Wednesday

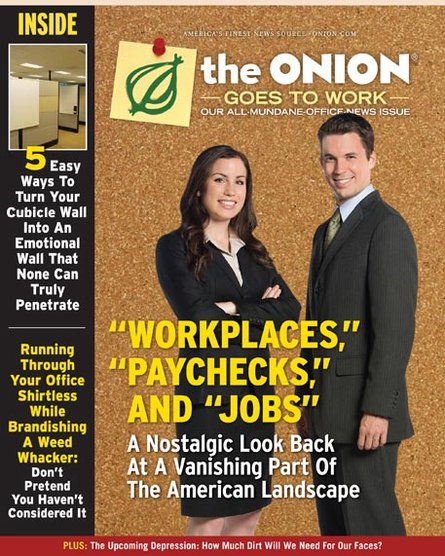

It’s not often that The Onion, perhaps America’s foremost publication for comic parody, gets serious, but it got serious recently—or at least semi-serious—when it supported a man who had been jailed for, well, parody.

According to Institute for Justice, here’s what happened. Anthony Novak, long-time resident of Parma Ohio, created a mock Facebook page imitating that Facebook page of the Parma police department. After receiving 11 complaints, the police arrested Novak, even though it didn’t take much to recognize his creation as parody (starting with its satirical slogan, “We no crime”). Among its items were the announcement “of an ‘official stay inside and catch up with family day’ to ‘reduce future crimes’ during which anyone caught outside would be arrested.”

Unamused, the Parma Police Department

obtained a warrant for his arrest, searched his apartment, seized his electronics, and charged him with a felony under an Ohio law that criminalizes using a computer to “disrupt” “police operations.” Anthony had to spend four days in jail before making bail. He was prosecuted, but after a full criminal trial, a jury found him not guilty.

In response, Anthony filed a civil-rights lawsuit against the department, only to see the 6th U.S. U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals grant the officers qualified immunity and dismiss the case. He has appealed the case to the Supreme Court, which is where the Onion’s supportive brief enters the scene.

While solidly argued and filled with the relevant precedents, the Onion’s brief is unusual in that it performs parody to make its case. For instance, here’s how it describes itself:

The Onion is the world’s leading news publication, offering highly acclaimed, universally revered coverage of breaking national, international, and local news events. Rising from its humble beginnings as a print newspaper in 1756, The Onion now enjoys a daily readership of 4.3 trillion and has grown into the single most powerful and influential organization in human history.

In addition to maintaining a towering standard of excellence to which the rest of the industry aspires, The Onion supports more than 350,000 full- and parttime journalism jobs in its numerous news bureaus and manual labor camps stationed around the world…

And:

The Onion’s journalists have garnered a sterling reputation for accurately forecasting future events. One such coup was The Onion’s scoop revealing that a former president kept nuclear secrets strewn around his beach home’s basement three years before it even happened.

The brief goes on to explain The Onion’s reasons for supporting Novak’s lawsuit:

Americans can be put in jail for poking fun at the government? This was a surprise to America’s Finest News Source and an uncomfortable learning experience for its editorial team. Indeed, “Ohio Police Officers Arrest, Prosecute Man Who Made Fun of Them on Facebook” might sound like a headline ripped from the front pages of The Onion—albeit one that’s considerably less amusing because its subjects are real. So, when The Onion learned about the Sixth Circuit’s ruling in this case, it became justifiably concerned.

Its reasons are given in the spirit of the satiric publication:

First, the obvious: The Onion’s business model was threatened. This was only the latest occasion on which the absurdity of actual events managed to eclipse what The Onion’s staff could make up. Much more of this, and the front page of The Onion would be indistinguishable from The New York Times.

After that, however, the brief gets more serious. Governments having the power to punish those who make fun of them is a dangerous development, it asserts, adding that, in failing to defend parody, the court “imperils an ancient form of discourse.” What then follows is a smart explanation of how parody works. I won’t go into all of it, but key is that the parodist can’t signal parody ahead of time. To do so is to spoil the joke:

The court’s decision suggests that parodists are in the clear only if they pop the balloon in advance by warning their audience that their parody is not true. But some forms of comedy don’t work unless the comedian is able to tell the joke with a straight face. Parody is the quintessential example. Parodists intentionally inhabit the rhetorical form of their target in order to exaggerate or implode it—and by doing so demonstrate the target’s illogic or absurdity.

“Parody functions by tricking people into thinking that it is real,” the brief explains. When readers “realize that they’ve fallen victim to one of the oldest tricks in the history of rhetoric,” they can then “laugh at their own gullibility.” For parody to announce itself as parody, therefore, strips it of “the very thing that makes it function.”

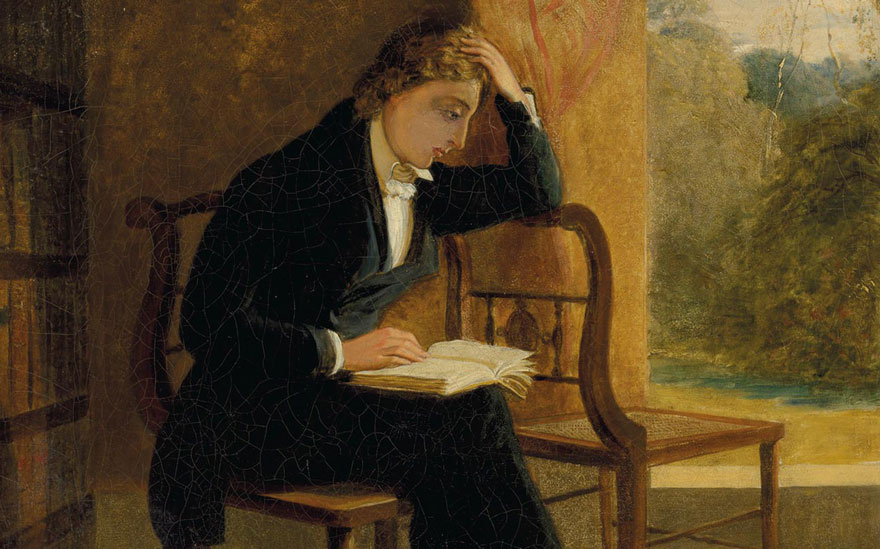

For an example, the brief goes on to cite the greatest parody ever written, although it does so in characteristic Onion fashion:

Assume that you are reading what appears to be a boring economics paper about the Irish overpopulation crisis of the eighteenth century, and yet, strangely enough, it seems to advocate for solving the dilemma by cooking and eating babies. That seems a bit cruel—until you realize that you in fact are reading “A Modest Proposal.” To be clear, The Onion is not trying to compare itself to Jonathan Swift; its writers are far more talented, and their output will be read long after that hack Swift’s has been lost to the sands of time. Still, The Onion and its writers share with Swift the common goal of replicating a form precisely in order to critique it from within.

As an aside, I’ll note that, when the publisher of Onion came to my college to speak, I asked him if Swift was a model for him and he essentially replied that Swift was the model. Regularly on this blog, usually on April 1, I’ve explored various Swiftian parodies, including “Meditation on a Broomstick,”

“The Last Speech and Dying Words of Ebenezer Elliston,”

and “Predictions for the Year 1708” (where he takes apart a noted astrologer by predicting his death—and then, in a follow-up essay, proving that, despite the man’s assertions to the contrary, he really did die on the date predicted). Gulliver’s Travels too is filled with parody throughout, starting with a parody of travel genre.

But back to The Onion. If parody did not mimic a particular idiom “in order to heighten dissonance between form and content,” it argues, “then no one would use it. Everyone would simply draft straight, logical, uninspiring legal briefs instead.”

The brief then gets to the heart of how The Onion uses parody. By giving parodists the ability to mimic the voice of a serious authority, parody can

kneecap the authority from within. Parodists can take apart an authoritarian’s cult of personality, point out the rhetorical tricks that politicians use to mislead their constituents, and even undercut a government institution’s real-world attempts at propaganda.

It then cites two somewhat famous instances of authoritarian regimes who took Onion articles seriously:

In 2012, …The Onion proclaimed that Kim Jong-un was the sexiest man alive. China’s state-run news agency republished The Onion’s story as true alongside a slideshow of the dictator himself in all his glory. The Fars Iranian News Agency uncritically picked up and ran with The Onion’s headline “Gallup Poll: Rural Whites Prefer Ahmadinejad To Obama.”

And another example:

Republican Congressman John Fleming, who believed that he needed to warn his constituents of a dangerous escalation of the pro-choice movement after reading The Onion’s headline “Planned Parenthood Opens $8 Billion Abortionplex.”

The brief has one last important point to make: “A reasonable reader does not need a disclaimer to know that parody is parody.” It goes on to point out all the ways that reasonable readers would have recognized Novak’s facebook spoof to be parody:

But the lack of an explicit disclaimer makes no difference to whether a reasonable reader would discern that this speech was parody. Just to be clear, this was not a close call on the facts: Mr. Novak’s spoof Facebook posts advertised that the Parma Police Department was hosting a “pedophile reform event” in which successful participants could be removed from the sex offender registry and become honorary members of the department after completing puzzles and quizzes; that the department had discovered an experimental technique for abortions and would be providing them to teens for free in a police van; that the department was soliciting job applicants but that minorities were “strongly encourag[ed]” not to apply; and that the department was banning city residents from feeding homeless people in “an attempt to have the homeless population eventually leave our City due to starvation.”

And it then brings in another big hitter:

For millennia, this has been the rhythm of parody: The author convinces the readers that they’re reading the real thing, then pulls the rug out from under them with the joke. The heart of this form lies in that give and take between the serious setup and the ridiculous punchline. As Mark Twain put it, “The humorous story is told gravely; the teller does his best to conceal the fact that he even dimly suspects that there is anything funny about it.”

“You don’t want to be on the wrong side of Mark Twain, do you?” The Onion asks the court before darkly concluding,

The Onion intends to continue its socially valuable role bringing the disinfectant of sunlight into the halls of power….And it would vastly prefer that sunlight not to be measured out to its writers in 15-minute increments in an exercise yard.

Unfortunately, with the rising popularity of whacko conspiracy theories (like QAnon’s claims of Democrats as cannibalistic pedophiles), it sometimes seems that certain politicos are using The Onion to shape their political belief systems. Democracy relies on the idea that there are more reasonable people than crazies out there—an “educated citizenry,” in Thomas Jefferson’s worlds—and we must pray that such is the case.

It wasn’t the case with the Parma police department, unfortunately, but at least the jury ruled in Novak’s favor. So I guess that’s the good news.