Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday – May Day

As today is May Day, I share some literary instances of mayday dancing. Such dancing, when connected with a maypole (so my internet research informs me), “is believed to have started in Roman Britain around 2,000 years ago, when soldiers celebrated the arrival of spring by dancing around decorated trees thanking their goddess Flora.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne features maypole dancing in “The Maypole of Merry Mount,” although in his case the tradition has lost its seasonal significance as the decadent revelers dance around the maypole throughout the year. It has degenerated into no more than an excuse to party.

This is not the case with Thomas Hardy, who uses the holiday to connect his rural characters with ancient Cerelean festivals—which is to say, rituals connected with fertility deities. In Tess of the d’Urbervilles, the dancers are all women:

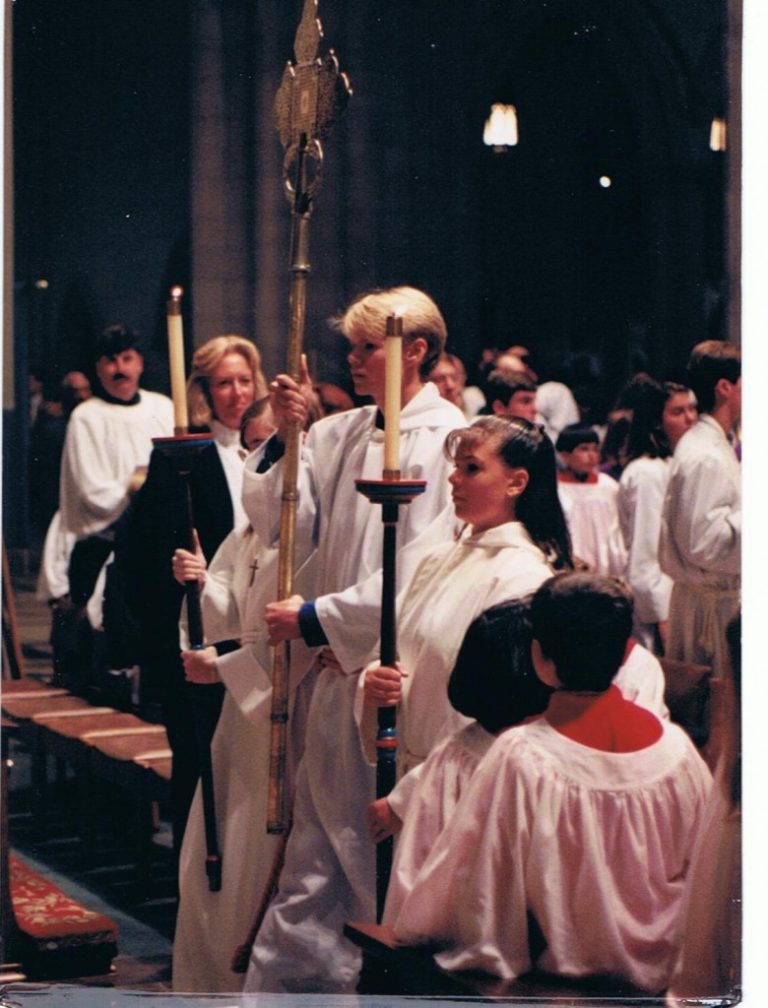

The banded ones were all dressed in white gowns a gay survival from Old-Style days, when cheerfulness and Maytime were synonyms days before the habit of taking long views had reduced emotions to a monotonous average. Their first exhibition of themselves was in a processional march of two and two round the parish.

In addition to the white frocks, Hardy tells us the dancers carry willow wands, images of fertility:

[E]very woman and girl carried in her right hand a peeled willow-wand, and in her left a bunch of white flowers. The peeling of the former, and the selection of the latter, had been an operation of personal care.

In Return of the Native, men join the festivities:

A whole village-full of sensuous emotion, scattered abroad all the year long, surged here in a focus for an hour. The forty hearts of those waving couples were beating as they had not done since, twelve months before, they had come together in similar jollity. For the time paganism was revived in their hearts, the pride of life was all in all, and they adored none other than themselves.

Hardy describes the phallic maypole in detail:

The pole lay with one end supported on a trestle, and women were engaged in wreathing it from the top downwards with wild flowers. The instincts of merry England lingered on here with exceptional vitality, and the symbolic customs which tradition has attached to each season of the year were yet a reality on Egdon. Indeed, the impulses of all such outlandish hamlets are pagan still—in these spots homage to nature, self-adoration, frantic gaieties, fragments of Teutonic rites to divinities whose names are forgotten, seem in some way or other to have survived mediæval doctrine.

The townsfolk witness the result of the May Day festivities the following morning:

[T]here stood the Maypole in the middle of the green, its top cutting into the sky. It had sprung up in the night, or rather early morning, like Jack’s beanstalk. She opened the casement to get a better view of the garlands and posies that adorned it. The sweet perfume of the flowers had already spread into the surrounding air, which, being free from every taint, conducted to her lips a full measure of the fragrance received from the spire of blossom in its midst. At the top of the pole were crossed hoops decked with small flowers; beneath these came a milk-white zone of Maybloom; then a zone of bluebells, then of cowslips, then of lilacs, then of ragged-robins, daffodils, and so on, till the lowest stage was reached. Thomasin noticed all these, and was delighted that the May revel was to be so near.

The purpose of the holiday is to connect with your natural roots. As you can’t do so if you fail to give yourself over fully to the earth’s natural forces, step outside and give it a whirl.