Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and I will send it/them to you. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Tuesday

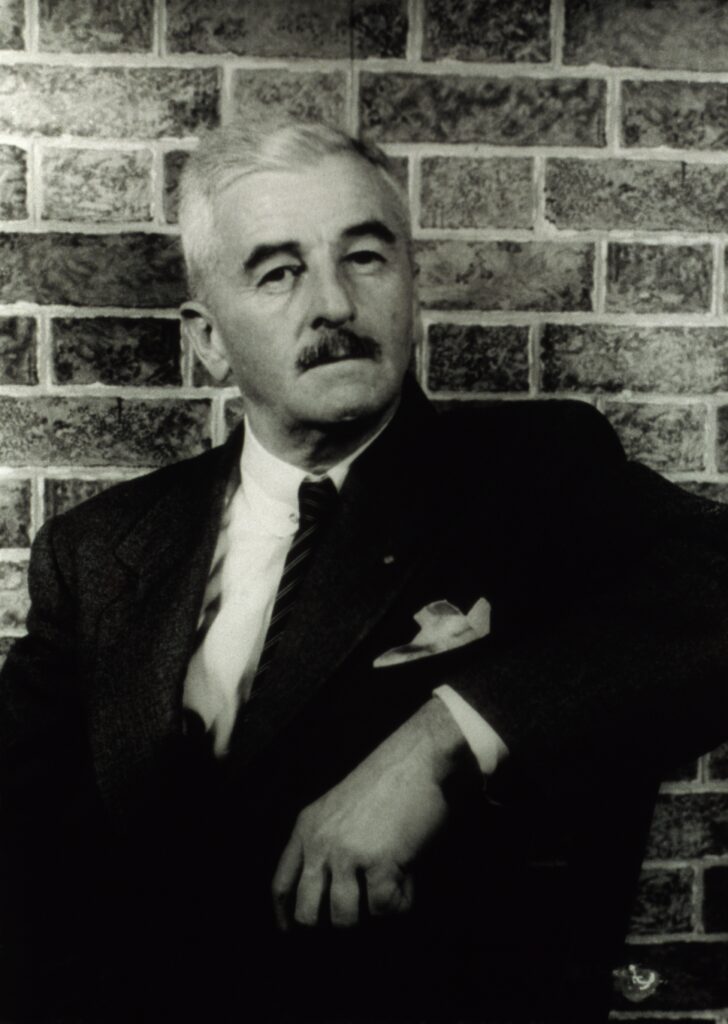

Last week, when writing about William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, I mentioned feeling pounded by the n-word. I found the work brilliant nevertheless, a brilliant expose of how White America’s obsession with race is both nonsensical and deeply corrupting. Since I think it vital that American students become familiar with such a vision, I share today some thoughts about how teachers can handle works that make prominent use of the epithet. After all, the first impulse of many upon encountering it is to reject the work altogether, thereby missing out on the important wisdom to be gained.

Let me start with my own history with the word. I was born in 1951 and my family moved to Sewanee, Tennessee in 1954, when I was three. My first awareness that something was wrong occurred when I was eight and was chanting to someone younger than I (John Mayfield) a rhyme I had picked up in school:

Teacher, teacher, don’t hit me,

Hit that [n-word] behind that tree.

John started complaining vociferously but that just meant that I, amazed that my words had special power, kept repeating it to plague him. Finally he told his parents, which led to a discussion. While I wasn’t chastised, I learned something was amiss and we arrived at a compromise, replacing the n-word with “tiger.”

Being a dutiful child, I stopped using the n-word from that day forward, but I continued to hear it constantly from my peers. I remember someone, for instance, referring to the Black section of Sewanee as [n-word]town. When we had our first Black student at Sewanee Public School, I remember one of my classmates calling him the n-word to his face and of him deflating the bully with a smile, a response (as I learned years later) his mother had coached all her children to use.

While Sewanee faculty—the adults I saw most often—were liberals who considered the n-word abhorrent, I would hear it from adults down in the valley. Or rather, I would hear “nigra,” which was a compromise between “Negro”—which granted too much respect—and the n-word, which by then was being associated with the people referred to as “white trash” (itself an objectionable slur).

Because of the racism, I fled as far from the south as I could for college, attending Carleton in Northfield, Minnesota. While I encountered racism in rural Minnesota as well, it wasn’t as blatant. Therefore, returning to Sewanee for the year before graduate school felt like a return to my childhood. Working for the Winchester Herald-Chronicle, I heard the n-word daily, especially from the paper’s publisher.

Rather than building up an immunity to the word, I experienced the opposite, feeling increasingly ill each time I encountered it. A rightwing Slovenian professor once tried the word out on me just to gauge its effect and got what he was looking for as he saw me wince in pain. When listening to Absalom, Absalom!, therefore, I felt like I was being stabbed over and over. And if that’s how I felt, imagine the response of a person of color upon encountering a passage like the following, where Quentin imagines young Sutpen, dirt poor, encountering two slaves (a coachman and a butler) of the local plantation owner. It begins when he and his sister are passed by the man’s coach:

[H]e saw two parasols m the carriage and the nigger coachman in a plug hat shouting: ‘Hoo dar, gal! Git outen de way dar!’ and then it was over, gone; the carriage and the dust, the two faces beneath the parasols glaring down at his sister; then he was throwing vain clods of dirt after the dust as it spun on. He knew now, while the monkey-dressed nigger butler kept the door barred with his body while he spoke, that it had not been the nigger coachman that he threw at at all, that it was the actual dust raised by the proud delicate wheels, and just that vain. He thought of one night late when his father came home, blundered into the cabin; he could smell the whiskey even while still dulled with broken sleep, hearing that same fierce exultation, vindication, in his father’s voice; ‘We whupped one of Pettibone’s niggers tonight’ and he roused at that, waked at that, asking which one of Pettibone’s niggers and his father said he did not know, had never seen the nigger before: and he asked what die nigger had done and his father said, ‘Hell fire, that goddam son of a bitch Pettibone’s nigger.’

Quentin has no problem, in his narration, with using the n-word, nor does his Canadian roommate. And in having them discourse this way, Faulkner certainly captures the prevailing mentality, one which persists today. In his recent book The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War, English professor Michael Gora explains what Faulkner still gets right. The saddest words are “was” and “again,” and Gorra writes,

What was is never over. There have been moments in our history, brief ones, when the meaning of the Civil War has seemed settled. This isn’t one of them, not when the illusion that this country might become a postracial society lies in tatters. Again. That’s precisely why Faulkner remains so valuable—that very recurrence makes him necessary.

Necessary though Faulkner is, however, there’s a problem with reading works that only feature the inner turmoil of White characters. That’s why, in literature courses, we must pair figures like Faulkner with authors like Richard Wright, James Baldwin or (my preference) Toni Morrison. If Faulkner explores the continuing impact of our slave past on Whites, Morrison does the same with its impact on Blacks, especially in novels like Beloved and Paradise. Indeed Morrison, who wrote her Master’s thesis in part on Faulkner, can be seen as rounding out his vision.

And how about Huckleberry Finn? Back in the 1990s I had a former student who, grasping the need for such balance, paired Twain’s novel with Morrison’s Song of Solomon in a high school AP class. It was a brilliant coupling since both novels involve young men engaged in journeys of self-discovery. Unfortunately, a White student complained about a couple of pages of Black trash talk in the middle of the novel, prompting the superintendent of schools to ban it. Morrison was dropped from the curriculum while the novel that makes liberal use of the n-word was allowed to stay.

To be clear, I don’t think Huckleberry Finn should be banned for its use of the n-word. It is a brilliant response to the attack on Black rights that a discouraged Twain witnessed when he took a trip down the Mississippi. But it is a White drama, not a Black one. We aren’t able to see in Jim, as we see in Milkman, a Black man negotiating the twin poles of Black surrender to White society and Black violence against it. (Morrison’s protagonist finds a balance.) By banning Morrison, the superintendent made it difficult to do justice to Twain since, without a Black counterbalance, the class itself becomes lopsided.

Black students recognize this to be very much the case when they are only taught To Kill a Mockingbird, which itself features a number of instances of the n-word. While it’s laudable that Atticus schools Scout on its inappropriateness—just as I was schooled those many years ago—the Black characters don’t get the same three-dimensional treatment as the Finch family. As a result, Black students don’t see themselves in the book.

Teachers shouldn’t avoid discussion of the n-word but, as the saying goes, should make the problem the subject. After all, both the word and the attached sentiments are alive and well in present day America. Literature, which immerses us in its world, provides an ideal venue for talking about our racial challenges. But the literature has to be chosen so that multiple parties are heard, not just White ones. It is this multiplicity that is currently under attack in Texas, Florida, and other reactionary states.