Monday

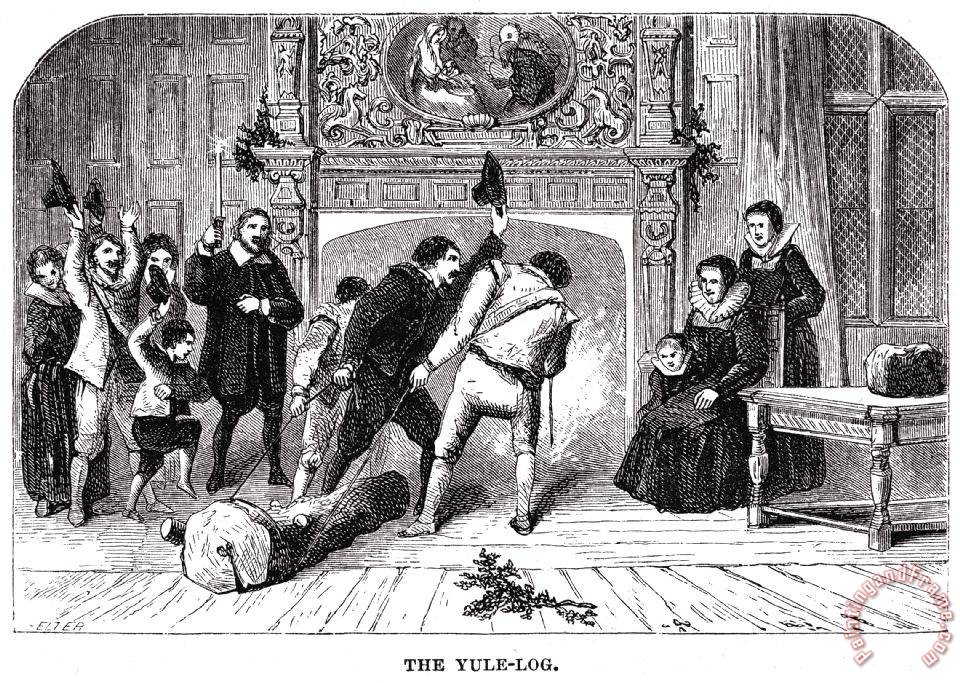

Yesterday I mentioned the syncretism involved in the nativity story, with images from a wide variety of traditions contributing to the manger scene. While the yule-log, which I write about today, is not connected with the manger, it was an integral part of many Christmas celebrations before central heating. The long-burning log affirms light in the season of darkness.

Incidentally, Jesus in all likelihood was not born on December 25. The date, fixed upon in the 3rd century, is probably based upon two seasonal moments of ancient significance. The Annunciation or conception of Jesus coincides roughly with the spring equinox, Christmas with the winter solstice. The promise of new life in the case of the first and light at the darkest time of year in the case of the second is so entrenched in Christian imagery that I doubt Christians would change course even if they suddenly discovered that Jesus was born in, say, May or October. The symbolism, I suspect, would prevail over historical fact.

Back to the symbolism of the yule-log. In “Yule-Tide” William Kean Seymour points out that the yule-log has roots in Mithras, an Indo-Iranian deity associated with light that was worshipped by Roman mystery cults; in the Greek fertility goddess Demeter, who celebrates the return of her kidnapped daughter Persephone each spring; in druidic fertility religions, which celebrate the same seasonal cycle; and in Roman Saturnalia, a time of merry making and gift giving dedicated to Saturn, a Roman god associated with “generation, dissolution, plenty, wealth, agriculture, periodic renewal and liberation” (Wikipedia). Saturn supposedly ruled during the lost Golden Age.

While the yule-log is mostly associated with northern Europe, I remember as a child reading a Harriet Tubman biography that described her as having the strength of a man and helping her fellow slaves drag in the annual yule-log. Apparently Maryland slaves didn’t have to work for as long as the yule-log burned, which meant that they selected the biggest log they could carry and then soaked it for days. Its connection with celebrating the birth of one who came “to proclaim freedom for the prisoners” and “to set the oppressed free” (Luke 4:18) is doubly appropriate. Light at a time of darkness indeed.

While religious fundamentalists complain about syncretistic elements and attempt to strip various symbols out of Christmas, for me the effect is to impoverish the occasion. The Christmas images carry weight precisely because they have been appropriated from older traditions. People attempting to touch the face of God borrow freely from what seems to work. They don’t care where it comes from.

Yule-Tide

Roman Saturnalia,

Christian Adoration,

Ivy wreath of Thalia,

Druid exaltation.

Spruce and fir and myrtle;

Mithras, God of Light;

How the yule-logs spurtle,

Blaze for Christmas Night!

Yule, or Jul (from Caesar:

Others claim Demeter--

Hymn they sang to please her,

Every graceful eater);

Giul or hiul (for wheeling

Winter orb of light):

Shadows wreathe the ceiling,

Dance on Christmas Night.

Ritual Germanic,

Gothic and Moravian,

Persian and Romanic,

Greek and Scandinavian.

Oel (or ale in plenty),

Yule-log blazing bright:

Dolce far niente,

Joy this Christmas Night.

Pagan Saturnalia,

Christian Adoration.

Christ—and Sun—the Savior,

Hear our Salutation!

An additional poem:

I don’t know whether Seymour’s poem influenced my father, but here’s his own syncretistic Christmas poem, written in response to various legal battles about Christian creches in public spaces. My analysis of the poem can be found here:

Christmas at the Courthouse

By Scott Bates

The wise-men are Egyptian,

The virgin birth, Antique;

The evergreen is Roman

The manger scene is Greek;

T’is the Saturnalian Season

When solar gifts are cool,

So Happy Birthday, Horus!

From our Multiculture School.