Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Friday

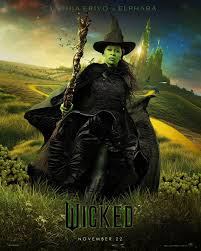

Julia and I attended Wicked early this week, and while I’m not a great fan of musicals, I was still entertained. The movie sent me back to the book, The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, which I once taught in a fantasy class and which is even darker and more disturbing.

As many have noted, the film is particularly timely given how we’ve just elected as president a man whose central election strategy is scapegoating vulnerable populations. In Wicked, it’s the Wizard of Oz who scapegoats, with one of his victims a literal goat (Dr. Dillamond). In Oz as in Narnia, there are talking and non-talking animals—“animals” and “Animals”—but the Wizard figures the best way to consolidate power in his rebellious country is to single out all animals.

In a science class attended by future witches Elphaba and Glinda, Dr. Dillamond reports on the Wizard’s new measures:

[T]he Wizard of Oz had proclaimed Banns on Animal Mobility, effective several weeks ago. This meant not only that Animals were restricted in their access to travel conveyances, lodgings, and public services to travel conveyances, lodgings, and public services. The Mobility it referred to was also professional. Any Animal coming of age was prohibited from working in the professions or the public sector. They were, effectively, to be herded back to the farmlands and wilds if they wanted to work for wages at all.

Dr. Dillamond, who has been researching genetic differences between Animals and humans and discovering that they are small and inconsequential, pays a price for his truth-seeking: the Wizard’s henchmen cut his throat. (As I say, the book is darker than the movie.)

In a scene that also shows up in the film, we see his replacement prepared to dissect a lion cub to determine whether it is animal or Animal. “This is a very young cub,” Elphaba objects from her desk. “Where is its mother? Why is it taken from its mother at such an early age? How even can it feed?”

As she learns more stories about such discrimination and abuse, Elphaba becomes a passionate Animal rights advocate. At first she lobbies the Wizard to retract the Bann and then joins a terrorist organization that seeks to assassinate him.

Of course, as a person of color Elphaba is also the subject of discrimination and scapegoating. (In the opening scene, we see the community celebrating her death.) It’s one reason she identifies so passionately with the persecuted Animals. But in her fight, she goes into some dark places, engages in some actions that backfire, and ends up being labeled evil and marginalized. By the end, she is so hollowed out and suicidal that she can’t recognize goodness when it finally shows up.

I’m not entirely clear what Maguire’s point is, other than perhaps an illustration of W. H. Auden’s observation that “Those to whom evil is done do evil in return.” Oh, and that people are more sympathetic once they are given backstories. In any event, when Dorothy shows up, asking for forgiveness and fully prepared to hand over the silver slippers, Elphaba is utterly confounded. Here’s Dorothy:

Would you ever forgive me for that accident, for the death of your sister; would you ever ever forgive me, for I could never forgive myself!

And Elphaba’s response:

The Witch shrieked, in panic, in disbelief. That even now the world should twist so, offending her once again: Elphaba, who had endured Sarima’s refusal to forgive, now begged by a gibbering child for the same mercy always denied her? How could you give such a thing out of your own hollowness?

She was caught, twisting, trying, full of will, but toward what?

In her confusion, Elphaba accidentally catches her dress on fire, leading to Dorothy’s frantic attempt to save her with the fatal bucket of water.

It’s an unsatisfying ending and, despite Maguire’s wonderful imagination, an unsatisfying novel. I’m not sure that it provides special insight into the nature of evil other than that good people, under relentless pounding, can become wicked, or at least very confused.

There’s one Elphaba insight, however, that may help us better understand Trump’s hold on his followers. For years I’ve had the fantasy that they would one day awake to see what a bad man he is and throw him off. But what if they are drawn to him because he’s bad.

What if they find evil entertaining because it gives them an illicit thrill to which they’ve now become addicted. Maybe they get a charge out of his grabbing women by the pussy and by his calls for cops to rough up suspects, for rally attendees to punch out protesters, and for the military to shoot demonstrators in the legs. Maybe a sadistic streak is activated when they hear about border agents tearing immigrant children from their parents or Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s razor wire tearing people as they attempt to cross the Rio Grande. For many people, watching angry voters swarming over the Capitol was the best television ever.

And when progressives, liberals, and traditional Republicans complain, that makes it all the more delicious. Trumpists love watching their leader make these “elites” squirm.

I got this insight into Trump’s popularity when Elphaba, at the time a student at Shiz University, is discussing the nature of evil with her roommate Glinda. Struck by Glinda’s observation about how boring preachers sometimes enliven their sermons by turning to evil, Elphaba finds interesting connections between

evil and boredom. Evil and ennui. Evil and the lack of stimulation. Evil and sluggish blood.

I first came across the idea that boredom can become toxic from an article by an 18th century British Lit scholar about the 1747 novel Clarissa. Samuel Richardson’s runaway hit features an angelic heroine whom her family loves to torment. I was baffled by all the ways they choose to punish her when she resists marrying an old, rich, ugly suitor until Frederick Karl suggested they are motivated by boredom. Messing with sweet, dutiful Clarissa adds variety to their otherwise empty lives.

The Marquis de Sade picked up on their sadism when he made Clarissa the model for his novel Justine, where for several hundred pages we watch the innocent heroine get tortured in multiple ways. Literally tortured, that is, not just browbeaten and locked in her room.

While surely not all of Trump’s supporters are stimulated by his sadism, I suspect a fair number are, including some of his so-called Christian supporters. Why settle for the boring competency of the Biden-Harris administration when you can get this instead?

A Reader’s Comment (Lory):

Yes, Maguire’s book is unsatisfying, and it’s unclear what the point is in the end — although it starts out with an impressive imaginative verve, it didn’t follow through for me. It’s interesting that the story has been given another life through the wildly popular stage version, though I also found that unsatisfying. Clearly something in it strikes a chord in the wider culture, and you bring out some of the themes and issues well.

I’ve lately become fascinated by the idea of the dysregulated nervous system, which most of us have to some degree. In me, it led to migraines and psycho-emotional disturbances, in others, it could lead to the “evil as a remedy for boredom” pattern. What you call boredom could be due to a shutdown or muffling of our healthy emotional life, a defensive strategy formed by childhood experiences. Trump’s childhood and family were certainly dysfunctional enough for that, and I have to wonder about the history of his followers — including some of my own loved ones.

They want a leader who hates what they hate, who gives them permission to cast out and destroy. But the scapegoat is not their real enemy, they’re too frightened to confront that, because it is within. What can give one the courage to make that turnaround and face the inner demons? I know what helped me, but not everyone has my opportunities and advantages. I can only keep wondering and praying for help in our affliction.

My response: This is very interesting, Lory. I feel confirmed in my own feelings of dissatisfaction but am even more interested in what you say about boredom. I reminds me a little of the theories of Alice Miller, who looked at the prevalence of emotional child abuse experienced by followers of Hitler. Facing up to one’s inner demons always strikes me as a vital step toward restoring inner balance.

Last night I participated in a discussion group applying the ideas of French philosopher René Girard to Wiked, focusing above all on his theory of scapegoating. The speaker looked especially at “No One Mourns the Wicked,” “What Is This Feeling?” and “Popular.” Of course, the songs don’t show up in the book. If I think of the book as an exploration of what happens to the psyche of one who has been scapegoated–and who doesn’t entirely have the inner strength to resist–it makes more sense. To the end, Elphaba is obsessed with the silver slippers, which her father gave to her sister. This sibling jealousy destroys her in the end.