Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

Last week President Joe Biden officially designated almost a million acres of land north and south of the Grand Canyon as the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni [Our Ancestral Footprints] National Monument. In doing so, he closed the land off to new uranium mining, which put me in mind of Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony. Uranium plays a significant thematic role in the novel by the Laguna Pueblo author, and the move to ban further mining is in line with Silko’s desire to push back against what she calls “the witchery.”

First, a note about uranium mining in the area. According to science reporter Justine Calma of The Verge (blogger Heather Cox Richardson alerted me to her article), past uranium mining left 500 abandoned mines on Navajo Nation land, and pollution from those mines has been linked to life-threatening illnesses among children there. Nevertheless and predictably, Republicans are objecting to prohibiting further uranium mining. (The present uranium mines are grandfathered in.)

Richardson notes that the move is part of a larger promise Biden made about protecting 30% of all the nation’s lands and waters by 2030. To date, Richardson reports, the Biden administration has protected

9 million acres in Alaska, 225,000 acres in Minnesota, 50,000 acres in Colorado, 500,000 acres in Nevada, and 6,600 acres in Texas. It has restored protections for three national monuments the previous administration had gutted: Grand Staircase–Escalante and Bears Ears in Utah and Northeast Canyons and Seamounts off the New England coast. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland is working on creating a maritime sanctuary by protecting 770,000 square miles in the Pacific Ocean southwest of Hawaii.

And then there’s this:

The administration is also, [Biden] said, honoring his commitment “to prioritize respect for the Tribal sovereignty and self-determination, to honor the solemn promises the United States made to Tribal nations to fulfill federal trust and treaty obligations.” The protected land is home to 3,000 cliff houses, cave paintings, and other Indigenous cultural sites. Biden explained that the land being protected and the land already protected as the Grand Canyon National Monument had been Indigenous homelands.

Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, meanwhile, has included funding to clean up such industrial pollution in the region, including the abandoned oil wells that leak toxic gases into the air and hazardous chemicals into the water.

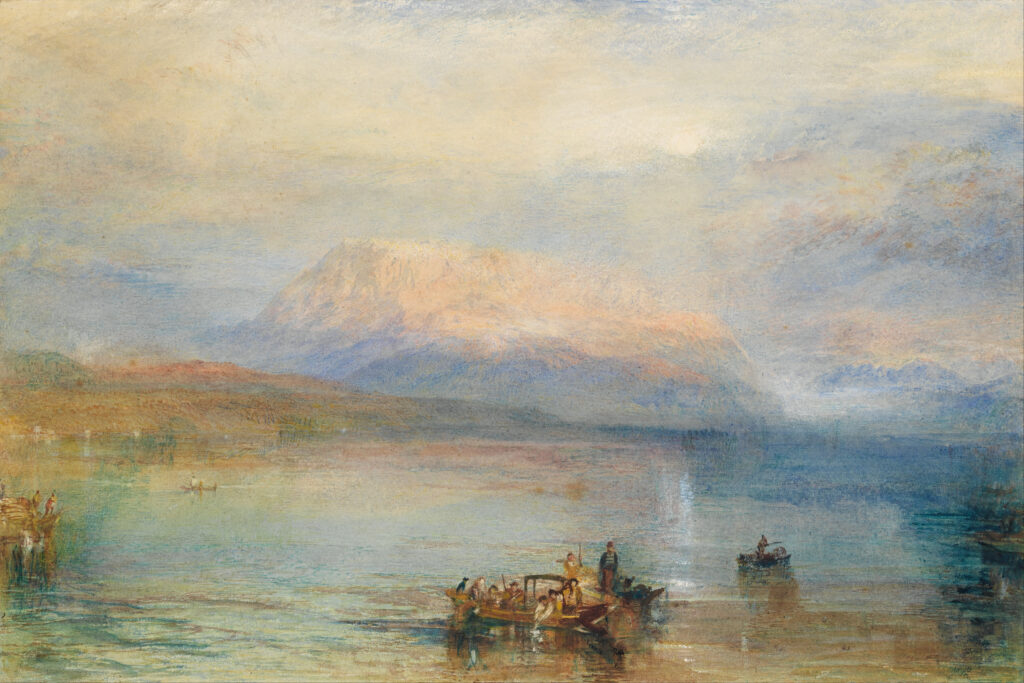

Ceremony is a novel about an Indian war veteran who returns from World War II, having survived the Bataan Death march in which thousands of Filipino and American prisoners died. Tayo is suffering from PTSD but that’s not his only problem. In addition to survivor guilt and various family and tribal issues, he returns to a land in which White America is destroying the land and undermining the Indians’ connection with it. At one point, the destruction is articulated as a story poem. About the Whites, Silko writes,

Then they grow away from the earth

then they grow away from the sun

then they grow away from the plants and animals.

They see no life

When they look

they see only objects.

The world is a dead thing for them

the trees and rivers are not alive

the mountains and stones are not alive

The deer and bear are objects

They see no life

They fear

They fear the world.

They destroy what they fear.

They fear themselves.

This is not the worst of it, however. The culmination of this destruction is nuclear annihilation of everyone:

They will take this world from ocean to ocean

they will turn on each other

they will destroy each other

Up here

in these hills

they will find the rocks,

rocks with veins of green and yellow and black.

They will lay the final pattern with these rocks

they will lay it across the world

and explode everything

Seeking to find shelter at an abandoned uranium mine as former Indian companions seek to kill him (it’s not only Whites who are murderous), Tayo comes across some of these rocks:

He knelt and found an ore rock. The gray stone was streaked with powdery yellow uranium, bright and alive as pollen; veins of sooty black formed lines with the yellow, making mountain ranges and river across the stone. But they had taken these beautiful rocks from deep within earth and they had laid them in a monstrous design, realizing destruction on a scale only they [the witches] could have dreamed.

Tayo’s grandmother has witnessed the explosion of Trinity, which occurred three hundred miles to the southwest. Uranium mining on Indian land, which eventually leads to the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, gives Tayo a way of connecting the local with the global. Suddenly he sees all humankind united against a common enemy:

[T]he lines of cultures and worlds were drawn in flat dark lines on fine light sand, converging in the middle of witchery’s final ceremonial sand painting. From that time on, human beings were one clan again, united by the fate the destroyers planned for all of them, for all living things; united by a circle of death that devoured people in cities twelve thousand miles away, victims who had never known these mesas, who had never seen the delicate colors of the rocks which boiled up their slaughter.

The final showdown occurs at the uranium mine. Deprived of their victim, Tayo’s former companions turn on each other in a bloody ritual. Tayo resists yielding to his own anger and, in so doing, emerges with a sense of the healing the world needs. Silko writes,

Big clouds covered the moon, but he could still see the stars. He had arrived at a convergence of patterns; he could see them clearly now. The stars had always been with them, existing beyond memory, and they were all held together there. The stars had always been with them, existing beyond memory, and they were all held together there. Under these same stars the people had come down from White House in the north. They had seen mountains shifts and rivers change course and even disappear, back into the earth; but always there were these stars.

So the world will keep going although Silko then adds a cautionary note:

The only thing is: it has never been easy.

Honoring tribal lands and addressing the pollution left over from uranium mines and oil wells is one way of pushing back against the witchery. So is taking strides against global warming and climate change. As the world teeters between darkness and light, we must start by tapping into our inner light and then doing the best we can.

Silko shows us the way. To his credit, President Biden is doing what he can to make sure we take the necessary steps.