Tuesday

In yesterday’s post I observed that pandemic literature changed with the scientific revolution, which challenged religious ways of processing pandemics. It’s interesting, then, to see two contrary ways that pandemic novels view scientists. In a work like Michael Crichton’s Andromeda Strain (1969), scientists are the heroes, courageously attempting to prevent a deadly virus from escaping a laboratory and infecting the world. In works like Stephen King’s The Stand and Margaret Atwood’s Oryk and Crake, on the other hand, scientists take down the world’s population.

We see both suspicion and applause at work in today’s crisis. Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is demonized by some on the right and regarded as a national treasure by pretty much everyone else. It turns out that such ambivalence is at the heart of science fiction.

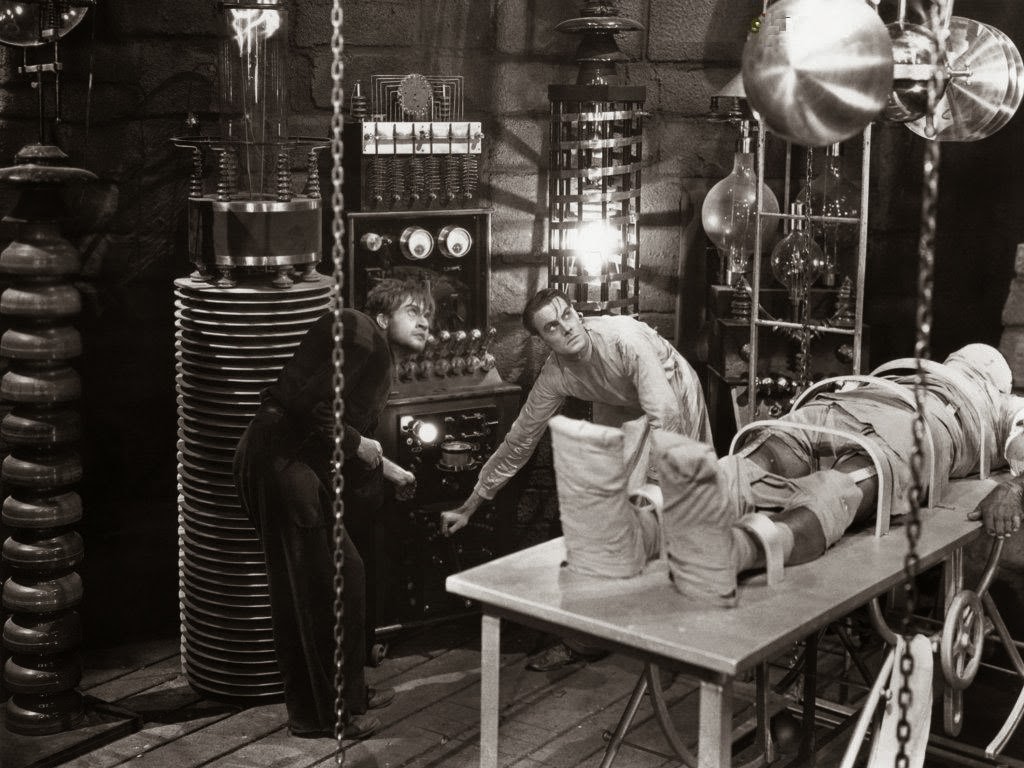

The ultimate example is the work that can be said to have launched the genre: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1823). The protagonist, while brilliant and inspiring, believes it is permissible to play God. Disaster ensues.

I mention as an aside that Shelley would go on to the write a novel about a killer pandemic, The Last Man (1826), in which everyone dies of a world-wide plague except for one man, who becomes a wanderer. This particular work may have set the stage for such novels as Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague (1915) and George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides (1949), in which individuals try to start the world anew. (Thanks to Vanderbilt librarian Valerie Hotchkiss for putting me on to these.) More recently, there’s Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven (2014), which I have written on here and here.

For all our fear of scientists losing their ethical bearings, we rely on them when a pandemic breaks out. Or, for that matter, when we find ourselves in a hospital ICU. For all of Donald Trump’s resentment at health experts telling him what to do—a resentment that led him to cut funding for the National Institute for Health, the Center for Disease Control, and groups researching global pandemics—he also dreams of a miracle medicine that will make Covid-19 go away. Who does he think comes up with such cures?

We get at the source of public suspicion in The Stand and Oryk and Crake. There we see science weaponized and, as in Frankenstein, the scientific breakthrough rebounding upon the inventor. In The Stand, a biological weapons lab has created a killer strain of the flu, which then escapes its containment. A worker at the facility, rather than selflessly sacrificing his life, panics and flees, thereby taking down the whole world. In King’s vision of humanity, evil impulses prompt us to devise such weapons in the first place.

Atwood’s vision is more complex. Thanks to the growing power of corporations, along with their bought politicians who strip away all regulations, gene technology is running amok. Exotic new animals are engineered, including pigs with internal organs available for human transplant and sheep with fleece that can be used for human hair. There are also wolfogs—guard dogs that will rip your throat out—and liobams, engineered by a fundamentalist sect that dreams of the day when the lion will lie down with the lamb.

In this world, pharmaceutical companies operate in a laissez-faire manner, sometimes unleashing viruses for which only they have the cure. Crake, a genius genetic engineer, is so disgusted by developments that he deliberately releases an illness, contained in an irresistible pleasure drug, that wipes out practically the entire human race. He also engineers an environmentally-sensitive human species to take our place.

Not all humans die, however, and, like Noah’s flood, this “waterless flood” doesn’t eradicate human evil. Several are back to their old evil ways by the trilogy’s end. So much for technological fixes.

Suspicion of science gone awry lies behind the anti-Vaxxer movement and, for that matter, attacks on Dr. Fauci. So that they can behave ethically and and communicate effectively, we need our scientists taking literature, philosophy, history and religion courses. The various Faust/Faustus stories show us only too clearly what happens when they make diabolic bargains and focus solely on the power unleashed by knowledge.

To that end, every scientist should read Frankenstein. The best science fiction has always worked as a “what-if” thought exercise, melding a profound understanding of human beings with the latest scientific and technological developments. Even when the science becomes outdated, as it has with Shelley’s work, the warnings are as prescient as ever.