Friday

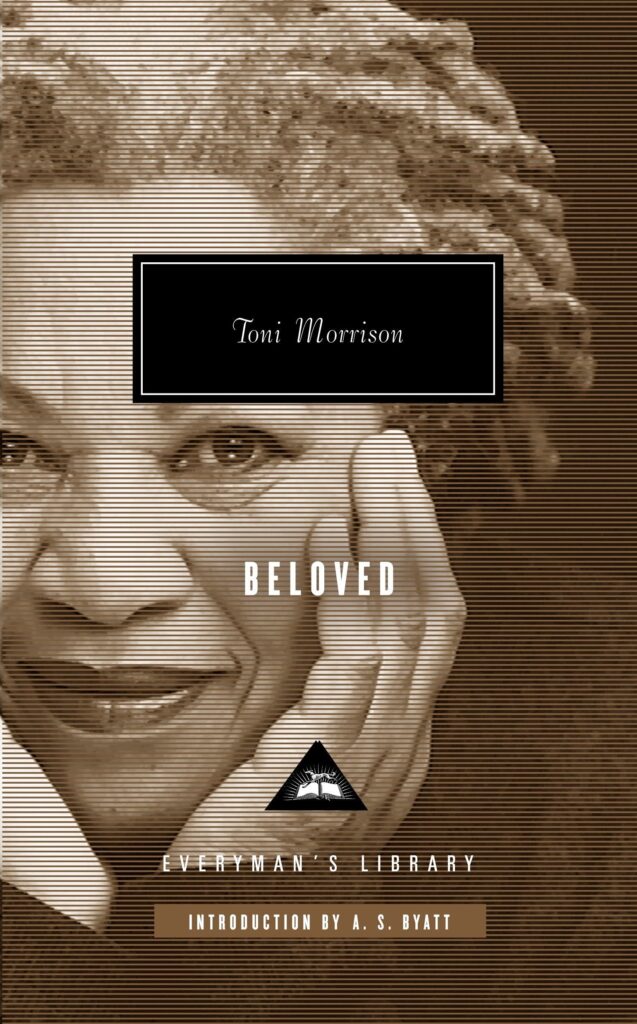

It stands to reason that, following their war with America’s scientists and doctors, America’s rightwing would next go after teachers and school librarians. One assault is occurring in the Goddard School District in Kansas, which has directed its school libraries not to check out 29 books, including Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, and August Wilson’s 1987 Pulitzer-prize winning drama Fences.

KMUW reports that Julie Cannizzo, Goddard’s assistant superintendent for academic affairs in Goddard, sent out the following e-mail along with the list:

“At this time, the district is not in a position to know if the books contained on this list meet our educational goals or not,” Cannizzo wrote in the email. “Additionally, we need to gain a better understanding of the processes utilized to select books for our school libraries.

“For these reasons, please do not allow any of these books to be checked out while we are in the process of gathering more information. If a book on this list is currently checked out, please do (not) allow it to be checked out again once it’s returned.”

According to KMUW, the e-mail also noted that

the district is assembling a committee to “rate the content of the books on the list” and to review the selection process. She did not say how long the process is expected to take.

Here’s the complete list:

#MurderTrending by Gretchen McNeil

All Boys Aren’t Blue, George M. Johnson

Anger Is a Gift, Mark Oshiro

Black Girl Unlimited, Echo Brown

Blended, Sharon M. Draper

Crank, Ellen Hopkins

Fences, August Wilson

A Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, Alison Bechdel

Gender Queer, Maia Kobabe

Heavy, Kaise Laymon

Lawn Boy, Jonathan Evison

Lily and Dunkin, Donna Gephart

Living Dead Girl, Elizabeth Scott

Monday’s Not Coming, Tiffany D. Jackson

Out of Darkness, Ashley Hope Perez

Satanism, Tamara L. Roleff

The 57 Bus: A True Story of Two Teenagers and the Crime that Changed Their Lives, Dashka Slater

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, Sherman Alexie

The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison

The Girl Who Fell from the Sky, Heidi W. Durrow

The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood

The Handmaid’s Tale: The Graphic Novel, adapted by Renee Nault

The Hate U Give, Angie Thomas

The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Stephen Chbosky

The Testaments, Margaret Atwood

They Called Themselves the K.K.K.: The Birth of an American Terrorist Group, Susan Campbell Bertoletti

The Book Is Gay, James Dawson

This One Summer (graphic novel), Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki

Trans Mission: My Quest to a Beard, Alex Bertie

Given the apparent success of Virginia gubernatorial candidate Glenn Youngkin’s attack on Morrison’s Beloved, I fully expect such lists to become the norm in Republican districts across the country. The trend also makes a lot of sense: if your intention is to take down America’s Enlightenment project, then few things stand in your way more than public education, public libraries, and novels.

In some ways, I’m amazed that teachers and school libraries have gotten away with offering these books for as long as they have. Literature, as I said in a recent post, is like a loaded gun, with the potential to shatter myths and stereotypes. For parents who want to turn out young people exactly like themselves—who think and behave exactly like they do—novels and poems are the enemy. Educators have been handling literary dynamite for a while now, and until recently, parental indifference—at least the indifference of certain parents—has been their friend. English teachers have been seen as just teaching stories, and what harm can stories do?

All that may be about to change as we see educators (I include librarians under that label) suffering the same attacks as medical professionals. Who knew that recommending a mask to protect others would suddenly have angry citizens shouting, “We know where you live!”? Doctors and nurses, like climate scientists before them, have learned that they can’t stay aloof from politics. When your very approach to the world is seen as political, then you have to figure out how to be political in return. The key is to be smart about it.

In some ways, the problem is that educators have become more responsive to kids’ needs, as have the authors of many of the books being banned. When I was a child and a teenager, our teachers didn’t concern themselves with the books we needed to negotiate life’s challenges. They assigned canonical texts which, because they had been written long ago, weren’t seen as having much to do with actual life. Literature was a comfortably boring subject.

Now, however, we are living in the golden age of Young Adult Fiction, and one finds novels exploring every aspect of teenage life—and often getting attacked and even banned as a result. Add to this how much more complicated the world has become and the conditions are ripe for parents lashing out. They are afraid of the world their children are entering, even as their children are hungry for the information that these novels provide.

I wrote recently about a Texas legislator compiling a list of 800+ books that he wants investigated, including John Irving’s Cider House Rules. He’ll want banned any books that

contain material that might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex or convey that a student, by virtue of their race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.

To that story we can now add another, this one in northern Virginia, where school board members want books not only banned but burned. The Washington Post reports,

Shortly after the election result in Virginia, a pair of conservative school board members in the same state proposed not just banning certain books deemed to be sexually explicit, but burning them.

As the Fredericksburg Free-Lance Star reported Tuesday:

Two board members, Courtland representative Rabih Abuismail and Livingston representative Kirk Twigg, said they would like to see the removed books burned.

“I think we should throw those books in a fire,” Abuismail said, and Twigg said he wants to “see the books before we burn them so we can identify within our community that we are eradicating this bad stuff.”

Abuismail reportedly added that allowing one particular book to remain on the shelves even briefly meant the schools “would rather have our kids reading gay pornography than about Christ.”

Do you remember the good old days when Republicans excoriated a publisher for choosing not to continue publishing certain obscure Doctor Seuss books for their racist caricatures. Lambasting liberals for “cancel culture” was all the rage then. America’s rightwing extremists, it’s now clear, have never believed in free speech. They’re willing to allow only speech that agrees with them.