Spiritual Sunday

Henry Vaughan, the mystical 17th century Welsh Anglican poet, was an early forerunner of Romanticism, a poet who was a major influence on William Wordsworth. Today I have a spring poem in which Vaughan riffs off of a beautiful passage from Song of Solomon: “Awake, north wind, and come, south wind! Blow on my garden, that its fragrance may spread everywhere. Let my beloved come into his garden and taste its choice fruits.”

The poem, as the title indicates, is about a man seeking spiritual “regeneration.” Although his spring walk is “primrose and hung with shade,” the poet is feeling shackled by sin so that he feels it to be “frost within”:

[S]urly winds

Blasted my infant buds, and sin

Like clouds eclipsed my mind.

Spring, no matter how beautiful, is not going to pull him out of his funk. Therefore, he turns to prayer, which reveals to him an eternal spring. (“But thy eternal summer shall not fade,” Shakespeare writes to his lover in Sonnet 18.) This new spring features a burbling fountain within which varicolored stones dance “quick as light.” This heavenly spring seems to well up within the poet as well (an internal spring) and all seems well.

He’s not home free yet, however. In the fountain he also hears “the music of her tears” and the heaviest stone, which is “nailed to the center,” recalls the crucifixion.

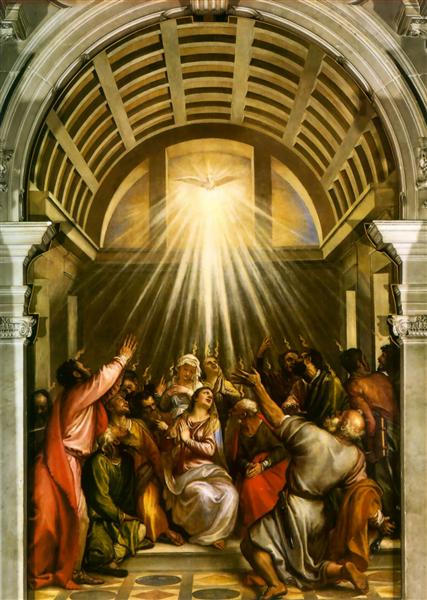

Yet this spring has much more promise than his first spring, for the image then shifts to a bank of flowers, suggesting the resurrection. This is turn is followed by a rushing wind, which points towards Pentecost and the descent of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:2: “And suddenly there came from heaven a sound as of the rushing of a mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting.) This breath of God blows where God pleases.

Vaughan, who has been feeling blasted, asks to feel God’s breath as the disciples felt it. After that, he doesn’t care what happens to him: “‘Lord,’ then said I, ‘on me one breath,/ And let me die before my death!’”

Regeneration

By Henry Vaughan

A ward, and still in bonds, one day

I stole abroad;

It was high spring, and all the way

Primrosed and hung with shade;

Yet was it frost within,

And surly winds

Blasted my infant buds, and sin

Like clouds eclipsed my mind.

Stormed thus, I straight perceived my spring

Mere stage and show,

My walk a monstrous, mountained thing,

Roughcast with rocks and snow;

And as a pilgrim’s eye,

Far from relief,

Measures the melancholy sky,

Then drops and rains for grief,

So sighed I upwards still; at last

’Twixt steps and falls

I reached the pinnacle, where placed

I found a pair of scales;

I took them up and laid

In th’ one, late pains;

The other smoke and pleasures weighed,

But proved the heavier grains.With that some cried, “Away!” Straight I

Obeyed, and led

Full east, a fair, fresh field could spy;

Some called it Jacob’s bed,

A virgin soil which no

Rude feet ere trod,

Where, since he stepped there, only go

Prophets and friends of God.Here I reposed; but scarce well set,

A grove descried

Of stately height, whose branches met

And mixed on every side;

I entered, and once in,

Amazed to see ’t,

Found all was changed, and a new spring

Did all my senses greet.

The unthrift sun shot vital gold,

A thousand pieces,

And heaven its azure did unfold,

Checkered with snowy fleeces;

The air was all in spice,

And every bush

A garland wore; thus fed my eyes,

But all the ear lay hush.

Only a little fountain lent

Some use for ears,

And on the dumb shades language spent

The music of her tears;

I drew her near, and found

The cistern full

Of divers stones, some bright and round,

Others ill-shaped and dull.The first, pray mark, as quick as light

Danced through the flood,

But the last, more heavy than the night,

Nailed to the center stood;

I wondered much, but tired

At last with thought,

My restless eye that still desired

As strange an object brought.It was a bank of flowers, where I descried

Though ’twas midday,

Some fast asleep, others broad-eyed

And taking in the ray;

Here, musing long, I heard

A rushing wind

Which still increased, but whence it stirred

No where I could not find.

I turned me round, and to each shade

Dispatched an eye

To see if any leaf had made

Least motion or reply,

But while I listening sought

My mind to ease

By knowing where ’twas, or where not,

It whispered, “Where I please.”“Lord,” then said I, “on me one breath,

And let me die before my death!”

Think of the Holy Spirit entering like a gentle spring breeze.