Wednesday

To address the issue of unchecked police behavior, I am repurposing a blog essay I wrote on H.G. Wells’s Invisible Man in December, 2017. At the time, the GOP was planning massive tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans that would blow up the deficit while providing peanuts for everyone else. As I noted, they appeared to have learned a version of Trump’s Access Hollywood pronouncement, “And when you’re a star, they let you [kiss beautiful women]. You can do anything… Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything.” Same with the GOP, when you control all levels of government and have dispensed with normal checks and balances, you can do anything.

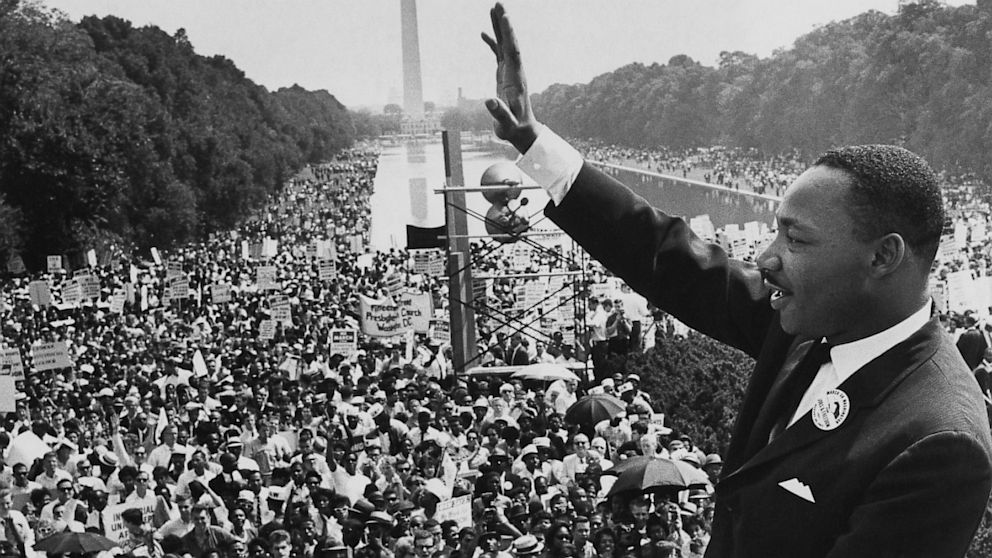

Similarly, if the misconduct of racist cops is routinely buried so that they can shove, beat and even kill people with impunity, they will inevitably do so. I see that, in response to public pressure, the New York legislature has just voted to make cop disciplinary records public for the first time in 50 years.

Few maxims are truer than “Power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely.” It’s no accident that, upon learning the secret of invisibility, Wells’s protagonist immediately starts violating social norms. It’s an aspect of human nature that Plato explores in the Gyges ring parable that inspired Wells’s story.

The parable appears in Book 2 of The Republic. Arguing with Socrates that people behave justly only because they fear the consequences of not doing so, Glaucon recounts how the shepherd Gyges, after finding a ring that renders him invisible, proceeds to seduce the queen, murder the king, and become king himself. While people might publicly applaud a good man that didn’t take advantage of such a ring, Glaucon states that they would in actuality regard him as a fool.

Rather than such freedom making Gyges happy, Socrates counters that he will always be slave to his appetites. While I believe this to be true, this is of scant consolation to Gyges’s victims, just as George Floyd finds scant consolation in the fact that his killers may never find deep peace. Wells, however, has a different focus, showing how delicious it is to act on dark impulses.

Griffin describes a “feeling of extraordinary elation” when he realizes that people can’t see him. Confiding his history to his college friend Kemp, he says he immediately burned down the house so that others wouldn’t discover his secrets:

“You fired the house!” exclaimed Kemp.

Fired the house. It was the only way to cover my trail—and no doubt it was insured. I slipped the bolts of the front door quietly and went out into the street. I was invisible, and I was only just beginning to realize the extraordinary advantage my invisibility gave me. My head was already teeming with plans of all the wild and wonderful things I had now impunity to do.

He uses the word “impunity” again further on:

Practically I thought I had impunity to do whatever I chose, everything—save to give away my secret. So I thought. Whatever I did, whatever the consequences might be, was nothing to me. I had merely to fling aside my garments and vanish. No person could hold me.

Griffin proceeds to engage in the same range of behavior that we are seeing from cops, from shoving to outright killing. At the beginning, his social infractions are minor:

My mood, I say, was one of exaltation. I felt as a seeing man might do, with padded feet and noiseless clothes, in a city of the blind. I experienced a wild impulse to jest, to startle people, to clap men on the back, fling people’s hats astray, and generally revel in my extraordinary advantage.

When Kent asks about “the common conventions of humanity,” Griffin replies that they are “all very well for common people.”

As Griffin’s madness grows, so do his dark ambitions. Thinking he has successfully enlisted Kemp, he plots ways to wield total power:

“And it is killing we must do, Kemp.”

“It is killing we must do,” repeated Kemp. “I’m listening to your plan, Griffin, but I’m not agreeing, mind. Why killing?”

“Not wanton killing, but a judicious slaying. The point is, they know there is an Invisible Man—as well as we know there is an Invisible Man. And that Invisible Man, Kemp, must now establish a Reign of Terror. Yes; no doubt it’s startling. But I mean it. A Reign of Terror. He must take some town like your Burdock and terrify and dominate it. He must issue his orders. He can do that in a thousand ways—scraps of paper thrust under doors would suffice. And all who disobey his orders he must kill, and kill all who would defend them.”

Note that he uses one of Trump’s favorite words here: “dominate.” He’s prepared to use violence if necessary.

A sadistic thrill comes with asserting your dominance over others. It’s not as fulfilling as serving humankind, as Socrates preaches and enlightened police know, but Griffin, racist cops, and authoritarians like Trump don’t care. They prefer the rush of acting with impunity.

The Invisible Man is transparent. America’s police forces, not so much.