Tuesday

Having written yesterday about Kenosha shooter Kyle Rittenhouse, I turn today to the Ahmaud Arbery killers, who themselves are in the final stages of their trial. The three men, two of them armed, chased the jogging Abery in two trucks, cutting him off. Because he then attacked them, they are now, like Rittenhouse, pleading self-defense. They also are claiming that they tried to make a citizen’s arrest on the grounds that Arbery, being black, must have had something to do with past thefts in the neighborhood.

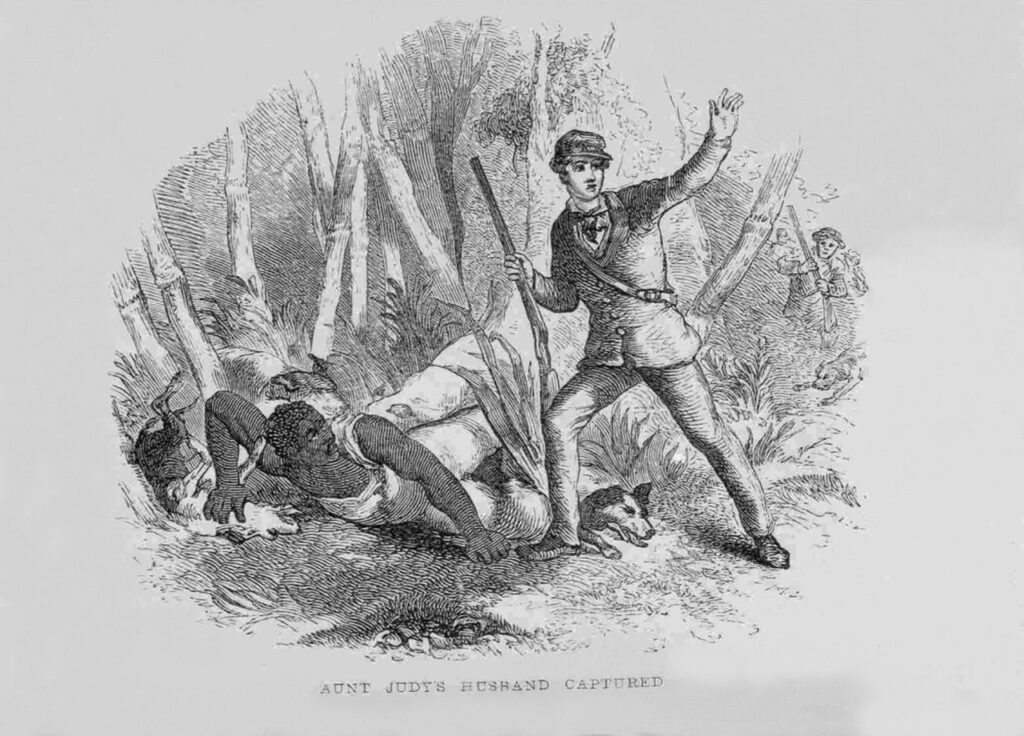

As many have noted, the killing resembled an old-fashioned lynching, and there’s another disturbing connection with the past: they resembled slave catchers from pre-Civil War days, chasing down a fleeing black man because of his skin color.

When I heard an MSNBC commentator make this comparison, I thought of the slave catchers in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Eliza, her newborn child, her husband George, and others are involved in a breathtaking chase with violent and lecherous vigilantes on their heels. Fortunately, unlike Arbery, they manage to escape, in part because they have their own guns:

Another hill, and their pursuers had evidently caught sight of their wagon, whose white cloth-covered top made it conspicuous at some distance, and a loud yell of brutal triumph came forward on the wind. Eliza sickened, and strained her child closer to her bosom; the old woman prayed and groaned, and George and Jim clenched their pistols with the grasp of despair. The pursuers gained on them fast…

At this point, the slaves leave the wagon and flee into the hills. Their Quaker guide, Phineas Fletcher, takes them along a narrow ledge, which puts them in a position to defend themselves:

A few moments’ scrambling brought them to the top of the ledge; the path then passed between a narrow defile, where only one could walk at a time, till suddenly they came to a rift or chasm more than a yard in breadth, and beyond which lay a pile of rocks, separate from the rest of the ledge, standing full thirty feet high, with its sides steep and perpendicular as those of a castle. Phineas easily leaped the chasm, and sat down the boy on a smooth, flat platform of crisp white moss, that covered the top of the rock.

“Over with you!” he called; “spring, now, once, for your lives!” said he, as one after another sprang across. Several fragments of loose stone formed a kind of breast-work, which sheltered their position from the observation of those below.

The pursuers show the same kind of confidence that Arbery’s killers may have exhibited as they closed in on him:

“Well, Tom, yer coons are farly treed,” said one [of the slave catchers].

“Yes, I see ’em go up right here,” said Tom; “and here’s a path. I’m for going right up. They can’t jump down in a hurry, and it won’t take long to ferret ’em out.”

Then follows a verbal exchange in which escaped slave George Harris exposes America’s justice system of the time:

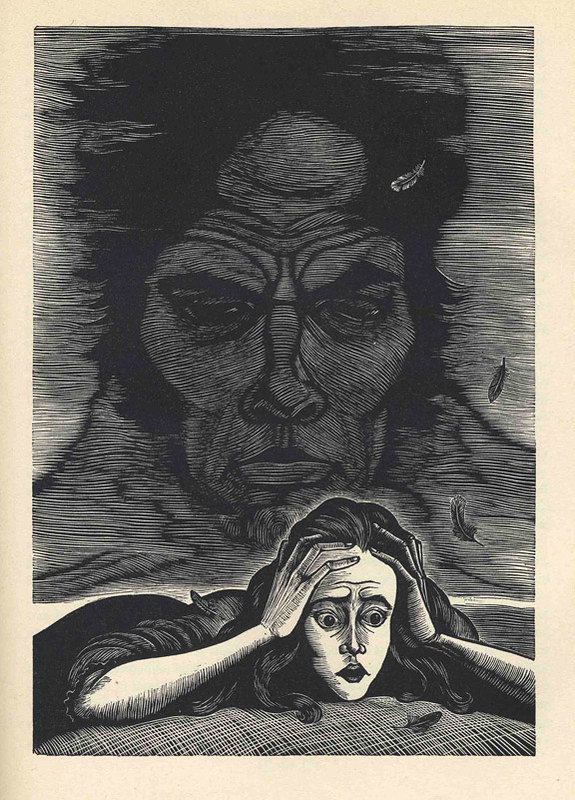

At this moment, George appeared on the top of a rock above them, and, speaking in a calm, clear voice, said,

“Gentlemen, who are you, down there, and what do you want?”

“We want a party of runaway niggers,” said Tom Loker. “One George Harris, and Eliza Harris, and their son, and Jim Selden, and an old woman. We’ve got the officers, here, and a warrant to take ’em; and we’re going to have ’em, too. D’ye hear? An’t you George Harris, that belongs to Mr. Harris, of Shelby county, Kentucky?”

“I am George Harris. A Mr. Harris, of Kentucky, did call me his property. But now I’m a free man, standing on God’s free soil; and my wife and my child I claim as mine. Jim and his mother are here. We have arms to defend ourselves, and we mean to do it. You can come up, if you like; but the first one of you that comes within the range of our bullets is a dead man, and the next, and the next; and so on till the last.”

“O, come! come!” said a short, puffy man, stepping forward, and blowing his nose as he did so. “Young man, this an’t no kind of talk at all for you. You see, we’re officers of justice. We’ve got the law on our side, and the power, and so forth; so you’d better give up peaceably, you see; for you’ll certainly have to give up, at last.”

“I know very well that you’ve got the law on your side, and the power,” said George, bitterly. “You mean to take my wife to sell in New Orleans, and put my boy like a calf in a trader’s pen, and send Jim’s old mother to the brute that whipped and abused her before, because he couldn’t abuse her son. You want to send Jim and me back to be whipped and tortured, and ground down under the heels of them that you call masters; and your laws will bear you out in it,—more shame for you and them! But you haven’t got us. We don’t own your laws; we don’t own your country; we stand here as free, under God’s sky, as you are; and, by the great God that made us, we’ll fight for our liberty till we die.”

George stood out in fair sight, on the top of the rock, as he made his declaration of independence; the glow of dawn gave a flush to his swarthy cheek, and bitter indignation and despair gave fire to his dark eye; and, as if appealing from man to the justice of God, he raised his hand to heaven as he spoke.

Thanks to the Fugitive Slave Law, which allowed slave catchers to pursue slaves in non-slave America, the law is in fact on the side of the pursuers. As we see when juries rule in favor of cops and White vigilantes who shoot Black men, too often it continues to be on the side of today’s pursuers. If it weren’t for video footage of the Arbery slaying, his killers might be walking around free today. As we await the jury’s verdict, we’ll learn soon how much—or how little—we have progressed from the justice of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s day.

Further thought: At one point in her narrative Stowe unleashes her bitter sarcasm upon the slave catchers and slave traders, who she notes are on their way to evolving from human scum to respected civic leaders:

If any of our refined and Christian readers object to the society into which this scene introduces them, let us beg them to begin and conquer their prejudices in time. The catching business, we beg to remind them, is rising to the dignity of a lawful and patriotic profession. If all the broad land between the Mississippi and the Pacific becomes one great market for bodies and souls, and human property retains the locomotive tendencies of this nineteenth century, the trader and catcher may yet be among our aristocracy.

Whether the catchers have become our aristocracy is debatable, but historians have drawn lines from slave catchers to southern Klansmen to today’s racist police.