Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Monday

I’ve been looking for a literary analogue for our Supreme Court and have decided the rightwing members are a lot like Vernon and Petunia Dursley from the Harry Potter books: they spoil their son Dudley (Donald Trump) while forcing their orphaned nephew Harry (Trump’s opponents) to sleep in the closet underneath the stairwell.

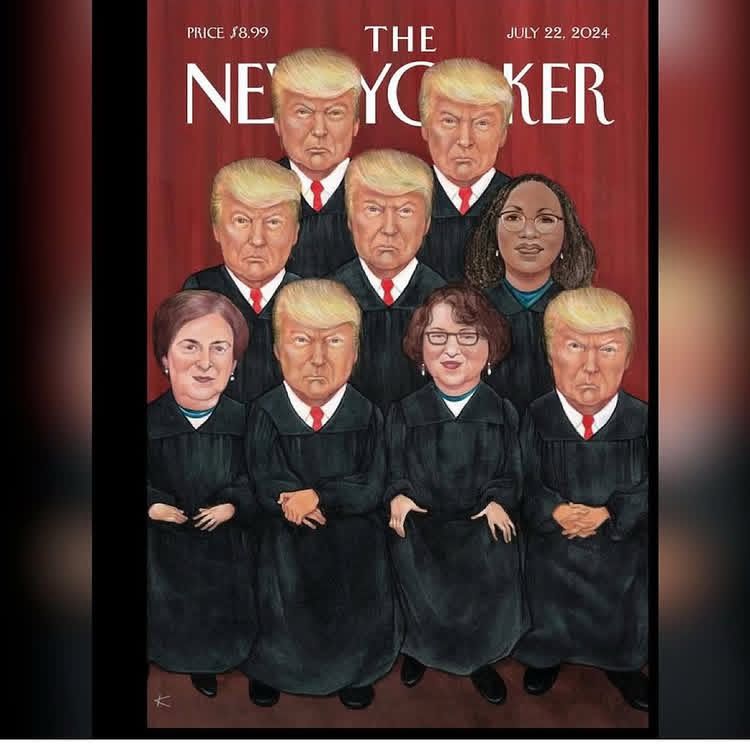

The spoiling came most recently in their decision to prevent lower courts from issuing national injunctions against Trump’s desire to strip the children of immigrants of their birthright citizenship. Never mind that SCOTUS had no problems with lower courts issuing national injunctions against various of Biden’s policies, especially regarding student loans and Covid regulations. It’s only an issue when courts block Trump measures.

To overrule the lower courts in this case is particularly alarming since gaining citizenship upon being born here is one of our most fundamental rights, guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. The Trump administration can now go ahead and start stripping individuals of citizenship here or there with no court other than SCOTUS able to stop him. And who knows how they’ll rule? As Ruth Marcus notes in the New Yorker,

Friday’s decision means that courts are now hobbled from stopping any of the Administration’s actions, no matter how unconstitutional they may be, nor how much damage they will inflict. Once again, the Court’s conservative super-majority abandoned its constitutionally assigned role and dangerously empowered the President. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor put it in her dissent, “its decision is nothing less than an open invitation for the Government to bypass the Constitution.”

And of course, this is the only most recent instance of SCOTUS favoring Trump. Recently, it has allowed people to be sent to foreign prisons without any right to contest their deportations. And last year it decided to grant Trump immunity for all “presidential acts,” which apparently include instigating a coup attempt. Increasingly, Trump sees himself as having been giving blanket permission to break any law he chooses, and he has proven himself more than willing to do so.

To be sure, SCOTUS was already trending towards to the extreme right even before Trump, especially with its Citizens United decision, which allowed corporate and foreign money to flood the political system. But with Trump in the Oval Office, the trend has accelerated.

Think of SCOTUS’s gifts to Trump as the presents than Dudley receives on his eleventh birthday:

The table was almost hidden beneath all Dudley’s birthday presents. It looked as though Dudley had gotten the new computer he wanted, not to mention the second television and the racing bike. Exactly why Dudley wanted a racing bike was a mystery to Harry as Dudley was very fat and hated exercise—unless of course it involved punching somebody. Dudley’s favorite punching bag was Harry…

Once one starts comparing Dudley to Trump, the resemblances don’t stop. For instance, there’s Dudley’s physique and his hair:

He had a large pink face, not much neck, small, watery blue eyes, and thick blond hair that lay smoothly on his thick, fat head. Aunt Petunia often said that Dudley looked like a baby angel—Harry often said that Dudley looked like a pig in a wig.

Dudley even has the same insatiable appetite that Trump does:

Dudley, meanwhile, was counting his presents. His face fell. “Thirty-six,” he said, looking up at his mother and father. “That’s two less than last year.”

The three liberal justices, along with most lawyers and judges, are keenly aware of how Trump games the system. The rightwing justices, however, blithely ignore his legal shenanigans, doing a version of the Vernon-Petunia dance. After pointing out that Dudley missed one present, Petunia then promises him more goodies:

Aunt Petunia obviously scented danger, too, because she said quickly, “And we’ll buy you another two presents while we’re out today. How’s that, popkin? Two more presents. Is that all right?”

Dudley thought for a moment. It looked like hard work. Finally he said slowly, “So I’ll have thirty…thirty…”

“Thirty-nine, sweetums, said Aunt Petunia.

“Oh.” Dudley sat down heavily and grabbed the nearest parcel. “All right then.”

Uncle Vernon chuckled.

“Little tyke wants his money’s worth, just like his father. “Atta boy, Dudley!” He ruffled Dudley’s hair.

Think of Justice John Roberts essentially ruffling Trump’s hair.

One doesn’t need to be a child psychologist to know how bad this is for a child. Nor does it take an expert on authoritarianism to know that attempting to placate a tyrant never ends well. After receiving 37 presents, Dudley is upset that Harry will be allowed to join them on his birthday outing. His display of self-pity bears no small resemblance to Trump’s incessant complaints that “nobody’s been treated badly like me”:

Dudley began to cry loudly. In fact, he wasn’t really crying—it had been years since he’s really cried—but he knew that if he screwed up his face and wailed, his mother would give him anything he wanted.

“Dinky duddydums, don’t cry. Mummy won’t let him spoil your special day!” she cried, flinging her arms around him.

“I…don’t…want…him…t-t-to come!” Dudley yelled between huge, pretend sobs. “He always sp-spoils everything!” He shot Harry a nasty grin through the gap in his mother’s arms.

Thanks to such parenting, Dudley follows a Trump-like arc, at first becoming immensely fat and then, when he starts boxing, using his new-found strength to become an even bigger bully. The only difference from Trump is that Dudley does undergo a conversion of sorts, becoming softer and more friendly after Harry saves him from the Dementors.

The Dursley parents, however, never apologize for what they have done, nor does it appear that SCOTUS’s rightwing members will do so. John Roberts, even as he decries increasing attacks on the judiciary, does not acknowledge the role the 6-3 majority has played in delegitimizing the court. They were tasked with a sacred mission, to uphold the rule of law, and have been bending the law to suit their own political biases. One wishes that there was someone in a position of authority who could lecture them as Albus Dumbledore lectures Vernon and Petunia.

Telling them that their sacred duty was to care for Harry “as though he were your own,” Dumbledore continues,

You did not do as I asked. You have never treated Harry as a son. He has known nothing but neglect and often cruelty at your hands. The best that can be said is that he has at least escaped the appalling damage you have inflicted upon the unfortunate boy [Dudley] sitting between you.

The damage SCOTUS has inflicted upon Trump is removing all guardrails to his behavior. And because he will appear to cry bitterly every time he is thwarted, it appears that they will not be changing their behavior anytime soon.