Thursday

Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky has a moving essay in Oprah Daily on the necessity of poetry in tough times. In it, he tells the story of a friend who, while spending whole nights in Kyiv subway stations serving as bomb shelters, has taken to

reciting poems to herself and those around her to keep sane. When she grows tired, she starts translating those poems into other languages, just as a way of keeping going.

Her story prompts Kaminsky to observe,

Critics in the West often ask whether poetry matters. I now realize that the only valid response to this question is: Do such critics matter? If a person sheltering deep underground as her city is bombed recites poems as a survival tool—to soothe herself and others—that is all the evidence I need that poetry matters.

And then he adds,

But we humans always knew that.

Yes, we always have known that. It’s just that sometimes we need reminding. I, of course, seek to remind you daily of this. But my reminders don’t have the fierce urgency that Kaminsky has as he reports experiences of poet friends still in Ukraine.

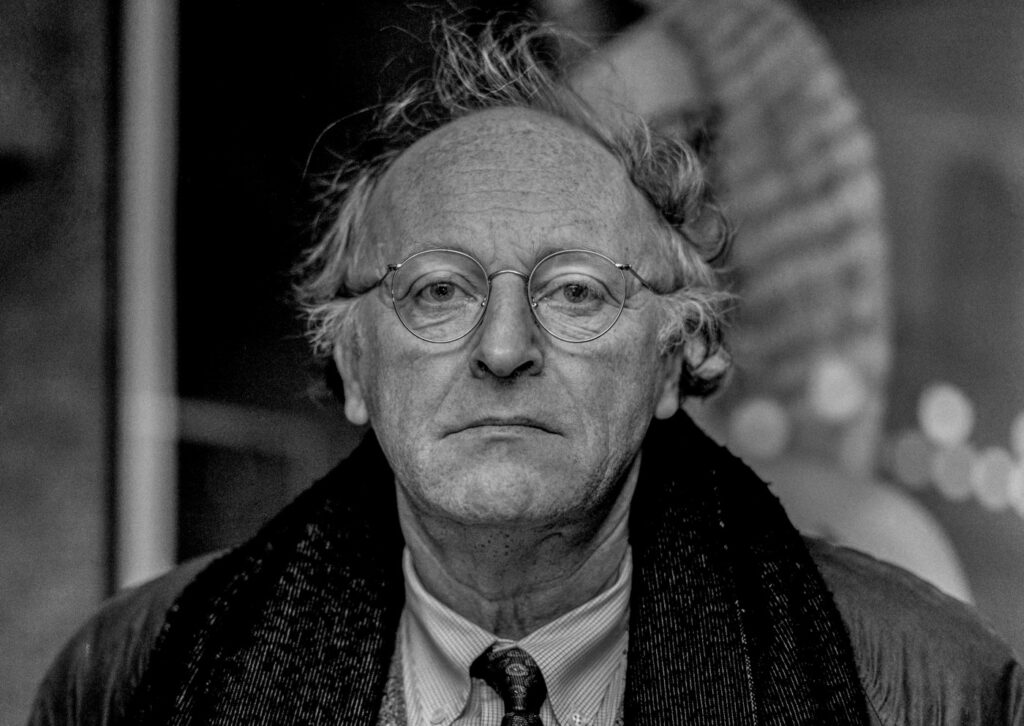

For instance, there’s his friend from Kharkiv, Anastasia Afanasieva, who “took a long break from poetry” to set up a successful business selling fishhooks but, with Russian bombs now having destroyed the business, she’s back to writing poetry again. Although in the past she won two of Russia’s top awards for poetry, Afanasieva has now shifted to Ukrainian. One poem, where she describes the decision, begins in Russian but shifts to her national language midway through.

Kaminsky quotes from her e-mail to him, which he observes reads at time like a prose poem:

Since the war started, I feel it’s like one long day: I still don’t know what day of the week it is or what date. The past was cancelled in one minute. Imagine a magic eraser, which erases all the text in one moment from the paper—and paper becomes white as a new snow. Personal past is no more. No former goals, no former job, no former habits, no former stores we used to visit for groceries every day, no former walking routes, no former landscapes, no home, no former dreams—pure nothing. You’re born again at the age of 40—having only a book of memories with you, a book, which you read till the end and there are no new chapters. And you, like a newborn, try to learn to walk and speak again.

“Poetry,” Kaminsky concludes,

now is as necessary as ever. Not because it is pretty or fancy. But because it helps us to articulate the most impossible moments: It gives us a gasp, a scrap of air in our lungs. When we have nothing else, we can still hold a handful of words in our memory, a tune, and that might be all we have got now to survive—we don’t know yet. But if we are lucky, it is there.

And then he leaves off with this advice:

Keep it safe, this verbal music. Memorize new line poems if you can. You might need them one day, war planes or not. When facing the blank wall that is crisis, everyone needs a bit of music, a tune, a balm.

During the German blitzkrieg of 1940 and 1941, London bookstores apparently sold out their poetry. If there are any bookstores left intact in Ukraine, I suspect they have as well.

Additional Afanasieva poem: I believe the following poem, translated from the Russian by Olga Livshin and Andrew Janco, was written after the Russian invasion of Ukraine’s Crimea region in 2014. Reading it now, one thinks of those Ukrainian refugees who, having escaped to the west, are now returning home, in spite of the danger. As the poem notes, people sometimes hear a call that overrides all other considerations:

That’s my home. . .

1

That’s my home.

There was a bridge here.

Now there isn’t.That’s my home.

That’s my yard.

It’s still here.Where a bridge stood,

there’s a river.

No more bridge.Where there was once a pass,

now there’s a line.We live here,

on the line.In the devil’s belly,

that’s where.2

I came back

Barely made it

Took a while to get everyone out

I have a big family

My parents are old

Then there are my

Brother my sister my

pregnant daughter

I got them all out

Out of that damned house

Just imagine

There’s a river

There was a bridge there

Now it’s destroyed

On the one side of the river these people

On the other side, those

Whoever they are

Between them, our house

It took me so many trips

There and back

For each person

I barely got them out

A big family

These on the one side, those on the other

The house stands like a shadow

As though lead passes through the walls

Or the house contorts its beams

So that it can dodge the hail of bullets

It twists left and right

What it took me, a woman

To get all of them out

You can’t imagine

One by one

Right from the belly of the beast

Coming back every time,

Diving into all of that,

Not knowing

If there will be a way

But I got them all out

And now my daughter

Yes, the pregnant one

Says she wants to return

She’s headed back tomorrow

She has someone there

A man she loves

See, he stayed back there

And love, well

You know how love goes

With those young people

You know how it is for them

Anything for love