Tuesday

My recent reading has given me a case of emotional whiplash as I’ve moved from two Jo Nesbo serial killer mysteries to Virginia Woolf’s The Voyage Out. I decided to give Nesbo a try after reading about “Nordic noir” so I randomly googled practitioners of the form and came up with the Norwegian author. I’ve read The Snowman and The Leopard and am now sorry I did so.

Switching over to Voyage Out, one of the few Woolf novels I haven’t read, was surreal. After having watched various women get tortured in gruesome ways, along with men proving their manhood, I needed something to wash the sadism and misogyny out of my mind. So I turned from dick lit to chick lit. Except that Woolf isn’t chick lit.

My initial impression is that nothing is happening. To be sure, I’m still in the early chapters, but cultivated Brits having random conversations as they boat around the Mediterranean is a long way from killing people with spiked balls that explode in the mouth and dissecting them with red hot wire. Where’s the plot, I found myself wondering.

After Woolf reprogrammed me to accept her leisurely pace, however, I felt at home. I especially enjoy a conversation about literature between Clarissa Dalloway and a young musician she has met on board ship. Clarissa has just interrupted Rachel while she is practicing the piano, and Rachel clears a chair for her to sit down:

She slid Cowper’s Letters and Wuthering Heights out of the arm-chair, so that Clarissa was invited to sit there.

“What a dear little room!” she said, looking round. “Oh, Cowper’s Letters! I’ve never read them. Are they nice?”

“Rather dull,” said Rachel.

“He wrote awfully well, didn’t he?” said Clarissa; “—if one likes that kind of thing—finished his sentences and all that. Wuthering Heights! Ah—that’s more in my line. I really couldn’t exist without the Brontes! Don’t you love them? Still, on the whole, I’d rather live without them than without Jane Austen.”

Lightly and at random though she spoke, her manner conveyed an extraordinary degree of sympathy and desire to befriend.

“Jane Austen? I don’t like Jane Austen,” said Rachel.

“You monster!” Clarissa exclaimed. “I can only just forgive you. Tell me why?”

“She’s so—so—well, so like a tight plait,” Rachel floundered.

Rachel’s comment reminds me of what Charlotte Bronte said about Pride and Prejudice when reviewer George Lewes held it up to her as a model. Although Lewes wrote a positive review of Jane Eyre, he was put off by what he saw as its melodrama, especially the gothic parts involving the mad woman in the attic. Bronte responded that essentially Austen doesn’t have enough melodrama:

I got the book and studied it. And what did I find? An accurate daguerreotyped portrait of a common-place face; a carefully fenced, highly cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers—but no glance of a bright vivid physiognomy—no open country—no fresh air—no blue hill—no bonny beck. I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen in their elegant but confined houses.

And in another letter:

The Passions are perfectly unknown to her.

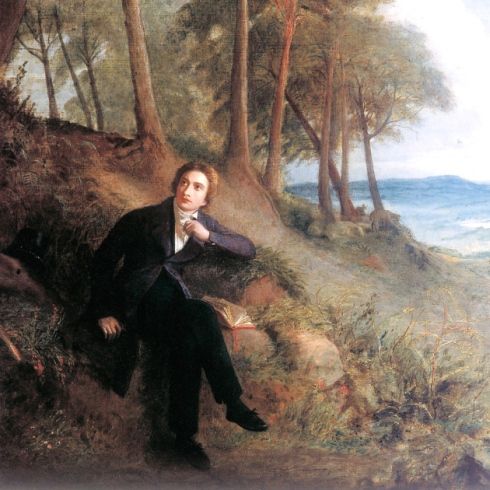

There is something Austen-esque in Clarissa Dalloway, which she attributes to being older. She remembers being drawn to Adonais, Percy Shelley’s passionate elegy on Keats, as a young woman:

“Ah—I see what you mean. But I don’t agree. And you won’t when you’re older. At your age I only liked Shelley. I can remember sobbing over him in the garden.

He has outsoared the shadow of our night,

Envy and calumny and hate and pain—you remember?

Can touch him not and torture not again

From the contagion of the world’s slow stain.How divine!—and yet what nonsense!” She looked lightly round the room. “I always think it’s living, not dying, that counts.

I shudder to think how Shelley, who lived life at the stretch and who once wrote, “I fall upon the thorns of life, I bleed,” would respond to Clarissa’s next observation:

I really respect some snuffy old stockbroker who’s gone on adding up column after column all his days, and trotting back to his villa at Brixton with some old pug dog he worships, and a dreary little wife sitting at the end of the table, and going off to Margate for a fortnight—I assure you I know heaps like that—well, they seem to me really nobler than poets whom every one worships, just because they’re geniuses and die young. But I don’t expect you to agree with me!”

She pressed Rachel’s shoulder.

“Um-m-m—” she went on quoting—

Unrest which men miscall delight—

“when you’re my age you’ll see that the world is crammed with delightful things. I think young people make such a mistake about that—not letting themselves be happy. I sometimes think that happiness is the only thing that counts. I don’t know you well enough to say, but I should guess you might be a little inclined to—when one’s young and attractive—I’m going to say it!—everything’s at one’s feet.”

In The Company We Keep, theorist Wayne Booth differentiates great literature from popular literature on the grounds than the former prompts us to desire better desires. It expands or (as Lisa Simpson would say) embiggens us. I don’t feel embiggened by Nesbo’s Nordic noir whereas, in Voyage Out, I watch people’s faltering but genuine attempts to imagine something bigger than themselves.

Woolf doesn’t get the blood pumping in the same way as Nesbo. I find her fiction ultimately more invigorating, however.