Tuesday

The other day I read an eye-popping Politico article (well, eye-popping for nerds like me) comparing Donald Trump to Antipope Benedict XIII, the last of the Avignon popes. Benedict lost his French support in 1398, escaped capture in 1403, and then held on and even regained some legitimacy before dying in 1423 (!). As I read the piece, I thought of how Dante handles Boniface VIII, the pope largely responsible for the Rome-Avignon schism a hundred years earlier.

If Antipope Benedict is like the Trump who has just left office, Dante’s Boniface is like the Trump who opened up a schism in the GOP, prompting many formerly loyal Republicans to dream of their own version of an alternative Avignon papacy.

Michael Kruse’s article opens as though it were about Trump, even though Benedict is the actual subject:

The ousted leader refused to relent to reality.

Set against a backdrop of avarice and inequality and persistent sickness, distrust and misrule, the leader exploited and exacerbated societal unrest to seize and flaunt vast power—doing anything and everything he could to try to keep it in his grip. He resisted pleas for unity and calm. He tested the loyalty of even his most ardent and important establishment supporters. He was censured and then toppled. Still, though, he declined to consider even the smallest acquiescence. Besieged and increasingly isolated, he faded as he aged—but he never yielded. Some people believed he had no less than the blessing of God.

The Trump parallels suggest foreboding possibilities for our own future:

He tried to exert control from a fortress of a palace in a separate seat of power—propped up by a stubborn type of papal court, retaining sufficient political capital to pressure heads of states to pick sides, bestowing benedictions and other benefits and if nothing else gumming up earnest efforts to allay divides. Weary, irritated leaders, both religious and royal, “said, ‘You’re out, you’re out, you’re out,’” [Medieval scholar Joëlle] Rollo-Koster told me, “and he said, ‘No, I’m in, I’m in, I’m in.’”

And then there’s this:

Manipulative and unabashed, he worked to cling to the trappings of power, sapped the sway of his counterpart popes and complicated attempts to mend the crippling split in the Roman Catholic Church called the Western Schism. Monarchs, clerics and other popes, his most potent adversaries, tried diplomacy, force and outright excommunication, ultimately stamping him a heretic—but they could never make the uncompromising Benedict altogether disappear. And there was an unexpected twist to Benedict’s intransigence, one Trump’s many high-ranking opponents would do well to heed: The harder and longer he held out, the more he was seen by some as a victim or a martyr, abidingly admired precisely because of his obstinacy and unwavering audacity.

Dante lambastes corrupt churchmen throughout the Divine Comedy, but Boniface VIII is his favorite target. Although Boniface was not yet dead in 1300 when the poem is set, he is mentioned by a number of souls in Inferno, Purgatory, and Paradise. For instance, the corrupt Pope Nicholas III, suffering hellish torments for using the papacy to build a fortune, initially thinks that Dante is Boniface and is confused. After all, he knows that Boniface won’t die until 1303, when he will be captured and beaten up by French forces:

“Are you there already, Boniface? Are you there

already?” he cried. “By several years the writ

has lied. And all that gold, and all that care –

are you already sated with the treasure

for which you dared to turn on the Sweet Lady

and trick and pluck and bleed her at your pleasure?

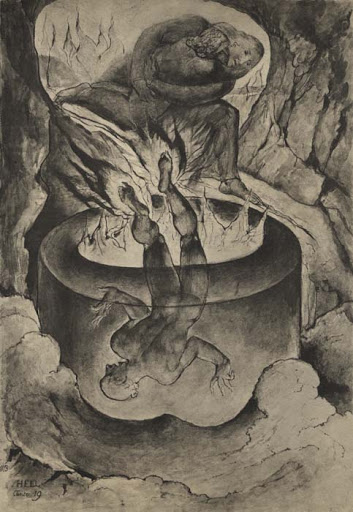

Nicholas has been inverted and stuck into a hole dug into rock, with only his legs protruding. His feet are on fire.

From every mouth a sinner’s legs stuck out

as far as the calf. The soles were all ablaze

and the joints of the legs quivered and writhed about.

Withes and tethers would have snapped in their throes.

As oiled things blaze upon the surface only,

so did they burn from the heels to the points of their toes.

“Master,” I said, “who is that one in the fire

who writhes and quivers more than all the others?

From him the ruddy flames seem to leap higher.”

To talk to the former pope, Dante must descend a level, where a hole in the side of the rock face allows conversation. He learns that, when Boniface dies, Nicholas will be pushed further into the hole as Boniface takes his place.

The punishment, as Gilbert and Sullivan’s Lord High Executioner puts it, fits the crime. As the latest in the apostolic succession that began with St. Peter (“the rock”), Nicholas and Boniface should be standing upright, their heads enveloped in a haloed glow. Instead, they have turned everything upside down. Dante compares the hole to a baptismal font, and the flaming feet are an inversion of the Pentecostal flames that marked the arrival of the Holy Spirit. In other words, when churchmen put money before God, they receive a grotesque parody of divine grace.

Dante is so infuriated by such corruption that he excoriates Nicholas (and by extension Boniface) in the way many of us would like to excoriate Trump for violating his oath of office and sacrificing America to his greed and ego:

Maybe — I cannot say — I grew too brash

at this point, for when he had finished speaking

I said: “Indeed! Now tell me how much cash

our Lord required of Peter in guarantee

before he put the keys into his keeping?

Surely he asked nothing but ‘Follow me!’

Nor did Peter, nor the others, ask silver or gold

of Matthias when they chose him for the place

the despicable and damned apostle sold.

Therefore stay as you are; this hole well fits you —

and keep a good guard on the ill-won wealth…

And were it not that I am still constrained

by the reverence I owe to the Great Keys

you held in life, I should not have refrained

from using other words and sharper still;

for this avarice of yours grieves all the world,

tramples the virtuous, and exalts the evil.”

Dante goes on to compare Nicholas to the Whore of Babylon (in the Book of Revelation) before concluding,

Gold and silver are the gods you adore!

In what are you different from the idolator,

save that he worships one, and you a score?

There’s no question about what Trump adores. Unfortunately, like Antipope Benedict, he still commands enough allegiance from Trump idolaters to cause problems for the country he once swore to honor and protect.

Addendum: Sewanee English professor Ross MacDonald, a member of our Dante Discussion Group, pointed out that Nicholas’s inversion is also a grotesque parody of St. Peters’s crucifixion. So as not to imitate Jesus, Peter asked to be crucified upside down. Again, the contrast between Peter and his successors could not be more stark.