Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

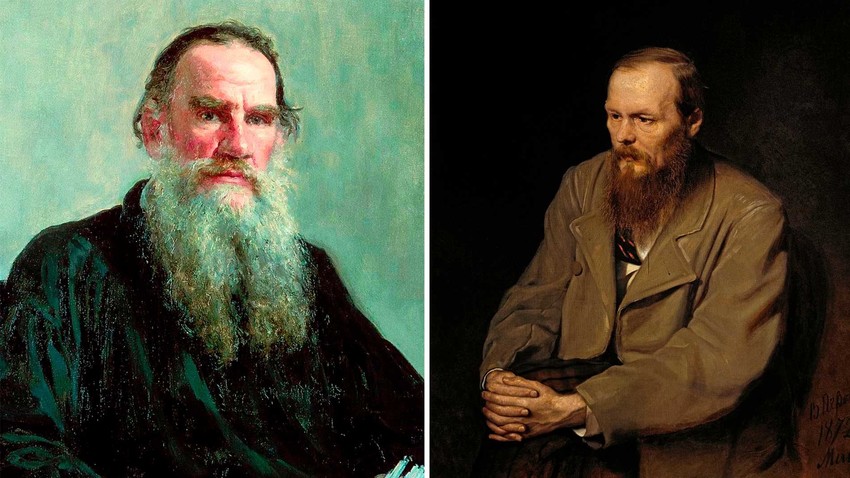

A couple of months ago I came across an illuminating article wondering how Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky would respond to the Ukraine invasion. Although Dostoevsky became a believer in Russian exceptionalism, University of Kansas Russian professor Ani Kokobobo is fairly sure he, along with Tolstoy, would be appalled at Russia’s behavior. She writes,

Seeing the rubble of a theater in Mariupol, hearing of Mariupol citizens starving because of Russian airstrikes, I wonder what Dostoevsky – who specifically focused his piercing moral eye on the question of the suffering of children in his 1880 novel The Brothers Karamazov – would say in response to the Russian army’s bombing a theater where children were sheltering. The word “children” was spelled out on the pavement outside the theater in large type so it could be seen from the sky. There was no misunderstanding of who was there.

Ivan Karamazov explores acts of barbarity targeting children in the “Rebellion” chapter. Confronted with unmerited suffering, he challenges the Christian vision of divine harmony. Because, as he sees it, belief in a divine plan prompts us to pass over horrors, he declares, “I don’t want harmony. From love for humanity I don’t want it. I would rather be left with the unavenged suffering.”

Ivan’s account of child torture gives us some insight into Russian war crimes. After describing Turkish soldiers cutting fetuses out of women’s bellies and catching babies on their bayonets, he moves on to Russian atrocities. At one point he tells a story about abusive parents:

This poor child of five was subjected to every possible torture by those cultivated parents. They beat her, thrashed her, kicked her for no reason till her body was one bruise. Then, they went to greater refinements of cruelty—shut her up all night in the cold and frost in a privy, and because she didn’t ask to be taken up at night (as though a child of five sleeping its angelic, sound sleep could be trained to wake and ask), they smeared her face and filled her mouth with excrement, and it was her mother, her mother did this. And that mother could sleep, hearing the poor child’s groans!

Ivan accompanies his report with a psychological analysis of sadism:

It’s just their defenselessness that tempts the tormentor, just the angelic confidence of the child who has no refuge and no appeal, that sets his vile blood on fire. In every man, of course, a demon lies hidden—the demon of rage, the demon of lustful heat at the screams of the tortured victim, the demon of lawlessness let off the chain…

In her article Kokobobo also mentions Crime and Punishment, pointing out how Doestoevsky explains the toll of murder on the murderer—how, “when someone takes a life, they kill part of themselves.” How can someone who has read such a book, she wonders, “possibly accept Putin’s vision of Russia?” She feels sure that Dostoevsky, “Russia’s greatest metaphysical rebel,” would have “recoiled and rebelled against Russian violence in Ukraine.”

She says the same about Tolstoy, noting that, in his last work (Hadji Murat), he scrutinizes Russia’s colonial exploits in North Caucasus. There he shows “how senseless Russian violence toward a Chechen village caused instant hatred of Russians.”

In War and Peace, meanwhile,

Tolstoy contends that the morale of the Russian military is the key to victory. The battles most likely to succeed are defensive ones, in which soldiers understand why they are fighting and what they are fighting to protect: their home.

The novel has episodes which are only too applicable to current Russian and Ukrainian families who have lost members. There of vivid descriptions of

young Russian soldiers coming into direct confrontation with the instruments of death and destruction on the battlefield. They disappear into the crowd of their battalion, but even a single loss is devastating for the families awaiting their safe return.

And then there’s Anna Karenina. Kokobobo explains that the last part originally wasn’t published

because it criticized Russia’s actions in the Russo-Turkish war. Tolstoy’s alter ego in that novel, Konstantin Levin, calls the Russian intervention in the war “murder” and thinks it is inappropriate that Russian people are dragged into it.

“The people sacrifice and are always prepared to sacrifice themselves for their soul, not for murder,” he says.

And then there’s Tolstoy’s passage from his 1900 essay “Thou Shalt Not Kill.” It captures only too well Russia’s current situation:

The misery of nations is caused not by particular persons, but by the particular order of Society under which the people are so bound up together that they find themselves all in the power of a few men, or more often in the power of one single man: a man so perverted by his unnatural position as arbiter of the fate and lives of millions, that he is always in an unhealthy state, and always suffers more or less from a mania of self-aggrandizement.

One thinks of the close to million Russians that have fled their country since the invasion began when one hears about how Tolstoy helped a Russian Christian sect (the Doukhobors) Tolstoy avoid conscription. The proceeds from his 1899 novel Resurrection, a powerful exploration of prison life, went to help them emigrate to Canada rather than fight in the Russian army.

Kokobobo notes that the imprisoned opposition figure Alexei Navalny, whom Putin has imprisoned, quoted Tolstoy in a twitter message to his followers:

Act clearly, as Leo Tolstoy, one of our great writers, whose quote I ended my speech with, bequeathed: “War is a product of despotism. Those who want to fight war must only fight despotism.”

The article concludes by quoting Ukrainian artist Alevtina Kakhidze, who, addressing Russian supporters of the invasion, wrote, “I’ve read your f—ing literature. But looks like Putin did not, and you have forgotten.”

Even the greatest literature, sadly, cannot prevent atrocities. Nevertheless, it provides a moral compass that societies can turn to when the going gets rough.