Thursday

I share today the latest draft of a chapter from my current book project Better Living through Literature: A 2500-Year-Old Debate. I’m still collecting feedback on how it can be improved.

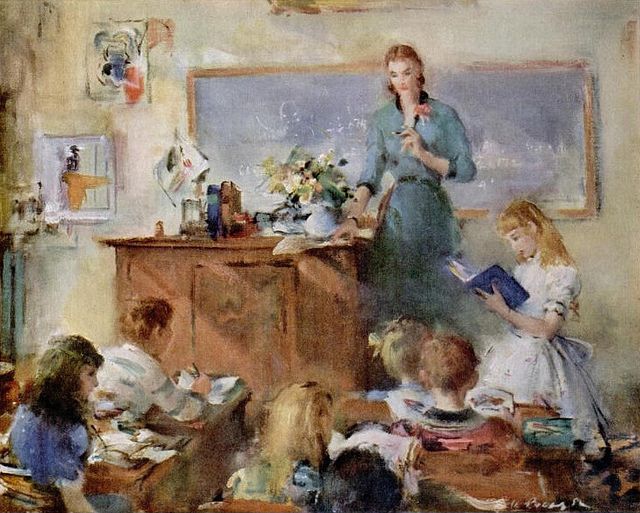

Once Matthew Arnold advocated teaching literature in school on the grounds that it will usher in a new epoch marked by “a national glow of life and thought,” teachers enter into our picture. In this vision they were to be the new missionaries, replacing religious figures in inculcating foundational social values. Teachers were to introduce students to poetry, the new sacred texts, and make sure they took away the proper lessons.

In his influential Literary Theory: An Introduction, Terry Eagleton does a historical survey of “the rise of English,” noting why people have wanted students to read and interpret literature. I’ve already cited Eagleton in my Marx-Engels chapter but turn to him here because his survey offers one of the best accounts of what people over the past 150 years have thought the study of literature should accomplish. While Eagleton’s Marxism shapes his account—he believes historical forces have been at work in literature’s evolution as a discipline—his summation is useful to non-Marxists as well.

That’s in part because Eagleton (b. 1943) isn’t doctrinaire in his beliefs. Born into a working-class Irish Catholic family with Irish Republican sympathies, he served as an altar boy at a local Carmelite convent as a boy and at one point considered becoming a priest. He studied literature at Cambridge under the noted Marxist scholar Raymond Williams and also edited a Catholic leftist periodical called Slant. Although a socialist, Eagleton, like his American counterpart Frederic Jameson, is suspicious of leftists who judge literary works by their class politics, calling such people “vulgar Marxists.” As we have seen, he has not hesitated to defend conservative artists such as Joseph Conrad, T.S. Eliot, and D.H. Lawrence. His same dislike of doctrinaire positions has led him, in later years, to go after atheists like Christopher Hitchens and evolutionary biology Richard Dawkins, accusing them of being just as narrow as the Christian fundamentalists they attack. Eagleton is a daunting opponent, in part because of his razor-sharp wit.

While English teachers haven’t traditionally seen themselves as political when they teach literature, Eagleton points out that 19th century school authorities, revealing the influence of Arnold, began stressing the importance of a literary education at precisely the point when working class men and women gained admittance into schools and universities. In other words, literary instruction had a political agenda from the beginning, which was to maintain the existing class and gender relations. About worker education Eagleton writes,

It is significant…that “English” as an academic subject was first institutionalized not in the Universities, but in the Mechanics’ Institutes, working men’s college and extension lecturing circuits. English was literally the poor man’s Classics—a way of providing a cheapish “liberal” education for those beyond the charmed circles of public school and Oxbridge. From the outset, in the work of “English” pioneers like F.D. Maurice and Charles Kingsley, the emphasis was on solidarity between the social classes, the cultivation of “larger sympathies,” the installation of national pride and the transmission of “moral” values.

Women followed workers as people for whom a literary education was deemed suitable, Eagleton notes:

English literature, reflected a Royal Commission witness in 1877, might be considered a suitable subject for “women…and the second- and third-rate men who…become schoolmasters.” The “softening” and “humanizing” effects of English, terms recurrently used by its early proponents, are within the existing ideological stereotypes of gender clearly feminine. The rise of English in England ran parallel to the gradual, grudging admission of women to the institutions of higher education; and since English was an untaxing sort of affair, concerned with the finer feelings rather than with the more virile topics of bona fide academic “disciplines,” it seemed a convenient sort of non-subject to palm off on the ladies, who were in any case excluded from science and the professions.

World War I changed all this. If before the war the English ruling class saw literature as a way to soften up striving women and rough working-class men, after the war sweetness and light seemed like a good idea for everyone, a way to make England whole again. Eagleton remarks that “it is a chastening thought that we owe the University study of English, in part at least, to a meaningless massacre.” Chief among literature’s advocates was Professor of English Literature at Oxford George Stuart Gordon, who in 1922 wrote,

England is sick, and … English literature must save it. The Churches (as I understand) having failed, and social remedies being slow, English literature has now a triple function: still, I suppose, to delight and instruct us, but also, and above all, to save our souls and heal the State.

The view of literature as salvation for a diseased West motivated the influential critic and scholar F. R. Leavis, whose focus on the literary canon and on close reading helped shape how literature is still studied today. In the 1920s, before Leavis, people saw literature as a pleasurable pastime. After Leavis, by the 1930s, they saw it as “the supremely civilizing pursuit, the spiritual essence of the social formation.”

As we have seen, Leavis was not the first literature enthusiast to make broad claims—remember Percy Shelley’s description of poets as “the unacknowledged legislators of the world”—but Eagleton will have none of it. Although passionately committed to literature, as a Marxist he believes that literature must be allied with political action for it to have real effect. Whatever one thinks of this stance, his response to Leavis is scathing:

Was it really true that literature could roll back the deadening effects of industrial labor and the philistinism of the media? It was doubtless comforting to feel that by reading Henry James one belonged to the moral vanguard of civilization itself; but what of all those people who did not read Henry James, who had never even heard of James, and would no doubt go to their graves complacently ignorant that he had been and gone? These people certainly composed the overwhelming social majority; were they morally callous, humanly banal and imaginatively bankrupt? One was speaking perhaps of one’s own parents and friends here, and so needed to be a little circumspect. Many of these people seemed morally serious and sensitive enough: they showed no particular tendency to go around murdering, looting and plundering, and even if they did it seemed implausible to attribute this to the fact that they had not read Henry James.

Leavisites, Eagleton declares, were “inescapably elitist,” betraying “a profound ignorance and distrust of the capacities of those not fortunate enough to have read English at Downing College.”

Eagleton then adds another twist. Just as there are people who don’t appear to have been harmed from not reading literature, there are others who have been harmed, or at least, not improved, from reading it:

For if not all of those who could not recognize an enjambement were nasty and brutish, not all of those who could were morally pure. Many people were indeed deep in high culture, but it would transpire a decade or so after the birth of [Leavis’s journal] Scrutiny that this had not prevented some of them from engaging in such activities as superintending the murder of Jews in central Europe. The strength of Leavisian criticism was that it was able to provide an answer…to the question, why read Literature? The answer, in a nutshell, was that it made you a better person. Few reasons could have been more persuasive than that. When the Allied troops moved into the concentration camps some years after the founding of Scrutiny, to arrest commandants who had wiled away their leisure hours with a volume of Goethe, it appeared that someone had some explaining to do.

Eagleton’s cautions are useful for those who expect literature to accomplish miracles. Skepticism is always called for when assessing literary impact. I find it necessary to push back here, however, just as Horace, Shelley, and Arnold push back against those who pooh-pooh literature. Sure, it’s always easy to cite instances where literature has proved ineffective, at least in the short run. One thinks of tyrants who encountered literature when young and still grew up to become tyrants. You haven’t proved much when you have said that, however.

Let’s look at Eagleton’s Goethe example since he uses it as a direct challenge to claims that literature makes us better people. We’ve cited previous theorists who, while lauding literature’s salutary effects, offer qualifications. Sir Philip Sidney, for instance, acknowledges that poetry—like physic, swords, and the Bible—can be used for ill as well as for good, depending on who is wielding it. It’s also true that some Nazis attempted to fashion Goethe into a pro-fascist writer. For instance, in at least one instance Faustus was depicted as “the archetypal German hero, whose efforts to win land from the sea in the final act of Faust, Part Two prefigured the Nazis’ own drive for more Lebensraum [historically destined expansion territory] in the East.”

That Nazis would fixate on Faust, as they did on Neitzsche’s Übermensch or Super Man, makes sense, and it’s true that Faust, like Hitler, claims as his higher purpose to reclaim new land for his emperor, dominating the sea in order to do so. When his ambitions are opposed by a rival emperor, Faustus unleashes Mephistopheles and three thugs to carry out the dirty work. Then having built himself a seaside castle, he becomes obsessed with a neighboring plot of land and orders Mephistopheles to seize that as well. What’s there for a fascist not to like?

The play then turns in a different direction, however. The land that Faust covets is owned by the kindly Baucis and Philemon, the quintessential good hosts from classical mythology who share the little they have with gods disguised as wandering beggars. Furthermore, Mephistopheles and his henchmen exceed Faust’s orders and kill the couple, along with a guest, in a mini-Holocaust of their own. Faust is so appalled at the consequences of his ambitions that he renounces his magical powers, gives over his imperial ambitions, and devotes himself to being of service to others. As a result, Faust, unlike Christopher Marlowe’s Faustus, gets his soul back, and the play ends with celebrations of nature and divine love. One can only wish that German fascists had followed suit.

If concentration commandants had employed Leavis’s close reading strategies, they could not have seen Goethe as a kindred soul. I’m of course joking when I say that. It could well be, however, that they were just reading selected excerpts of Goethe. Or, what I suspect is most likely, they didn’t so much engage with Goethe as genuflect before him, seeing him (as some Brits see Shakespeare) as a cultural marker or fetish of national greatness. They read him to signal their national superiority. I suspect German teachers were expected to teach very narrow versions of him in school.

Which returns us to the classroom. When Matthew Arnold, who had been a school inspector, looks to schools to emphasize class harmony and placate the masses, I suspect he wouldn’t want teachers teaching, say, Percy Shelley’s “Men of England” (“Men of England, wherefore plough/ For the lords who lay ye low?”) or William Blake’s “The Grey Monk” (“’I die, I die!’ the Mother said,/ ‘My children die for lack of bread.’”) He would want teachers teaching his favorite works with his intended message. When we explore Leavis’s claims that literature makes us better people, to some extent we must take into account who is teaching and what they consider as better.

I suggest we divide those teachers believing in literature’s life-changing powers into three categories, determined by political leaning: conservative Arnoldians, liberal Arnoldians, and radical Shelleyites. Conservative Arnoldians use literature to affirm traditional values, liberal Arnoldians use it to instill humanist values, and radical Shelleyites use it to fight for economic and social justice. All committed teachers may see it as their mission to use literature to produce good citizens and good people, but their criteria for “good” will vary.

Of course, there can be a gap between what teachers want students to learn and what students actually learn. If literature has the explosive power that Plato and others have attributed to it, then even the most careful attempts to circumscribe and manage it may not succeed. No matter how teachers deliver literature to their students, certain students will do with it what students do.