Spiritual Sunday – Father’s Day

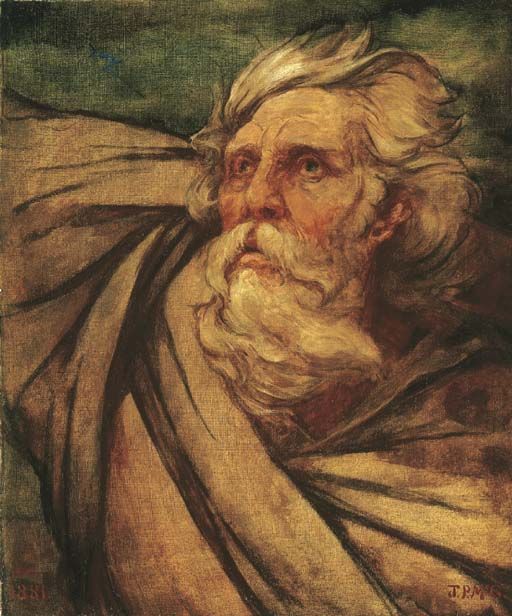

African American poet Thylias Moss has this wonderful poem about how God improved after he had, and became, a son. Moss would agree with those theologians who see the God as a character who evolves in the course of the Bible.

Another way of putting this is that humankind’s understanding of God has evolved over time, with the Bible reflecting those changes. God may not have changed, but we have.

In any event, Moss has written a compelling poem, capturing us in all our vulnerable humanity and our transcendent longing. I particularly like the moment when, by entering Mary’s womb, God becomes more feminine. And how, by going through the evolutionary stages (ontogeny recapitulating phylogeny, as the biologists put it), he chooses to come out human, with all that this entails.

A Man

How handsome he was, that man who did not court

the girls fawning all over him as if he’s already saved them,

it’s my leg, one said, raising her hem as she’d raised it

in dreams

he knew of, for everything reached him as prayer, my leg, Sir,

is not perfect although as he looked, it glistened and the blood

became more productive. He did not date, nor rendezvous

in tunnels and tents,

did not kiss except to heal, did not harass, malign

nor mutilate;

threw no stones

and he was a man; never forget that he was a man,

that being a man improved him. Before the mothering. He was

a solo act

ramming omnipotence down the throats of Ramses, Job, all

the sinning nobodies

of Sodom. He was feared before he was born a triplet

of flesh completing

the one vaporous, the other heavy and strict; now he’s

desirable, vulnerable;

in the mother he visited stages of: fig, fish, pig, chicken,

chimp before settling irrevocably

on a form more able to strive. This was a more significant

time in darkness,

gestation of forty weeks, than three days in a hillside morgue;

he learned maternal heartbeat

and circulation of her blood so well they became dependency,

and so he learned that some radiance is not his, hers

came in large part just from being Mary—how content she was

even before pregnancy,

betrothed, blushing to ripen the fields; content even before she

knew of angels,

and now, with this mound of baby, she was parent of a world

whose prospering

she encouraged, activity of fish, magma, sulfur, the earth

striving

just as she did.

He was a man

yet the usher of miracles, preaching

on a mountain

where reverberation gave him the power of five thousand

tongues, yet not

a big man, not athletic, ordinary looking except for that glow

and doves circling

him in the desert, doves that had been vultures earning their

transfiguration

by consuming decaying meat just as he ate all the sin; for that

flattery, he bid them dip their

feathers in his eye, drawing into them that sweet milk around

the iris.

He was a man

when he began to understand love,

erasing the lines between

Gentile, Jew, and invited any who wanted to come to his father’s

house for bottomless milk,

honey, ripe fruit, baskets of warm bread and eggs, wine,

live angels singing. Weary revelers

could lay their heads on his breast, he said, needing intimacy; he

thinks

as a man, therefore

he is a man

and good times, memories can be

adequate heaven. He knows the distance a man

is from his father, how likely it increases till the deathbed;

he knows

what a man knows

the now and here, and can be called by name,

and can be wounded, and must struggle, and must be proud

every now and then or could not continue, must be worth

something,

must be precious to himself and preferably to at least one other,

must be,

in these thousands of post-Neanderthal years, improving,

must have

more potential, becoming not only more like God, but more like

what God needs to become, so moves also,

so God moves also

because a man moves.