Note: Comments can be sent to rrbates1951@gmail.com. Also, you may write me there if you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

Someone has just written to our local newspaper, the Sewanee Mountain Messenger, about the year’s first hummingbird sighting. This gives me an excuse to share a fun hummingbird poem, written by Beth Ann Fennelly (thanks to Jonathan Rebec for alerting me to it).

Though Fennelly is more focused on the last hummingbird rather than the first, she points to the entire seasonal cycle. We gasp when we see the first one, appearing as a stereotyped picture of happiness—“hands clasped, like a child actor instructed to show joy.” And then there are the midsummer swarms, when I’ve counted as many as ten hummingbirds at our feeders. A collection of hummingbirds is called a “charm” or a “hover” and sometimes a “troubling.” To me, however, they sometimes resemble a swarm of large mosquitoes.

What distinguishes the last hummingbird is that we never know that it’s the last. The poet observes that there’s “no telling, and no tell”: we think we have seen the last one and then there’s another one and so on until, finally, there really are no more.

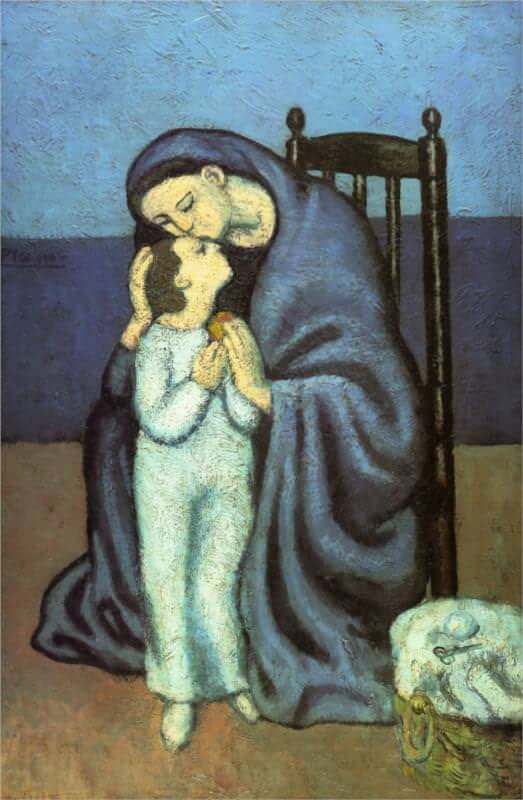

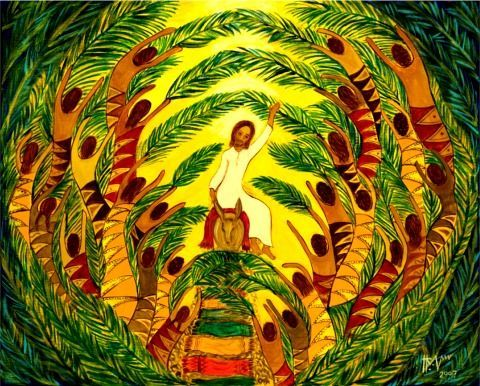

At this point in the poem, Fennelly shocks us with a dramatic and unexpected comparison: to menstruation! Just as the hummingbird appearances go through a cycle, so does a woman’s period. While the first is like the angel Gabriel appearing to Mary (with the poet, for good measure, throwing in an allusion to Judy Blume’s teen classic about periods, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret), the last is like “your last, perhaps, or next-to-last, your no-long-very-monthly monthly.”

And just as “your body’s eggy miracle” has been “unneeded now for years,” so the uncertainty surrounding hummingbird departures leads to sugar water being wasted. (“Why fill and dump and fill again the undrunk sugar water?” Fennelly asks. “Enough. Let’s progress to whatever season’s next.”)

And yet, one doesn’t want to progress without some “farewell ritual.” She imagines the last hummingbird, in its departure, dipping its wing, as pilots sometimes do to indicate a final farewell.

The Last Hummingbird of Summer

By Beth Ann Fennelly

reveals itself in retrospect. Unlike the first,

whose March arrival bade you gasp, hands clasped,

like a child actor instructed to show joy, when the last

departs for points south, there’s no telling,

and no tell. Well, so what? You know their cycle.

In August, they swarm the feeder, all swagger,

greedy tussle for sugar water. Suddenly,

September. Chill tickles your ankles. You reach

for long sleeves and you fret. They’ve left? Not yet.

Ear cocked for the symphony’s shrinking strings.

Then comes a day without a ruby flash. Next day,

they’re back. Next day, there’s one. Then none.

Or maybe one? From porches, pumpkins grin.

Your last had left, and left you uninformed.

Kinda? Sorta? Can I say it?—like menstrual blood,

again, between your legs. Your last, perhaps,

or next-to-last, your no-longer-very-monthly

monthly. So unlike your first crimson, at twelve,

its “Yes-You-Are-There-God” annunciation.

Well, so what? You know the cycle. Your body’s

eggy miracle, unneeded now for years.

And you hate waste. Why fill and dump

and fill again the undrunk sugar water?

Enough. Let’s progress to whatever season’s next.

But still, a farewell ritual wouldn’t be amiss.

The last hummingbird of summer, zinging

from the feeder—to others, a smooth departure—

to you, alone, unmistakably, dipping its wing.

Whenever I read a poem like this, I think of how poet Lucille Clifton gave women permission to write about their bodies, starting with “homage to my hips” (early 1970s) and eventually moving on to lyrics like “poem in praise of menstruation” and “wishes for sons.” I love her own farewell poem “to my last period”:

well, girl, goodbye,

after thirty-eight years.

thirty-eight years and you

never arrived

splendid in your red dress

without trouble for me

somewhere, somehow.

now it is done,

and i feel just like the grandmothers who,

after the hussy has gone,

sit holding her photograph

and sighing, wasn’t she

beautiful? wasn’t she beautiful?

So which should one be more sentimental about, the last hummingbird or one’s last period? Not being a woman, I’ll let others answer that one.