Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Wednesday

A Washington Post review of Somehow, Anne Lamott’s latest book, notes that she concludes with a William Blake passage. This gives me an excuse to write about “The Little Black Boy,” which is brilliant in its handling of race. I also take this occasion to express my appreciation for Lamott.

Like many writing teachers, I have used her Bird by Bird in the classroom, especially Lamott’s advocacy of the “shitty first draft.” One of the major hurdles faced by writers is breaking the silence of the blank page or blank screen. If beginning writers come to think differently about their halting first efforts, the process becomes a lot easier.

I’m also a fan of Lamott’s observation that “you can safely assume you’ve created God in your own image when it turns out God hates all the same people you do.” While this may put us in mind of various resentment-crazed fundamentalists, Lamott does not exempt herself. “My lifelong cross to bear,” she writes in Somehow, “has been secret derisive judgment, a pinball machine of sizing up everything and everyone.” To which she adds, “I am working on it, but the healing is going slightly more slowly than one would hope.”

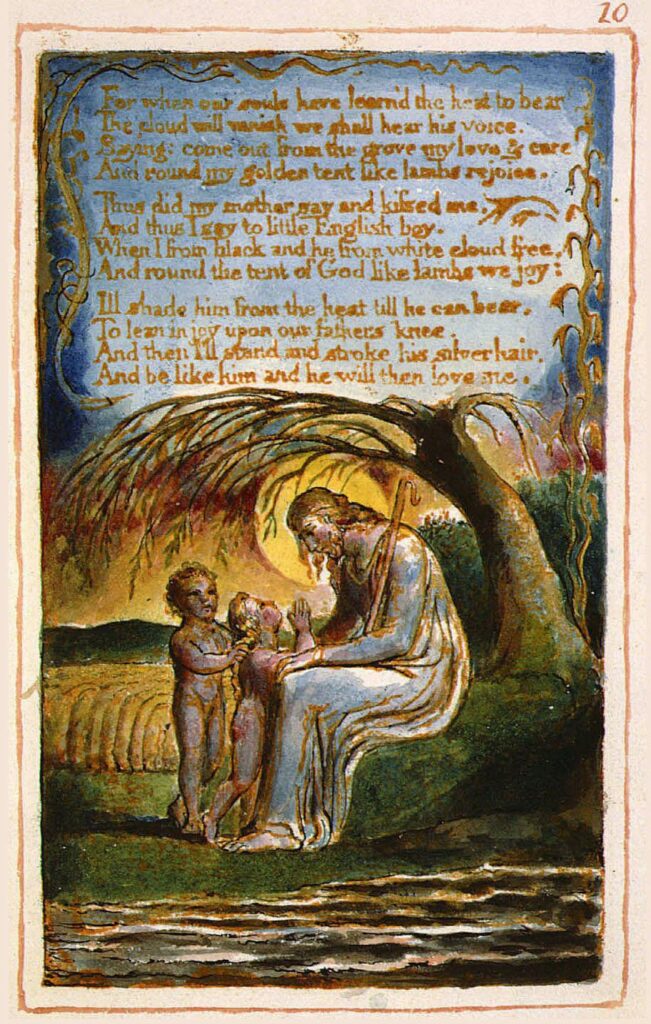

According to the review, Lamott’s latest book ends with the Blake passage, “And we are put on earth a little space, that we may learn to bear the beams of love.” The reviewer observes, “No matter one’s external descriptors, Lamott speaks to the human in all of us, challenging us to bear her beam of love, and our own.”

The poem in which the line appears is more complex than it first seems:

The Little Black Boy

By William Blake

My mother bore me in the southern wild,

And I am black, but O! my soul is white;

White as an angel is the English child:

But I am black as if bereav’d of light

My mother taught me underneath a tree

And sitting down before the heat of day,

She took me on her lap and kissed me,

And pointing to the east began to say.

Look on the rising sun: there God does live

And gives his light, and gives his heat away.

And flowers and trees and beasts and men receive

Comfort in morning joy in the noonday.

And we are put on earth a little space,

That we may learn to bear the beams of love,

And these black bodies and this sun-burnt face

Is but a cloud, and like a shady grove.

For when our souls have learn’d the heat to bear

The cloud will vanish we shall hear his voice.

Saying: come out from the grove my love & care,

And round my golden tent like lambs rejoice.

Thus did my mother say and kissed me,

And thus I say to little English boy.

When I from black and he from white cloud free,

And round the tent of God like lambs we joy:

Ill shade him from the heat till he can bear,

To lean in joy upon our fathers knee.

And then I’ll stand and stroke his silver hair

And be like him and he will then love me.

What first stands out is the color imagery, with whiteness being associated with goodness and purity and black the opposite. But rather than endorse this view, Blake is instead pointing out that the little Black boy has internalized the racial hierarchy. He thinks the little English boy will see him as white—and come to love him—only if he is loving and shields him from the heat.

We know from our racial history—and so did Blake—that such submissive behavior will only feed the White boy’s sense of entitlement and privilege. In fact, this is how slaveholders wanted their slaves to behave, remaining docile as the sun burned their faces in the cotton, rice, and cane fields. Blake is a master of irony who doesn’t hesitate to contrast the innocence of children with the hypocrisy of their Christianity-professing elders.

In “Holy Thursday,” for instance, he contrasts the orphans who are being marched to church—who raise a “mighty wind” as they pour out their hearts in hymn singing—with the “grey-headed beadles” who use their staffs to corral them. (Blake ironically compares these staffs to “wands as white as snow.”) Once you are attuned to Blake’s irony, you can almost hear him spit out, as sanctimonious pabulum, the final lines: “Beneath them sit the aged men wise guardians of the poor/ Then cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door.”

Can you detect the sarcasm? These “wise guardians of the poor” have long ago driven angels from their doors.

They’ve also benefited from the racial hierarchy in “Little Black Boy,” using Christianity to buttress their positions of power. Central to Blake’s vision is Jesus’s admonition to his ambitious disciples in Matthew 18:3-5:

I tell you the truth, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Therefore, whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. And whoever welcomes a little child like this in my name welcomes me.

And lest you miss the point in his first “Holy Thursday” poem (found in Songs of Innocence), Blake has a companion “Holy Thursday” poem in Songs of Experience. Here he doesn’t couch his point in irony:

Is this a holy thing to see,

In a rich and fruitful land,

Babes reducd to misery,

Fed with cold and usurous hand?

Is that trembling cry a song?

Can it be a song of joy?

And so many children poor?

It is a land of poverty!

And their sun does never shine.

And their fields are bleak & bare.

And their ways are fill’d with thorns.

It is eternal winter there.

In our own rich and fruitful land, meanwhile, we have self-professed Christian legislators rolling back child labor laws and cutting support systems for poor families while voting in large tax breaks for the wealthiest Americans. Often in the name of Christ.

What is miraculous is that love manages to make itself heard at all. Lamott turns to Blake, and to his little Black boy, to make sure the message gets through.