Tuesday

I’m currently reading Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman’s Good Omens (1990) in preparation for a Vacation Bible School lecture I will be giving on angels. I’m the third of three lectures on the subject–angels in the Bible, angels in Paradise Lost, and angels in contemporary fantasy—and I’ll share my insights in future posts. For the moment, however, I found a scene that I’m imagining as a comic rendering of Vladimir Putin ordering Russian soldiers into Ukraine.

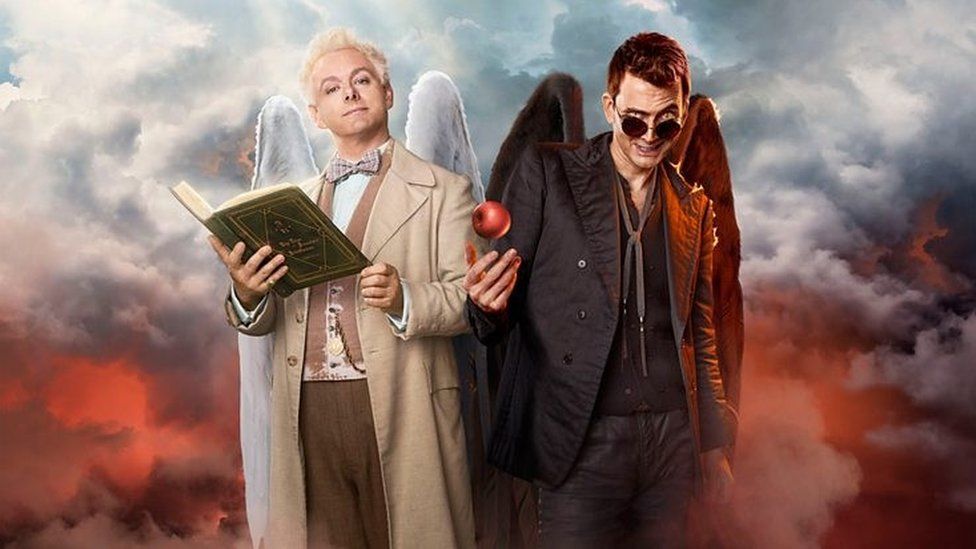

First, a word on Good Omens, which is a remarkable collaboration between two of the greatest contemporary fantasy authors. Pratchett stands out amongst fantasy practitioners since he writes comic fantasy, which is a departure from the deadly serious fantasy that is the norm. (Think Tolkien.) Good Omens has more of a Pratchett than a Gaiman feel to it.

In the novel, the Antichrist has been delivered to an English hospital with the full expectation that he will bring about Armageddon when he grows up. A hospital mix-up, however, means that he is switched with another baby and brought up by a dull tax accountant and his wife. This wreaks havoc with Satan’s plans to have an all-out battle with the Almighty. Issues of nature vs. nurture come to the fore.

Responsible for the mix-up is the fallen angel Crowley, who has been doing Satan’s bidding for centuries. Crowley has become comfortable with his life on earth, however, and isn’t keen on it all coming to an end. He’s even become chummy with Aziraphale, his good angel counterpart, and we learn that he has never been an enthusiastic evil doer: he “did not so much Fall as Saunter Vaguely Downwards.” (Elsewhere we are told, “He hadn’t meant to Fall. He’d just hung around with the wrong people.”) In any event, he now drives around in a Bentley, and his way of causing evil is disrupting everyone’s internet service from time to time.

When the time comes to drop the infant Antichrist off at the hospital, Satan assumes that Crowley will be excited by his chance to bring about the end of the world. I’m thinking that he’s excited in the way that Vladimir Putin is excited at the prospect of recreating the Tsarist empire of the 19th century or the Soviet empire of the 20th. Like many Russians, however, Crowley is less interested in restoring lost glory than in enjoying his comfortable middle-class life. You’ll pick up the discrepancy in enthusiasm levels in their interchange, which occurs over Crowley’s car radio. Satan speaks with the voice of whoever is performing at the time, which in this case happens to be Freddie Mercury of the rock group Queen:

“Ohshitohshitohshit. Why now? Why me?” he muttered, as the familiar strains of Queen washed over him.

And suddenly, Freddie Mercury was speaking to him:

BECAUSE YOU’VE EARNED IT, CROWLEY.

Crowley blessed under his breath. Using electronics as a means of communication had been his idea, and Below had, for once, taken it up and, as usual, got it dead wrong. He’d hoped they could be persuaded to subscribe to Cellnet, but instead they just cut in to whatever it happened to be that he was listening to at the time and twisted it.

Crowley gulped.

“Thank you very much lord,” he said.

WE HAVE GREAT FAITH IN YOU, CROWLEY.

“Thank you, lord.”

THIS IS IMPORTANT, CROWLEY.

“I know, I know.”

THIS IS THE BIG ONE, CROWLEY.

“Leave it to me, lord.”

THAT IS WHAT WE ARE DOING, CROWLEY, AND IF IT GOES WRONG, THEN THOSE INVOLVED WILL SUFFER GREATLY. EVEN YOU, CROWLEY. ESPECIALLY YOU.

“Understood, lord.”

HERE ARE YOUR INSTRUCTIONS, CROWLEY.

And suddenly he knew. He hated that. They could just as easily have told him, they didn’t suddenly have to drop chilly knowledge straight into his brain. He had to drive to a certain hospital.

“I’ll be there in five minutes, lord, no problem.”

As it turns out, Crowley’s mission doesn’t go any better than Putin’s as both Earth and Ukraine survive to live another day. Moral: Don’t expect success when you lack buy-in from your followers.

Further application: While the Antichrist is growing up, the four horsemen of the Apocalypse—make that the four horsepersons—are assembling. War is an arms dealer named Scarlett, who has auburn hair that “fell to her waist in tresses that men would kill for, and indeed often had.” We see a before and after description of “Kubolaland” that vaguely resembles Ukraine before and after the February 24 Russian invasion. Here’s before:

She was in the middle of a city at the time. The city in question was the capital of Kumbolaland, an African nation which had been at peace for the lat three thousand years. For about thirty years it was Sir-Humphrey-Clarksonland, but since the country had absolutely no mineral wealth and the strategic importance of a banana, it was accelerated toward self-government with almost unseemly haste. Kumbolaland was poor, perhaps, and undoubtedly boring, but peaceful. Its various tribes, who got along with one another quite happily, had long since beaten their swords into ploughshares; a fight had broken out in the city square in 1952 between a drunken ox-drover and an equally drunken ox-thief. People were still talking about it.

The Scarlett shows up, at which point all humor leaves the narrative:

She looked around the street: a couple of women chatted on a street corner; a bored market vendor sat in front of a heap of colored gourds, fanning the flies; a few children played lazily in the dust.

“What the hell,” she said quietly. “I could do with a holiday anyway.”

That was Wednesday.

By Friday the city was a no-go area.

By the following Tuesday the economy of Kumbolaland was shattered, twenty thousand people were dead…, almost a hundred thousand people were injured, all of Scarlett’s assorted weapons had fulfilled the function for which they had been created, and the vulture had died of Greasy Degeneration.

When it comes to Vladimir Putin and all other “masters of war,” the anger of Bob Dylan’s song is only too appropriate:

Let me ask you one question

Is your money that good?

Will it buy you forgiveness

Do you think that it could?

I think you will find

When your death takes its toll

All the money you made

Will never buy back your soul