Wednesday

I’m currently chairing Sewanee’s Friends of the Library committee, an organization committed to raising money for library projects and arranging a series of lectures and presentations. (I have given two card-playing presentations for the series, one on Speculation as it is played in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park and the other on Ombre from Alexander Pope’s Rape of the Lock.) We recently gave a framed and beautifully lettered copy of the following poem to two members who are rotating off the committee.

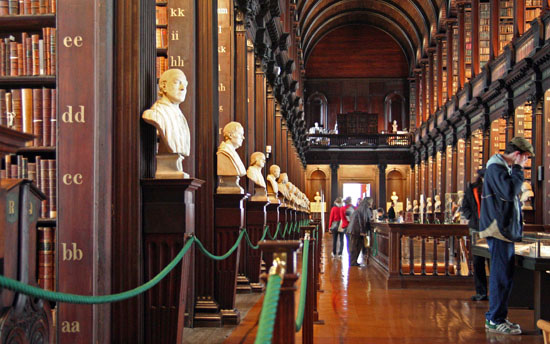

Written by Paul Hamilton Engle, once Iowa’s poet laureate, “Library” reminds us how powerful books can be, which is one reason public and school libraries are under assault by the MAGA at the moment. I love how Engle moves between seeing books as social dynamite and books as a comfort in terrible times. Of course, Engle is talking about all books, not just literature, but his observations apply to poems, plays and stories as well:

Library

(written on the 50th Anniversary Reunion of the Coe College Class of 1931)

Fire burns the trembling hand.

Cold freezes the fire fingers.

Rock breaks the unbending bone.

But books can grasp you by the throat and kill.

Go to a library, listen. You can hear

The books inside their bindings breathe aloud.

Hear reckless phrases howling from their type,

Hear jokes tickling you ear like a fine feather,

Hear screams of rage, delight, and agony.

Some books have brutal teeth that snap and bite,

Collared like dogs we lead them on a tight leash.

Passions of men and women cry

Out of silence from that printed page.

Some books, soft as a hand, caress your hand.

Beware the library, its books are sticks

Of dangerous dynamite that men have dropped.

When they explode, governments disappear.

Some covers hold ideas like live steam–

Open them, they shatter your live face.

The mind is a gun shooting at history.

than a rocket’s fuel–

The sky’s the limit in a fury of fire.

Libraries are alive, walls tremble, books

bounce on their shelves. In terrible times

Enter, your life comforted by their lives.

To demonstrate my agreement, here’s a passage from my book Better Living through Literature, released yesterday:

[W]hen English teachers play it safe, they risk underplaying literature’s fierce urgency and its ability to speak directly to our life struggles. Taming literature down to a boring irrelevancy leaves its potential untapped. Students go unchallenged in ways that could lead to real and exhilarating growth.

This is why it’s useful to acquaint ourselves with stories of literature stepping up to the plate during tough times, often in the most unexpected of ways. Who could have predicted a Somali political prisoner falling in love with Anna Karenina or a kidnapped Pakistani girl turning to Little Women?Who could foresee Iranian women, banished from universities by fundamentalist mullahs, recognizing themselves in the character of Vladimir Nabokov’s Dolores Haze? (In Reading Lolita in Tehran, Azar Nafisi reports that her students related to how Dolores is trapped in an older man’s fantasies.)

And then there are the South African freedom fighters who, when imprisoned by the apartheid regime, found purchase in the words of various Shakespeare characters. Nelson Mandela responded to Julius Caesar’s “Cowards die many times before their deaths; / The valiant never taste of death but once”; his confidant Walter Sisulu saw himself in Shylock: “Still have I borne it with a patient shrug / For sufferance is the badge of all our tribe”; and future Parliament member Billy Nair saw a kindred soul in Caliban: “This island’s mine, by Sycorax my mother / Which thou tak’st from me.” Why limit literature instruction to rhyme and meter when you could be preparing your students for life?

When I come across stories of people attacking and sometimes banning works of literature, I think of a scene from the Lawrence Kasdan film Grand Canyon (1991). Danny Glover, in the role of auto mechanic, is confronted by a gun-wielding gang leader while attempting to help stranded motorist Kevin Kline. Asked by the man whether he respects him or not, Glover replies, “You ain’t got the gun, we ain’t having this conversation.” These contentious conversations about literature are happening because literature wields the power of a loaded gun.

Literature is like Aslan as he is described by Mr. Beaver in C.S. Lewis’s Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. When Lucy asks whether he is safe, Mr. Beaver replies,

Safe? Who said anything about safe? ‘Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.

Elsewhere Mr. Beaver says, “He’s wild, you know. Not like a tame lion.”

Poems, plays, stories. Not safe. Not tame. But good.