Tuesday

I recently finished reading Wilkie Collins’s Woman in White, which led me to take special notice of a former GOP strategist’s advice to Democrats. “Democrats play to win an argument; Republicans play to win an election,” contends Rick Wilson, author of the just released Running to Beat the Devil: How to Save America from Trump—and Democrats from Themselves. Seeing the election through Collins characters, the Democrats are Walter Hartright, the Republicans Count Fosco.

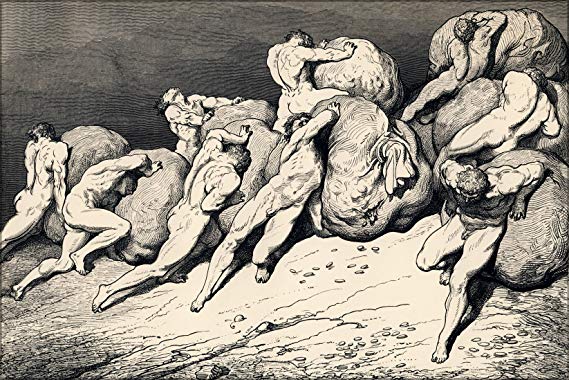

In order to gets his hands on a large inheritance, the devious Italian works with Lady Laura Glyde’s husband to have her stripped of her identity and imprisoned in an asylum. Hartright, who loves Laura, goes after the pair, which inadvertently leads to the death of the husband. Fosco, however, sends a warning through Laura’s half-sister Marian that his disregard for “the laws and conventions of society” will make him much tougher to defeat. Marian reports to Hartright,

“He spoke last of you. His eyes brightened and hardened, and his manner changed to what I remember it in past times—to that mixture of pitiless resolution and mountebank mockery which makes it so impossible to fathom him. ‘Warn Mr. Hartright!’ he said in his loftiest manner. ‘He has a man of brains to deal with, a man who snaps his big fingers at the laws and conventions of society, when he measures himself with ME. If my lamented friend had taken my advice, the business of the inquest would have been with the body of Mr. Hartright. But my lamented friend was obstinate. See! I mourn his loss—inwardly in my soul, outwardly on my hat. This trivial crape expresses sensibilities which I summon Mr. Hartright to respect….Let him be content with what he has got—with what I leave unmolested, for your sake, to him and to you. Say to him (with my compliments), if he stirs me, he has Fosco to deal with. In the English of the Popular Tongue, I inform him—Fosco sticks at nothing.’”

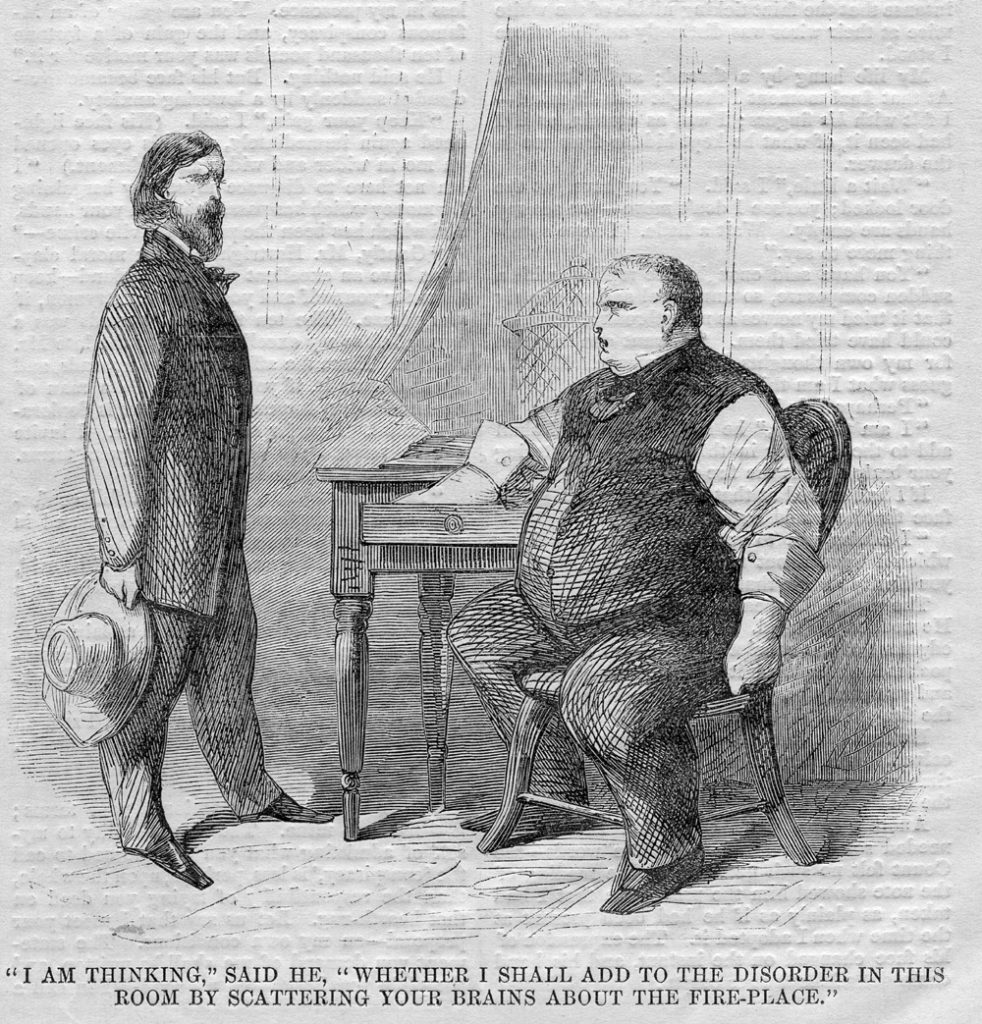

Later, when Hartright and Fosco come face to face, the Italian declares,

If the lives of twenty Mr. Hartrights were the stepping-stones to my safety, over all those stones I would go, sustained by my sublime indifference, self-balanced by my impenetrable calm. Respect me, if you love your own life!

What impedes Hartright, Fosco tells his foe, are his moral principles. “Your moral clap-traps have an excellent effect in England,” he says, channeling Machiavelli. “Keep them for yourself and your own countrymen, if you please.”

Hartright prevails in the end but his victory is not of his own doing. If Fosco weren’t assassinated by a secret society that somehow shows up at novel’s end, he would undoubtedly kill Hartright.

So the Democrats, according to Wilson, are essentially kept back by their moral clap-traps. They naively think they should play by the rules and operate according to principle. Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell consequently outmaneuver them time and again, from the Merritt Garland nomination to the Mueller investigation to the impeachment trial.

In my own moral universe, the soul is more important than political victory. But maybe Wilson would say that’s the problem.