Over Thanksgiving I read the remarkable and widely applauded Fun House (2006), an illustrated memoir by Alison Bechdel, author of the syndicated comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. Bechdel drew me in by how she turned to literary works to deal with the contradictions in her upbringing.

The Bechdels lived in a small town in New York. Bechdel focuses especially on her problematic relationship with her father, who was an English teacher, funeral home director, and closeted gay man. She believes he deliberately allowed himself to be hit by a truck while she was away at college, perhaps because he had been getting in trouble with the law for soliciting students, shoplifting, and other crimes.

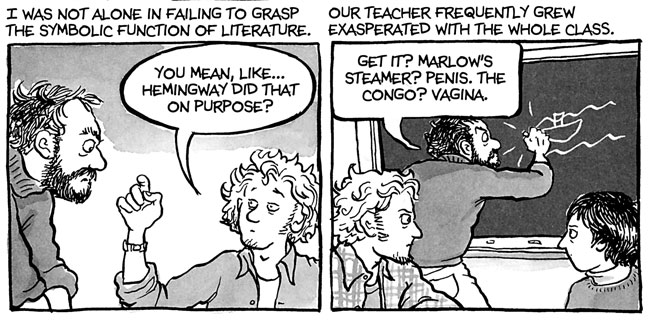

The Bechdels were never sure what to expect from their father from one moment to the next. As Bechdel puts it, “His bursts of kindness were as incandescent as his tantrums were dark.” In one extended analogy early in the book, she describes him as Daedalus as he obsessively restores an old Victorian house. The resulting “labyrinth” captures their tangled family life. To do justice to the text, you need to see it along with the pictures, but this will give you a taste:

He would perform, as Daedalus did, dazzling displays of artfulness…Daedalus, too, was indifferent to the human cost of his projects. He blithely betrayed the king, for example, when the queen asked him to build her a cow disguise so she could seduce the white bull. Indeed, the result of that scheme—a half-bull, half-man-monster—inspired Daedalus’s greatest creation yet. He hid the minotaur in the labyrinth—a maze of passages and rooms opening endlessly into one another and from which, as stray youths and maidens discovered to their peril, escape was impossible.

The half-bull, half-man monster is a powerful description of Bechdel’s closeted father and reminds me of Lucille Clifton comparing her abusive father to Wolf Man. As Bechdel sees it, her father built the house in such a way as to contain himself:

The embarrassment on my part was a tiny scale model of my father’s more fully developed self-loathing. His shame inhabited our house as pervasively and invisibly as the aromatic musk of aging mahogany. In fact, the meticulous period interiors were expressly designed to conceal it. Mirrors, distracting bronzes, multiple doorways. Visitors often got lost upstairs.

My mother, my brothers, and I knew our way around well enough, but it was impossible to tell if the minotaur lay beyond the next corner.

At one point Bechdel explains why she so often turns to literature to describe her parents:

I employ these allusions to James and Fitzgerald not only as descriptive devices, but because my parents are most real to me in fictional terms. And perhaps my cool aesthetic distance itself does more to convey the arctic climate of our family than any particular literary comparison.

Among the classics mentioned by the memoir are:

The Great Gatsby

After [reading Fitzgerald’s] biography, [my father] tore through Fitzgerald’s stories, seeing himself in various characters… Dad does not mention identifying Gatsby’s self-willed metamorphosis from farm boy to prince is in many ways identical to my father’s.

Like Gatsby, my father fueled this transformation with “the colossal vitality of his illusion.” Unlike Gatsby, he did it on a school teacher’s salary.

Washington Square

If my father was a Fitzgerald character, my mother stepped right out of Henry James—a vigorous American idealist ensnared by degenerate continental forces. A plain, dull, but wealthy young woman falls in love with the smooth-talking fortune hunter, Morris Townsend.

Taming of the Shrew

My parents met, I eventually extracted from my mother, in a performance of The Taming of the Shrew…It’s a troubling play, of course. The willful Katherine’s spirit is broken by the mercenary, domineering Petrucchio…Even in those pre-feminist days, my parents must have found this relationship model to be problematic. They would probably have been appalled at the suggestion that their own marriage would play out in a similar way.

Portrait of a Lady

If The Taming of the Shrew was a harbinger of my parents’ later marriage, Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady runs more than a little parallel to their early years together. Isabel Archer, the heroine, leaves America for Europe. She’s filled with heady notions about living her life free from provincial convention and constraint.

Isabel turns down a number of worthy suitors, but perversely accepts Gilbert Osmond, a cultured, dissipated, and penniless European art collector. My parents made a trip to Paris soon after their wedding, to visit an army friend of my father’s. They had a terrible fight in the car. Later, my mother would learn that dad and his friend had been lovers. Much like Isabel Archer learns that Gilbert had been having an affair all along with the woman who introduced them.

But too good for her own good, Isabel remains with Gilbert. And despite all her youthful hopes to the contrary, ends up “ground in the very mill of the conventional.”

Wallace Stevens, Sunday Morning

[Quoted in the memoir as her mother’s favorite poem]

Complacencies of the peignoir, and late

Coffee and oranges in a sunny chair,

And the green freedom of a cockatoo

Upon a rug mingle to dissipate

The holy hush of ancient sacrifice.

She dreams a little, and she feels the dark

Encroachment of that old catastrophe,

As a calm darkens among water-lights.

It’s about the crucifixion. In many ways my mother’s Catholicism was more form than content, but sacrifice was a principle that she grasped instinctively. Perhaps she also liked the poem because its juxtaposition of catastrophe with a plush domestic interior is life with my father in a nutshell. Dad’s death was not a new catastrophe but an old one that had been unfolding very slowly for a long time.

Gatsy and Fitzgerald again

The idea that I caused his death by telling my parents I was a lesbian is perhaps illogical. Causality implies connection, contact of some kind, and however convincing they might be, you can’t lay hands on a fictional character.

There’s a scene in The Great Gatsby where a drunken party guest is carried away by the discovery that the volumes in Gatsby’s library are not cardboard fakes. “What thoroughness, what realism!” he exclaims. “Knew when to stop, too. Didn’t cut the pages!”

My father’s books—the hardbound ones with their ragged dust jackets, the paperbacks with their creased spines—had clearly been read. But in a way Gatsby’s pristine books and my father’s worn ones signify the same thing—the preference of a fiction to reality. If Fitzgerald’s own life hadn’t turned from fairy tale to tragedy, would his stories of disenchantment have resonated so deeply with my father? Gatsby in the pool, Zelda in the asylum, Scott in Hollywood, an alcoholic dying of a heart attack at forty-four.

My father was forty-four when he died, too. Struck by the coincidence, I counted out their lifespans. The same number of months, the same number of weeks—but Fitzgerald lived three days longer.

For a wild moment I entertained the idea that my father had timed his death with this in mind, as some sort of deranged tribute.

But that would only confirm that his death was not my fault. That, in fact, it had nothing to do with me at all. And I’m reluctant to let go of that last, tenuous bond.

I’ll report on the second half of the book in a later post. But better yet, go out and buy a copy for yourself.

2 Trackbacks

[…] « Bechdel Uses Lit to Understand Her Life […]

[…] Bechdel Uses Lit to Understand Her Life […]