Spiritual Sunday

As we are in the Lenten season, the liturgy has of reading one of the strangest passages in the Bible, that being Ezekiel’s vision of dry bones. I repost today an essay from April 6, 2016 on T. S. Eliot’s allusion to the imagery. Given how desolate many of us are feeling these days, it’s worth revisiting both the Biblical passage and Eliot’s poem.

Reposted from April 6, 2016

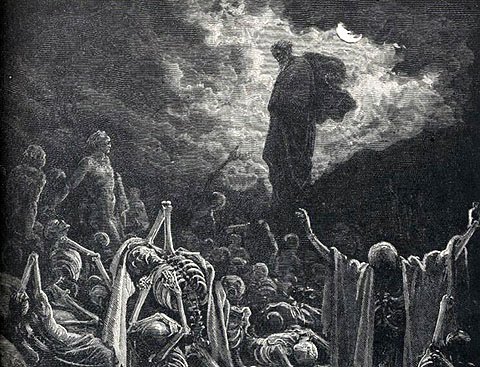

I find one of the strangest passages in the Bible to be Ezekiel’s valley of dry bones, which we will hear in church today. Although Ezekiel envisions a happy ending for his bones, the image of death and sterility is so grim and unsettling that T. S. Eliot uses it as one of his foundational images in The Waste Land (1922). Yet for all his pessimism, Eliot’s hints at a possibility of spiritual renewal.

Here’s the passage from Ezekiel (37:1-14):

The hand of the Lord came upon me, and he brought me out by the spirit of the Lord and set me down in the middle of a valley; it was full of bones. He led me all around them; there were very many lying in the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, “Mortal, can these bones live?” I answered, “O Lord GOD, you know.” Then he said to me, “Prophesy to these bones, and say to them: O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord. Thus says the Lord GOD to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live. I will lay sinews on you, and will cause flesh to come upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and you shall live; and you shall know that I am the Lord.”

So I prophesied as I had been commanded; and as I prophesied, suddenly there was a noise, a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to its bone. I looked, and there were sinews on them, and flesh had come upon them, and skin had covered them; but there was no breath in them. Then he said to me, “Prophesy to the breath, prophesy, mortal, and say to the breath: Thus says the Lord GOD: Come from the four winds, O breath, and breathe upon these slain, that they may live.” I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood on their feet, a vast multitude.

Then he said to me, “Mortal, these bones are the whole house of Israel. They say, `Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are cut off completely.’ Therefore prophesy, and say to them, Thus says the Lord GOD: I am going to open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. And you shall know that I am the Lord, when I open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people. I will put my spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you on your own soil; then you shall know that I, the Lord, have spoken and will act,” says the Lord.

My friend John Morrow, a retired Episcopal priest, says that the story reflects God’s deep and abiding love for his people. If He can create Adam out of dust, He can breathe new life into those who have lost touch with Him.

Eliot is describing a world where people feel cut off from spiritual meaning. His first reference to the bones occurs as part of a sterile domestic conversation in Part II (“The Game of Chess”), a scene that may be based on Eliot’s own troubled relationship with his first wife. Hearing her incessant complaining, he silently thinks of Ezekiel’s valley:

“My nerves are bad tonight.

Yes, bad. Stay with me.

“Speak to me. Why do you never speak. Speak.

“What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

“I never know what you are thinking. Think.”

I think we are in rats’ alley

Where the dead men lost their bones.

The poem continues on with an ironic allusion to the divine breath that God promises the people of Israel. In this case, the wind is empty:

“What is that noise?”

The wind under the door.

“What is that noise now? What is the wind doing?”

Nothing again nothing.

Bones show up twice in Part III (“The Fire Sermon”), the first time in a terrifying echo of a line from Andrew Marvell’s famous carpe diem poem “To His Coy Mistress.” Pleading for his mistress to yield to his overtures, Marvell’s speaker comes up with a startling version of “gather ye rosebuds while ye may”:

But always at my back I hear

Time’s winged chariot hurrying near.

Eliot drops Marvell’s cavalier tone and describes only our grim condition:

But at my back in a cold blast

I hear

The rattle of the bones, and chuckle spread from ear to ear.

The poet then returns to the image of the impotent fisher king that is at the core of the poem. At the same time, rats make a repeat appearance, prompting us to wonder about the state of Eliot’s London apartment. The passage also has images of death (Ferdinand in The Tempest mourning his father’s apparent death) and of sterile sexuality (“white bodies naked”):

A rat crept softly through the

vegetation

Dragging its slimy belly on the bank

While I was fishing in the dull canal

On a winter evening round behind the gashouse

Musing upon the king my brother’s wreck

And on the king my father’s death before him.

White bodies naked on the low damp ground

And bones cast in a little low dry garret,

Rattled by the rat’s foot only, year to year.

In Part IV (“Death by Water”), there is another image of bones being picked clean, although this time they are not dry bones. Nevertheless, the image has the same effect:

Phlebas the Phoenician, a

fortnight dead,

Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep sea swell

And the profit and loss.

A current under sea

Picked his bones in whispers.

Finally, in Part V (“What the Thunder Said”), we have yet more images of death with no resurrection: a decayed hole (Jesus’s tomb?), overgrown graves, an empty chapel, and a door swinging helplessly in the wind. These dry bones will “harm no one”:

In this decayed hole among the

mountains

In the faint moonlight, the grass is singing

Over the tumbled graves, about the chapel

There is the empty chapel, only the wind’s home.

It has no windows, and the door swings,

Dry bones can harm no one.

Despite the grim images, however, there is subsequently a hint that resurrection may be on its way, although Eliot detects no more than a hint. A cock crows—think of Henry Vaughan’s poem about the resurrected Jesus as a rooster—and then there is a flash of lightning and “a damp gust/bringing rain.” This is not “the dry sterile thunder without rain” from earlier in the poem. There may be hope after all.

Eliot does not offer us easy grace in this poem. He does not have Ezekiel’s energizing faith as he struggles with deep spiritual depression. But because his hints of spiritual redemption are so hard won, they have a ring of truth to them.