Spiritual Sunday

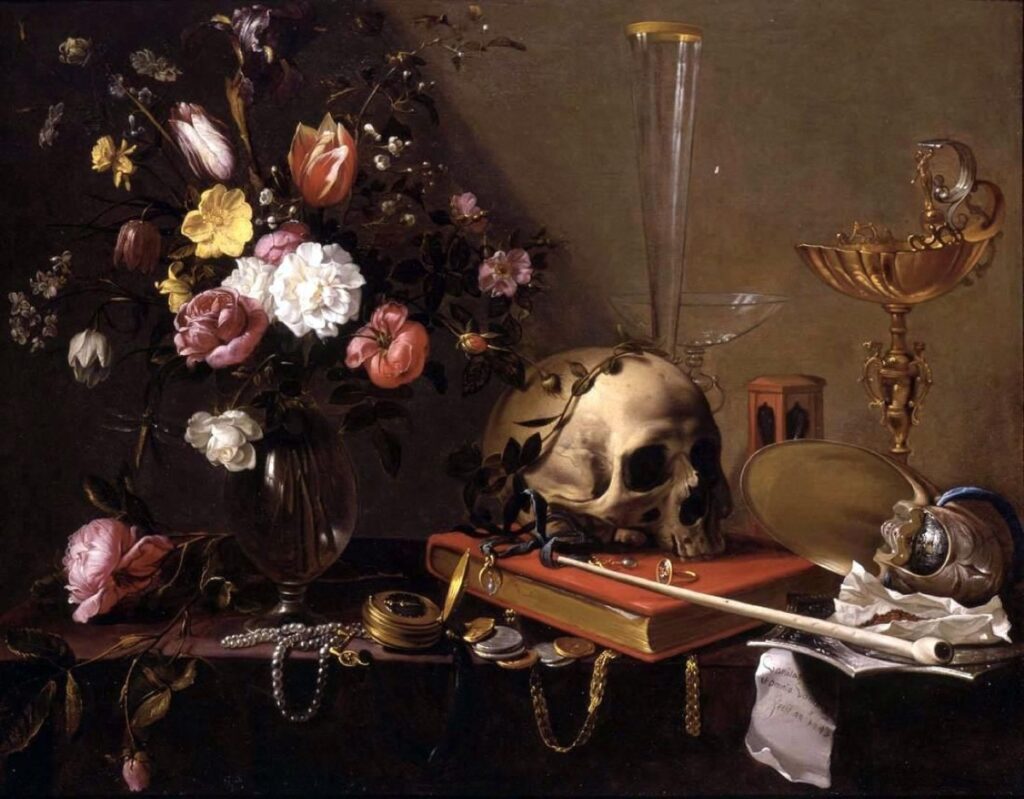

I would never think of associating Henry David Thoreau with George Hebert, but I’ve come across some poems written very much in Herbert’s spirit in Harold Bloom’s American Religious Poems. Herbert grapples with doubt in many of his poems (for instance, “Denial”), and “Sic Vita” (such is life) conveys its own sense of human frailty. Thoreau dwells upon a bouquet of hastily plucked flowers that will wither quickly because they have been separated from their creator.

I did some research into the poem and learned that Branson Alcott, father of Louis Mae, read the poem at Thoreau’s funeral. In one way, this seems appropriate: while we may droop here on earth, the poet is reassured that “I was not plucked for nought” but was brought by a “kind hand” to a “strange place.”

I find the poem to be more ambiguous than that, however. First of all, it ends on a down note (“while I droop here), to be ambiguous. When Thoreau says that God will replenish the stock with “more fruits and fairer flowers,” is he saying that he will return to the original garden? Or just that God will keep sending “more fruits and fairer flowers” to perish here, like a callous general sending his men into cannon fire? The reference to God as a “kind hand” argues against this, but still I wonder.

Or is Thoreau hinting at the vegetation cycle of life here, which can differ from Christianity’s eschatological vision that we are headed toward an end point? As in, “we may be part of the stock that is thinned, but God/nature will keep sending replacements.” This view is reassuring if one sees oneself as part of “the perfect whole” (as Thoreau’s friend Ralph Waldo Emerson does in “Each and All”), but less so if one focuses on oneself as an individual, as Thoreau seems to do in the last line.

In puzzling over this ambiguity, I think of how Thoreau’s vision contrasts with a Henry Vaughan poem that “Sic Vita” also reminds me of. Talking of being placed in “life’s vase,” and therefore having a brief time to live, Thoreau writes of being set in glass while still alive. Vaughan mentions a different kind of glass–glass to help us see better–in the concluding stanza of “They Are All Gone into the World of Light”:

Either disperse these mists, which blot and fill

My perspective still as they pass,

Or else remove me hence unto that hill,

Where I shall need no glass.

Vaughan seems confident that he will see God face to face, like those before him who have gone before him, and his poem ends on a high note. Thoreau’s glass, however, separates him from that which replenishes life rather than giving him a sense, however vague, of divinity. He’s not climbing a final hill but drooping.

Anyway, Thoreau’s struggle for meaning is striking with its organizing metaphor of plucked flowers. Let me know what you think.

Sic Vita

By Henry David Thoreau

(“It is but thin soil where we stand; I have felt my roots in a richer ere this. I have seen a bunch of violets in a glass vase, tied loosely with a straw, which reminded me of myself”

— A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers)

I am a parcel of vain strivings tied

By a chance bond together,

Dangling this way and that, their links

Were made so loose and wide,

Methinks,

For milder weather.

A bunch of violets without their roots,

And sorrel intermixed,

Encircled by a wisp of straw

Once coiled about their shoots,

The law

By which I’m fixed.

A nosegay which Time clutched from out

Those fair Elysian fields,

With weeds and broken stems, in haste,

Doth make the rabble rout

That waste

The day he yields.

And here I bloom for a short hour unseen,

Drinking my juices up,

With no root in the land

To keep my branches green,

But stand

In a bare cup.

Some tender buds were left upon my stem

In mimicry of life,

But ah! the children will not know,

Till time has withered them,

The woe

With which they’re rife.

But now I see I was not plucked for naught,

And after in life’s vase

Of glass set while I might survive,

But by a kind hand brought

Alive

To a strange place.

That stock thus thinned will soon redeem its hours,

And by another year,

Such as God knows, with freer air,

More fruits and fairer flowers

Will bear,

While I droop here.