Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Monday

A year ago today Donald Trump and his minions unleashed (to borrow from W.B. Yeats) “mere anarchy” upon America. I like Yeats’s use of the adjective because “mere” undermines their boasting. Trump and his ilk like to see themselves as big and bad, but in many ways January 6 was pathetic. Although many of those they attacked were scared and a number hurt, the Capitol invaders were no more than yahoos. To puff them up is to give them more substance than they warrant.

To be sure, they did drown “the ceremony of innocence”—the peaceful transfer of power that has been America’s pride and joy ever since its founding—and yes, January 6 undermined democracy. Anarchy puts ultimate power in the hands of bad actors. But it can be countered by people forcefully standing up for what is right. Grendel, an embodiment of the kind of anarchistic resentment that characterizes the MAGA movement, seems unbeatable until someone with firm resolve fights back. Then he retreats whimpering to his cave.

Unfortunately, anarchy prevails if people surrender in advance or if they make excuses for it, which is what the GOP has been doing. While some Republicans are filled with passionate intensity—including those who egged on the coup attempt—many more “lack all conviction.” They recognize Trump as a threat to the nation but prize their electoral prospects more. They remind me of a character in the Kate Atkinson detective novel Big Sky, which I’ve just finished reading.

Andy Bragg is helping to run a human trafficking ring, but his complicity is complicated by a Catholic conscience. How does he reconcile the two? The way many Republicans have managed to rationalize January 6. Here is Bragg delivering two women to the organization:

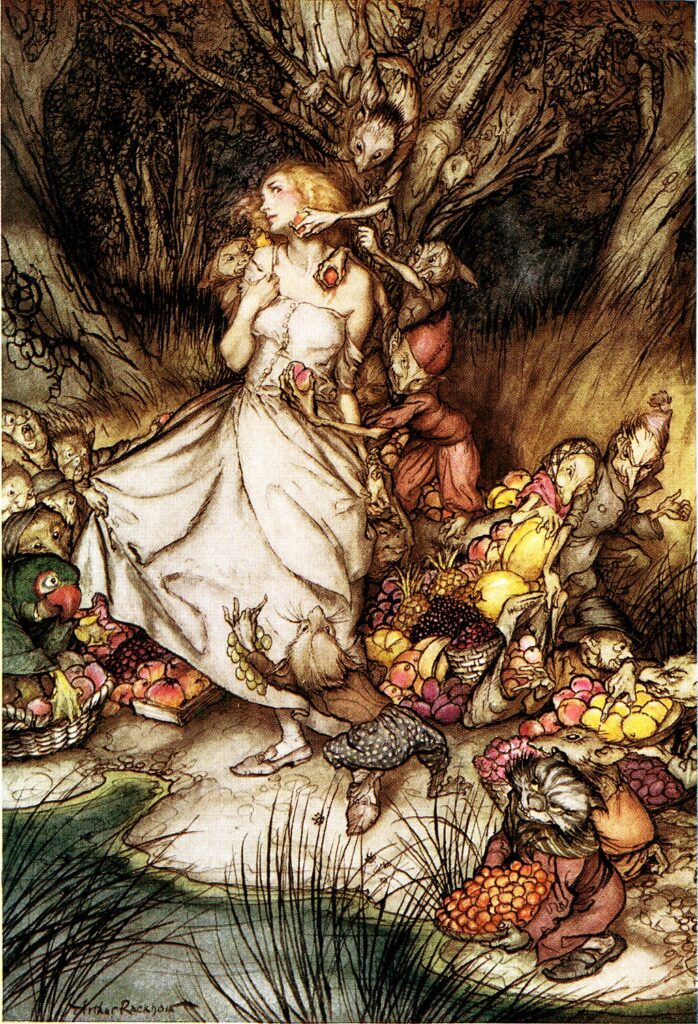

“It’s better inside,” Andy said. “You’ll see. Come on, now, out of the car.” He was a shepherd with two reluctant sheep. Lambs, really. To the slaughter. His conscience sprang up again and he hit it back down. It was like playing Whack-A-Mole.”

Each time a qualm about Trump’s coup attempt springs up, the GOP finds ways to whack it down. The rioters, they tell themselves, were actually Antifa activists or they were egged on by the FBI or they were just harmless tourists (although many were carrying weapons) or it wasn’t a big deal because nobody died (although some did) or it wasn’t a real coup attempt since it didn’t succeed or there was election fraud somewhere so it was okay or…or…or…

Liberals hope that conservatives can’t play Whack-a-Mole indefinitely. Indeed, Andy buckles in the end, doing something decent after he has been shot. But they may be overly optimistic on this score. After all, there were Germans who found ways to live with the concentration camps for years, facing up to reality only following military defeat. I use this example because my father witnessed it in action: one of his jobs as a member of the armed forces at the end of World War II was to take Germans through Dachau to show them what their government had done. Nothing made him angrier (I’ve read his letters home at the time) than their refusal to take responsibility.

In other words, people have amazingly accommodating moral compasses when self-interest is involved. As cynic Ambrose Bierce defines “moral” in his Devil’s Dictionary, “adj; conforming to a local and mutable standard of right. Having the quality of general expediency.” Or as Oscar Wilde put it, “Morality is simply the attitude we adopt towards people we personally dislike.”

Some are predicting that Trump, after pardoning the Capitol invaders (which he promises to do “on day one”), will attempt to turn January 6 into a national holiday, just as he’s attempting to turn insurrectionist Ashley Babbitt into a martyr. In the post I wrote on the first January 6 anniversary, I wondered if Trump could achieve with his coup attempt what the banana plantation owners do with the massacre of 3000 workers in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude:

The official version, repeated a thousand times and mangled out all over the country by every means of communication the government found at hand, was finally accepted: there were no dead, the satisfied workers had gone back to their families, and the banana company was suspending all activity until the rains stopped. Martial law continued with an eye to the necessity of taking emergency measures for the public disaster of the endless downpour, but the troops were confined to quarters. During the day the soldiers walked through the torrents in the streets with their pant legs rolled up, playing with boats with the children. At night, after taps, they knocked doors down with their rifle butts, hauled suspects out of their beds, and took them off on trips from which there was no return. The search for and extermination of the hoodlums, murders, arsonists, and rebels of Decree No 4 was still going on, but the military denied it even to the relatives of the victims who crowded the commandants’ offices in search of news. “You must have been dreaming,” the officers insisted. Nothing has happened in Macondo, nothing has ever happened, and nothing ever will happen. This is a happy town.” In that way they were finally able to wipe out the union leaders.

As far as the GOP is concerned, Trump’s electoral victory means that January 6 never happened. Their inner moles have given up.

Further thought: A recent article in Atlantic notes another form of erasure that today’s governments have at their disposal. “The Internet Is Worse Than a Brainwashing Machine,” observes the headline, with the follow-up, “A rationale is always a scroll or a click away.” Self-justifying whack-a-mole, in other words, has never been easier.