Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

In this Christmas season, why are Republicans behaving like they are villains in a Charles Dickens novel? First, there was Iowa governor Kim Reynolds rejecting a federal summer program to feed underprivileged kids because she was worried that children would become too fat. Then Republican legislators in North Dakota rejected universal free school lunches on the grounds of cost, even while boosting their own meal allotment.

Their defensive rationales are what most remind me of Dickens since his comic satire shines most brilliantly when he’s having his villains defend their behavior. Check out how the trustees in Oliver Twist’s workhouse explain their food policies:

The members of this board were very sage, deep, philosophical men; and when they came to turn their attention to the workhouse, they found out at once, what ordinary folks would never have discovered—the poor people liked it! It was a regular place of public entertainment for the poorer classes; a tavern where there was nothing to pay; a public breakfast, dinner, tea, and supper all the year round; a brick and mortar elysium, where it was all play and no work. “Oho!” said the board, looking very knowing; “we are the fellows to set this to rights; we’ll stop it all, in no time.” So, they established the rule, that all poor people should have the alternative (for they would compel nobody, not they), of being starved by a gradual process in the house, or by a quick one out of it. With this view, they contracted with the waterworks to lay on an unlimited supply of water; and with a corn-factor to supply periodically small quantities of oatmeal; and issued three meals of thin gruel a day, with an onion twice a week, and half a roll of Sundays.

Compare this reasoning to that of Iowa governor Reynolds:

“Federal COVID-era cash benefit programs are not sustainable and don’t provide long-term solutions for the issues impacting children and families,” Reynolds said in a release. “An EBT card does nothing to promote nutrition at a time when childhood obesity has become an epidemic.”

In other words—if Iowa accepted federal funds, we’d have to keep feeding kids when the funds run out and furthermore kids don’t need the aid since they’re already eating badly.

And now check out a North Dakota legislator, courtesy of the Grand Forks Herald:

“Yes I can understand kids going hungry, but is that really the problem of the school district, is that the problem of the state of North Dakota? It’s really the problem of parents being negligent with their kids,” Senator Mike Wobbema said during the March 27 vote. Wobbema was one of the senators who voted in favor of boosting reimbursements for state workers like himself.

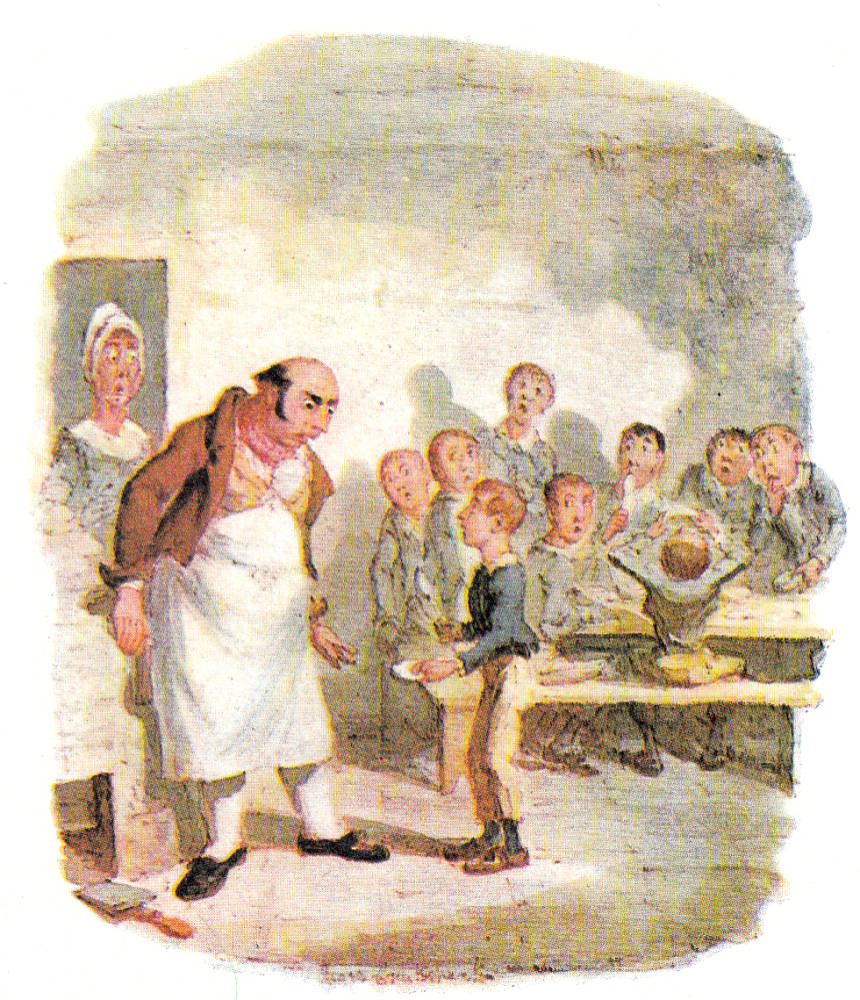

So it’s not the state’s problem. It’s the kids’ fault that their parents are negligent. One imagines Wobbema swelling up with indignation, just like Dickens’s workhouse beagle when Oliver asks for more gruel:

“Please, sir, I want some more.”The master was a fat, healthy man; but he turned very pale. He gazed in stupefied astonishment on the small rebel for some seconds, and then clung for support to the copper. The assistants were paralyzed with wonder; the boys with fear.

“What!” said the master at length, in a faint voice.

“Please, sir,” replied Oliver, “I want some more.”

The master aimed a blow at Oliver’s head with the ladle; pinioned him in his arm; and shrieked aloud for the beadle.

The board were sitting in solemn conclave, when Mr. Bumble rushed into the room in great excitement, and addressing the gentleman in the high chair, said,

“Mr. Limbkins, I beg your pardon, sir! Oliver Twist has asked for more!”

There was a general start. Horror was depicted on every countenance.

“For more!” said Mr. Limbkins. “Compose yourself, Bumble, and answer me distinctly. Do I understand that he asked for more, after he had eaten the supper allotted by the dietary?”“He did, sir,” replied Bumble.

“That boy will be hung,” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat. “I know that boy will be hung.”

So our Republicans, who are obsessed with cutting taxes on the wealthy, think they can find offsets by stiffing the poor. Dickens describes the potential savings:

For the first six months after Oliver Twist was removed, the system was in full operation. It was rather expensive at first, in consequence of the increase in the undertaker’s bill, and the necessity of taking in the clothes of all the paupers, which fluttered loosely on their wasted, shrunken forms, after a week or two’s gruel. But the number of workhouse inmates got thin as well as the paupers; and the board were in ecstasies.

Incidentally, I wondered what effect Dickens’s satire had on the poor laws of the time. I found the following from a google search:

While there is no direct link between Dickens’ work and the abolishment of the Poor Laws, his works sparked debate and changed the way people viewed what was going on in England at the time. Dickens’ vivid stories that captured the attention of the country gave faces and names to the tragedy that was the Poor Laws and showed a view into the lives of the poor. As people grew attached to Oliver and felt for his situation, many began to change their views on how the poor should be treated and the current modus operandi of ‘helping’ them.

One wonders whether even Dickens could shame our own legislators.