Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Wednesday

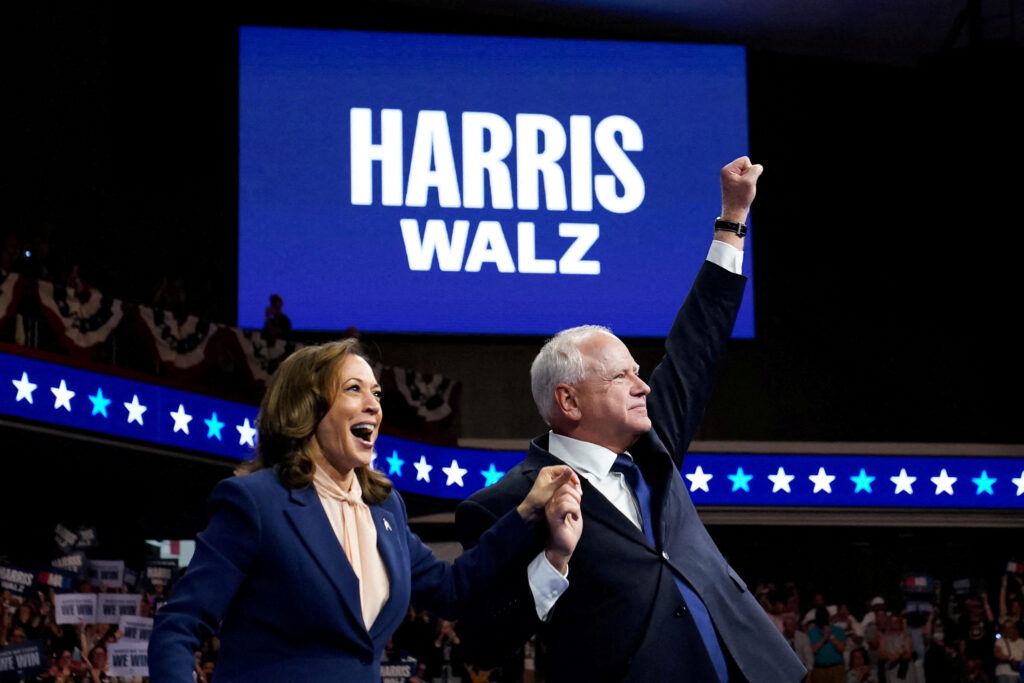

One of the loveliest aspects of the large Kamala Harris rallies is the periodic chants of “We love you, Joe.” They are testimony to the deep affection that Democrats have for the current president, including many who were pressuring him to step down. We are so unaccustomed in politics to seeing selflessness win out over ego—of people putting the welfare of the community over themselves—that it seemed miraculous when it happened. Joseph Robinette Biden deserves much of the credit for the Democrats’ smooth transition to Harris.

I’ve written about how the transition taps into the Fisher King archetype. But there’s another mythic narrative at work as well, one which J.K. Rowling uses in the conclusion of the Harry Potter series.

In The Deathly Hallows, Harry Potter gives up his life in order to defeat Voldemort. Having received a final message from a dying Snape, Harry realizes what he must do to defeat his archenemy. Voldemort has issued an ultimatum—if Harry does not meet him at a designated time in the Forbidden Forest, Voldemort will “punish every last man, woman , and child who has tried to conceal you from me”—and Harry realizes he must surrender to save them:

Lying with his face pressed into the dusty carpet of the office where he had once thought he was learning the secrets of ciry, Harry understood at last that he was not supposed to survive. His job was to walk calmly into Death’s welcoming arms.

There’s more at work here than merely offering himself up as a sacrificial lamb. In a complicated plot twist that confuses even Harry Potter fans, Harry carries within him a fragment of Voldemort’s soul. (I’ll have more to say about the political applicability of this symbolism.) Therefore, when Voldemort thinks he is killing Harry, he is actually killing his own soul. And because Harry is one of the remaining horcruxes that Voldemort uses to stay alive, the dark lord renders himself vulnerable to defeat at the very moment when he thinks he has vanquished his foe.

I suspect you can see where I’m going with this. By choosing selflessness over ego and by designating a dynamic woman of color as his successor, Biden unleashed a positive energy that is buoying the Democrats. While the dynamic Harris and her vice-presidential pick Tim Walz certainly bring their own energy, Biden created the narrative.

His selfless decision has utterly flummoxed Trump, who is flailing at the moment and may not recover. After all, according to his understanding of the universe, people do not willingly surrender power. What Dumbledore says to Harry in the limbo world to which he has gone after Voldemort “kills” him applies equally to the past president:

He was more afraid than you were that night, Harry. You had accepted, even embraced, the possibility of death, something Lord Voldemort has never been able to do. Your courage won. Your wand overpowered his.

During his time in this limbo world, Harry sees the fragment of the Voldemort soul that he has been carrying, the fragment that Voldemort blasted with his wand. Think of it as Trump’s own inner self:

[Harry] recoiled. He had spotted the thing that was making the noises. It had the form of a small, naked child, curled on the ground, its skin raw and rough, flayed-looking, and it lay shuddering under a seat where it had been left, unwanted, stuffed out of sight, struggling for breath.

This figure fits the image that psychologist Mary Trump gives of her uncle. Much about Trump can be explained by the emotional neglect he suffered when he was growing up, she writes:

When Donald was a young child, his mother, my grandmother, was very ill. For about a year, starting when Donald was two and a half, he didn’t have a primary caregiver because she was physically and emotionally unavailable to him. There was nobody there to do the essential parenting that children at that extremely crucial developmental period need. Toddlers need to be seen; they need to be soothed. He didn’t get any of that, not only because my grandmother wasn’t there for him, but because the person who replaced her, my grandfather, was a straight up textbook sociopath.

The result is the whimpering, thumping man who for four years was our president and who is striving to become so again. When Harry and Dumbledore look down at the figure, however, Dumbledore tells his protégé to look toward the future:

Do not pity the dead, Harry. Pity the living, and above all, those who live without love. By returning, you may ensure that fewer souls are maimed, fewer families are torn apart. If that seems to you a worthy goal, then we say good-bye for the present.

My parallel with Election 2024 breaks down a little here because, of course, it is not Biden who returns to battle Voldemort but a successor. Biden in this scenario is more Obi-Wan Kenobe giving himself up so that Luke Skywalker can triumph. So shift gears for a moment and think of Biden as Dumbledore and Harris as Harry. Imagine Harris squaring off in a final confrontation with the dark lord, the two circling with wands out.

At first glance, it appears that Harry doesn’t have a chance. After all, Voldemort is wielding the Elder Wand, which like Tolkien’s Ring of Power is the ultimate weapon. To obtain it, Voldemort has killed ruthlessly.

Harry, however, has access to a deeper magic. He has seen in Dumbledore what Harris has seen in Biden, that love of others is more powerful than authoritarian power trips. He informs Voldemort of this in their faceoff:

“I know things you don’t know, Tom Riddle (Voldemort’s human name). I know lots of important things that you don’t. Want to hear some, before you make another big mistake…”

“Is it love again?” said Voldemort, his snake’s face jeering. “Dumbledore’s favorite solution, love, which he claimed conquered death, although love did not stop him falling from the tower and breaking like an old wax work?”…

“Yes Dumbledore’s dead,” said Harry calmly, “but you didn’t have him killed. He chose his own manner of dying…”

That manner of dying, it so happens, ultimately leads to Harry becoming the master of the Elder Wand, just as Biden’s symbolic death led to the ascendency of a woman of African-Asian descent. When Voldemort tries to use the wand against him, therefore, the curse rebounds, killing Voldemort instead. The wand meanwhile finds its way into Harry’s hand.

Could it be that Biden’s determination to be president of all Americans—a vision that Harris shares—will win out over Trump’s attempt to demonize those who don’t look and think like him? As I write this, things are looking up.

The difference between how Voldemort sees the Elder Wand and how Dumbledore and Harry see it is also significant for our purposes. Trump, J.D. Vance, and the authors of Project 2025 regard the presidency as the Elder Wand, a means of imposing a Christian nationalist state on all Americans. They have even persuaded our rightwing Supreme Court to grant the president absolute immunity for all “official duties.”

Rather than use this power himself, however, Biden has proposed laws stripping the president of this power. Meanwhile Harry, although himself now possessor of the Elder Wand, gets rid of it at the end. He uses it once—to repair his old wand—and then gives it up. It’s worth noting that he dismisses total power with little more than a shrug:

“That wand’s more trouble than it’s worth,” said Harry “And quite honestly…I’ve had enough trouble for a lifetime.”

I promised you a further observation on the significance of Harry and Voldemort being intertwined so here it is. Biden is not without ego. To run as long and as hard for president as he did would be impossible without it. In other words, although not the narcissist that Trump is, he had that Trumpian element within him. Harry’s development throughout the series is in part an internal struggle with his Voldemort side. Or as Jung would describe it, his shadow side.

I imagine Biden taking Harry’s walk to the Forbidden Forest as he wrestled with whether or not to drop out of the race. Harry almost turns back, and it is only because of supportive voices from his past, including those of his father and mother, that he can continue on. Biden must have been bolstered by his own supportive voices in agreeing to what, at times, felt like a kind of death.

Again, accepting the death of the ego is so far beyond anything Trump could imagine that Biden’s move has left him utterly bewildered. Reality has shifted under his feet and he can’t adjust.

Further thought – As I was rereading the end of Deathly Hollows for this blog entry, I realized how much Rowling has borrowed from C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, with Voldemort as the White Witch and Harry as the Christ-figure Aslan. While Biden is no Christ, his self-sacrifice is very much in that spirit. As a devout Catholic, Biden would know the words from John, “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.”