Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Friday

For much of this week I have been reposting essays from this past year about how literature can be a comfort, support,and guide in dark times. I’m struck by how literature reinforces a recent set of tips on how to keep democracy alive, courtesy of American philosopher and linguist George Lakoff.

Among these tips are: be brave, cultivate empathy, stay focused, foster real connections, avoid brain rot and lies, demand accountability, and support artists and the arts. Great literature touches on all these areas in one way or another, providing us with forums where courage, truth, and justice are prized, where accountability is demanded, where empathy is fostered, and where focus is required. The best poems, plays, and stories engage our best and fullest selves, providing us with a lodestar that will direct our steps when we find ourselves faltering.

This past July, looking for a pick-me-up, I turned to Samuel Johnson’s philosophic novel Rasselas: A Prince of Abyssinia. The following essay was the result.

Reprinted from July 12, 2024

Uncertainty about the 2024 election is driving Democrats mad at the moment. Why does the race continue so close, we wonder, given that Joe Biden has created a stellar economy while Donald Trump attempted a coup and is now—with his threats of retribution and Project 2025—promising a fascist takedown of American democracy if reelected? While the situation is worrisome, however, worrying ourselves sick over the matter is not going to change things.

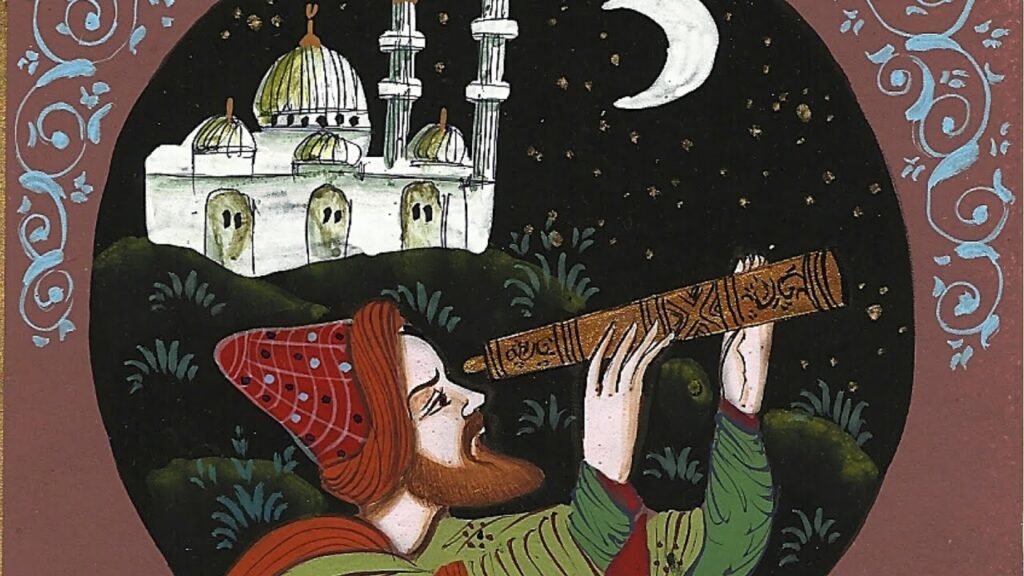

When I find myself consumed by despair over this state of affairs, I sometimes think of Samuel Johnson’s astronomer in his philosophic novel Rasselas.

Rasselas is on a journey to discover the secret of happiness and thinks he has found it in a learned scientist who has given over his life to studying the heavens. This man spends as much time charting interstellar space as political junkies spend surfing the internet, a comparison I make because similar results ensue. First, here’s Rasselas’s mentor Imlac reporting on the astronomer:

I have just left the observatory of one of the most learned astronomers in the world, who has spent forty years in unwearied attention to the motion and appearances of the celestial bodies, and has drawn out his soul in endless calculations.

And now here’s the result, which Imlac discovers after noticing the astronomer’s depression and pressing him on it. The astronomer reveals that he does not possess the key to happiness after all:

Hear, Imlac, what thou wilt not without difficulty credit. I have possessed for five years the regulation of the weather and the distribution of the seasons. The sun has listened to my dictates, and passed from tropic to tropic by my direction; the clouds at my call have poured their waters, and the Nile has overflowed at my command. I have restrained the rage of the dog-star, and mitigated the fervors of the crab. The winds alone, of all the elemental powers, have hitherto refused my authority, and multitudes have perished by equinoctial tempests which I found myself unable to prohibit or restrain. I have administered this great office with exact justice, and made to the different nations of the earth an impartial dividend of rain and sunshine. What must have been the misery of half the globe if I had limited the clouds to particular regions, or confined the sun to either side of the equator?

Just like many who follow the ups and downs of politics, the astronomer doesn’t differentiate between worrying about cataclysmic events and having actual control over them. And while he acknowledges he can’t prove his power, he trusts his vibes:

I…shall not attempt to gain credit by disputation. It is sufficient that I feel this power that I have long possessed, and every day exerted it.

After describing the encounter, Imlac warns the Rasselas party,

He who has nothing external that can divert him must find pleasure in his own thoughts, and must conceive himself what he is not; for who is pleased with what he is? He then expatiates in boundless futurity, and culls from all imaginable conditions that which for the present moment he should most desire…and confers upon his pride unattainable dominion.

The problem is particularly acute, Imlac says, for those who have a strong sense of responsibility and who feel guilty for not doing more:

“No disease of the imagination,” answered Imlac, “is so difficult of cure as that which is complicated with the dread of guilt; fancy and conscience then act interchangeably upon us, and so often shift their places, that the illusions of one are not distinguished from the dictates of the other….[W]hen melancholy notions take the form of duty, they lay hold on the faculties without opposition, because we are afraid to exclude or banish them.

Those who take their citizenship duties seriously may find conscience mixing with fantasies of power—we all have them—and consequently finding themselves plunged into melancholy or depression.

So what is to be done? Part of the problem is solitude, so Rasselas and his party pull the astronomer out of his observatory and get him to join them in a variety of activities, which include conversing with their lovely handmaiden Pekulah. In other words, they offer him perspective and a sense of proportion. Once they do, he comes to realize that he is doesn’t carry the whole weight of the world on his shoulders. As Imlac sums it up,

Open your heart to the influence of the light, which from time to time breaks in upon you; when scruples importune you, which you in your lucid moments know to be vain, do not stand to parley, but fly to business or to Pekuah; and keep this thought always prevalent, that you are only one atom of the mass of humanity, and have neither such virtue nor vice as that you should be singled out for supernatural favors or afflictions.

For concerned citizens, flying to business can include contacting members of Congress, writing postcards, knocking on doors, and donating money, and of course voting. Other versions of flying to Pekuah, meanwhile, include romantic outings, partying with friends, exercising, and so on. The key is stepping away from the black hole that is the political internet.

This remedy works with the astronomer, who reflects,

I now see how fatally I betrayed my quiet, by suffering chimeras to prey upon me in secret…I hope that time and variety will dissipate the gloom that has so long surrounded me, and the latter part of my days will be spent in peace.

To which Imlac replies, “Your learning and virtue may justly give you hopes.”