr. Head and Nelson. Further stirring the discontent is the economic stagnation of the middle class. Like the Heads, many right wing Americans want to go home.

Home as it used to look, however, is no longer an option. The only thing they know for sure is they can look down on the man in the White House, whom the right wing media and any number of others have turned into a caricature. Obama is the point of stability that they can define themselves against.

As a shameless ideologue like Ted Cruz understands only too well, such Americans, in their fear, will countenance any action taken against him.